My father’s birthday was November 1st. He died at 67, 30 years ago. But he has not faded in my heart and soul. He died of leukemia and lung cancer. He smoked a couple of packs of unfiltered Camels per day from 12 on. We’d stop on our long road trips so he could empty the ashtray. Like living under an airport flight path, we regarded cigarette smoke in the car, in the house, in a restaurant, and even on a plane as normal. When he was dying in our home in western North Dakota, one of his friends said, “Chuck, do you regret now that you smoked all of your life?” (Was this a friend or a purveyor of righteousness?) My father said, “I’ve enjoyed every cigarette I ever smoked, and I’m looking forward to as many more cigarettes as I will live to light up.”

My biggest regret is that my daughter Catherine did not get to know him. He would have adored her. They met once, but she was just 11 inches long.

He was born in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. His father died when he was 12. My sense (though he did not talk much about his life) is that my father morphed into Huck Finn at that point or Peck’s Bad Boy. He was a good high school basketball player in the last years of its set-shot era. His mother was often desperately poor. She took in boarders, all single men who didn’t need much more than a bed and a bathroom down the hall.

At war’s end, my father, now 18, joined the army. He was stationed at White Sands Missile Base in New Mexico. He said he had seen Wernher Von Braun there from time to time.

A Young Man With a Quick Mind From a Poor Family

He was a young man from a truly poor family with a high IQ and a very quick mind, who might have gotten stuck below the level of his talents had it not been for the G.I. Bill of Rights. He spoke of it as one of the noblest things the US government had ever done, the government grant that changed the trajectory of his life. He enrolled at Moorhead State Teacher’s College in Moorhead, Minnesota. He studied English, had a great mentor (a female African American scholar ALONE on the white-bread northern plains in 1951), dabbled with the poetry of the Beat Generation, wrote a somewhat off-the-shelf set of college literary magazine essays about the perils of the atomic age, drank pretty heavily and probably smoked a bit of reefer. He swept my mother off her feet. She was from a dairy farm in rural Minnesota, unfinished, a little awkward, and thinking about a career in the church. He used to joke, “If I hadn’t rescued her, she’d still be out there sloppin’ hogs.” To which my mother would say, “Oh, for dumb.” They eloped. She was probably pregnant. But they eloped and broke her parents’ hearts. The in-laws soon learned to prize the man they called “Charlie,” but they had a hard time getting over the elopement.

Two children. I’m the second. My sister Leslie Jo, two years older than I, died six years ago at 63. She smoked two packs of cigarettes every day of her adult life.

My father took a job with a national small loans company. He was stationed in western North Dakota. He was transferred from the lush lake country of northern Minnesota with its lifeline to Minneapolis, to the windswept shortgrass prairie of Stark County, N.D. No trees. Long raw winters. Fewer readers than one would hope. No man was ever less North Dakotan than he was. He led an entirely sedentary and interior life.

Some of My Best Conversations Were With My Father

My father was a great reader. If there could be only one tableau of him in my consciousness, it would without question be him sitting in his reading chair to the right of the couch, be-slippered with a hassock before him, and an inexpensive mosaic end table next to him for the cigarette pack, the ashtray, and the Walkers & Water highball he poured himself 53% of all the nights of his life. The television would be on across the way, a 20” color console set with no remote, and a standing lamp was adjusted for optimal reading light. The sound was turned down. He’d be reading the New Yorker or the Minneapolis Tribune in that chair or a book of nonfiction about the American political scene, particularly after Richard Nixon dragged the country into his darkness. He’d light up a cigarette, read for a while, take a sip or two of his drink, and light up another cigarette. At about 11, he would quietly excuse himself and go to bed.

He was exceptionally witty, well-spoken, and well-read, with just enough literary reference to be charming and not tedious. He was always carefully groomed. Immaculate fingernails. He was a man of small stature and lean. Slightly balding on the top. He had perfect penmanship. He was the best speller I ever knew. He kept a dictionary on the shelf next to his reading chair (which nobody else ever sat in twice, though he protested that it was not his chair), and he’d look up from his reading and say, “Let’s look up the word ‘tergiversation,’ shall we?” And we did. Occasionally, in my youthful naivete, I thought I was right and he was wrong about how a word was spelled or pronounced, and we’d bet some small amount. He was always right, not in the sense of usually but always. It got annoying. Once, I gave a lecture in a neighboring town, and afterward, random people came up to tell me how good I was. My father waited until a lull, walked up, and said only, “It’s pay-tent-ly, not pat-ent-ly.” And walked away. And I was not even slightly offended.

He didn’t read much fiction after his early 30s, but it is clear that he had read an enormous amount of the literary and historical canon in his university and Beat years. I’d say something about Dostoevsky, and he’d say, “You know, I haven’t read Crime and Punishment since I was in college, but I think Raskolnikov’s encounter with the inspector in the pub is wonderfully written. We can only imagine what it would be to read it in Russian.” Or Dante, or Milton, or Shakespeare, or Henry Fielding, or Orwell, or T.S. Eliot, or Chaucer …

Some of the best conversations I have ever had were with my father. We read Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Star (about the Custer fight) together. We went to Hardee’s restaurant four days in a row. We took our sandwiches to an empty park so we could compare notes, talk the issues, point to our favorite passages, and consider the conquest of North America and its consequences. This from a moral, social, political, and environmental point of view. He was always reading The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich for the fifth or seventh time.

