The recent record-setting auction of a $32,000 Spanish cheese brings to mind the curious tale of Thomas Jefferson’s 1,235-pound Mammoth Cheese.

I read recently that a Spanish cabrales blue cheese has sold at auction for more than $32,000. The 4.8 pound wheel was created by Guillermo Pendás at a family factory in Los Puertos. It was aged in a mountain cave at Asturias in northern Spain. The cheese was named best Cabrales cheese at Las Arenas’ 51st annual cheese competition.

Diamonds are forever, but a cheese is classified among the perishables. Under the right circumstances you can age certain cheeses a long time, but at some point, its only value is in eating it. That’s $32,000 down the … let’s say drain. The award-winning cheese was purchased by Iván Suárez, the owner of the Llagar de Colloto restaurant near Oviedo (northern Spain).

I’ve had some very fine cheeses on a barge on the Canal du Midi in southern France, and of course I deplore American cheeses, along with American bread, American olives, and other things (like tomatoes) that we manipulate for long shelf life rather than deliciousness. I’ve made some goat cheese in my day, back when I was a western Kansas goat farmer — perhaps hobby farmer would be more precise. My friend Patti Perry was a sadist. She gave my wife and me two dairy goats for a wedding gift and a cheese press. Here’s an insight about keeping dairy animals. They just keep producing milk! On the first day we had two quarts of milk. By the third day the accumulated total was two gallons. By a month later we were drowning in goat milk. We could not sell it. We gave it away to anyone who would take it. We spent a lot of time convincing new parents that their children were probably cow-milk intolerant. We fed pigs. We made yogurt. But within a short time, we were drowning in goat milk. We finally just left the state.

Meanwhile Back at Thomas Jefferson’s White House

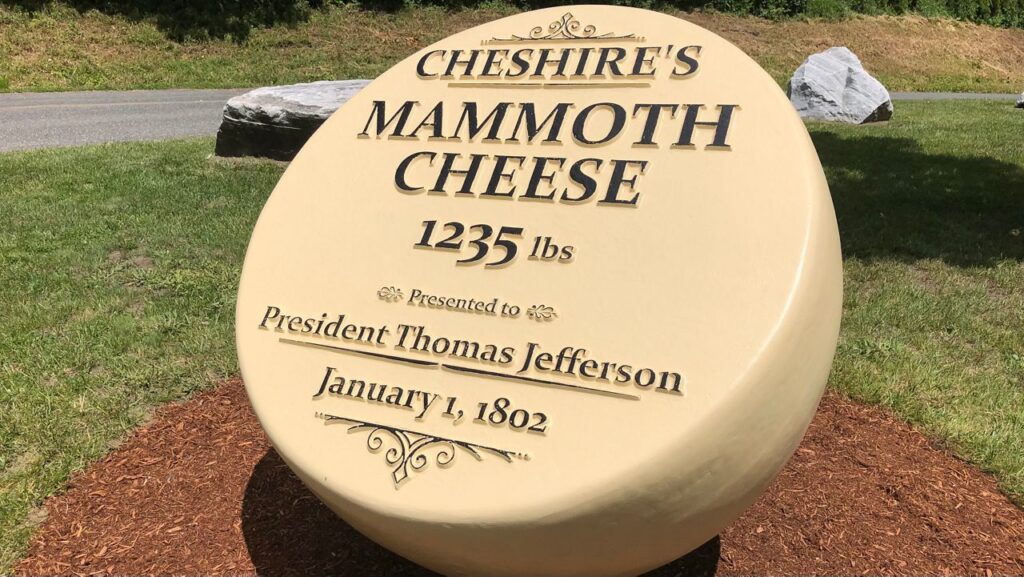

The prize Spanish cheese reminds me of Thomas Jefferson’s mammoth cheese. To celebrate Jefferson’s doctrine of separation of church and state, an enlightened reverend named John Leland of the Cheshire Baptist Church in Cheshire, Massachusetts, organized local farmers to donate milk to produce a massive cheese for the third President. The 1,235-pound cheese was delivered “in a wagon drawn by six horses” to the White House on January 1, 1802. Leland claimed that 900 cows — none of them Federalist cows — had contributed to the cheese, which had a diameter of 4 feet and a depth of 15 inches. Affixed to it was Jefferson’s motto: “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”

The cheese was so heavy and so large that the logistics of transporting it from Massachusetts to the District of Columbia (386 miles by land, more by water) represented a heavier burden than the cheese itself. Cheshire had to hire a sleigh to get it to a barge on the Hudson River. After floating down the Hudson to New York City, the cheese was loaded onto a sloop en route to Baltimore. At Baltimore it was loaded onto a stout wagon for the last leg of its epic journey.

There is even a Paul Revere in this story. The teamster who delivered the cheese to Washington, D.C., hastened to the White House ahead of the gift to warn Mr. Jefferson. When he was shown into the President, he said, “Say, there’s a whopping big cheese come from Cheshire. Knowing it might be a surprise I came to prepare you.” When Jefferson asked his name, the teamster replied, “Fredrick Dunham at your service. I brought down the cheese myself. No small job but I did it. It’s a likely cheese and brought by a likely man, if I do say so.” Jefferson was charmed.

The Reverend Leland delivered a short address at the White House on New Year’s Day, under the title, “The Greatest Cheese in America for the Greatest Man in America.” During his visit, Leland also delivered a sermon in the nation’s capital, which President Jefferson attended. Reverend Leland’s Biblical text was from