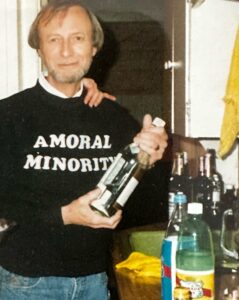

He was grammatical. He had a vast vocabulary, which he did not use much in public, but if I asked him about a word, he almost invariably knew it. He was never vulgar. I never said the F-word in his presence in my life, and I think I blurted out shit only once or twice. He would not have objected or rebuked, but he might have turned away and gone back to his reading. He would not let a racist joke be told in his presence. When it happened, and it happened quite a bit in North Dakota cattle country, he would quietly get up and leave the room without making that a statement. He used to send me dozens of short typewritten notes on quarter sheets of paper. By now, he was a banker in our town, a small loans officer, and later the bank’s compliance officer, and he used his spare time on the job to type me a weekly “terse note,” as I called them. I still have some of them. He was easily amused, but he seldom laughed out loud. His sense of humor was a little eccentric. Two examples. When the Moral Majority was at its height, he had a sweatshirt made up at the modest little mall that said AMORAL MINORITY, which he thought was infinitely clever. When one of his friends served on the local water board, he had a plaque made with an outdoor faucet attached and the letters BIGGEST DRIP AWARD — that sort of thing.

There have been times when I have wondered if I would have been happier with a more typical heartland father. My father would not camp, hike, picnic, play catch in the backyard, fish, hunt, or even shoot, and he drove onto off-pavement gravel only if there was no way it could be avoided. He had many phobias. He panicked when we drove across a high bridge or along a mountain road. Once at Hannibal, Missouri, when they were taking me to college, we crossed the Mississippi on a very long and high bridge. We were there because my mother insisted on that literary pilgrimage. My father made me stop the car. He got in the back seat and pulled a blanket over his head. But we survived.

I know this much. He would have regarded my plan to traipse around the country in an Airstream as purely moronic, but he would have been the first to ask perfect questions about it when I came up for air.

When I enrolled at the University of Minnesota, he said he would cover my tuition bills on one condition: I must take a course from the legendary Mulford Q. Sibley, a quintessential midwestern liberal who had questioned our mission in Vietnam before most Americans had heard of such a place. I complied. Sibley was one of the great intellectual pleasures of my life.

What if my father had been an outdoorsman who was eager to initiate me into the rights of rural manhood? What if he had wanted to hike the badlands with me or take me on Canadian fishing trips? I live in a state where that is the norm. And I know many people my age who grew up in that universe who seem to thrive in this world and don’t try to read five hours per day and write books and lecture about a gazillion things. Would I have been happier if I had grown up closer to the Great Plains norm? Would I sleep better? I know this: whenever I achieve something, no matter what it is, the person I want to call is my father.

Two Roads Diverged

Two roads diverged. I took this one because my parents were teachers and readers. I camp and hike and do canoe and raft trips and climb high peaks, and occasionally do mega-hikes of several week’s duration. But I wish I could weld and make an exquisite reading desk of aromatic woods and build a deck on the west side of my house.

My father was a McGovern Democrat in a state where McGovern got only 35% of the vote in 1972. He was quietly (at the Elks Club and the Shamrock Bar) outspoken in his criticism of our Vietnam policy. He spoke his mind on the golf course and at cocktail parties, which were common in that era. But even his right-wing friends approved of him and listened to his arguments. They thought he was nuts, but they appreciated his civility and bemusement. He was stricken by the Kent State killings. We ordered James Michener’s Kent State: What Happened and Why, read it simultaneously, and had long, marvelous conversations about dissent, social responsibility, accountability, the dangers of a security state, and the gravity of our moment in American history.

If he had not been what he was, a Depression child obsessed with financial security, he might have been a writer or a university professor. He did a great deal of research and a good deal of writing and lecturing about the Diary of Samuel Pepys and the Journals of James Boswell. I turned him on to these diarists while I was studying at Oxford. By the time I got home to North Dakota, he had acquired a couple of dozen books on each of them, including, of course, their complete works. On these subjects, he tended to wax a little obsessively, and his friends on Friday nights at the Elks either excused themselves or ordered doubles.

Would I have wanted it any other way?

No.

I can ache for those things a little without forgetting what he gave me. I have lived my life in books, written some, planned more, midwifed a few, and collected several tens of thousands. Aside from my daughter, there is nothing I would less rather have taken from me than the humanities. I hike and camp and seek strenuous adventures (my father regarded them all as pointless retrogression), and I am not afraid of much, indeed not heights, but I wish I knew how to weld or change out the rings of a 1957 I-H pickup. I get to read about half the day. It hasn’t quite paralyzed me.

We’d have a special secret family meal tonight if my father were here, and I’d pour myself a lite Walkers & Water with him. I’d almost certainly throw him a bogus spelling gambit to see him, with a wry, somewhat self-satisfied smile, reach over for his beloved American Heritage Dictionary.

He and my daughter would have been co-conspirators in life.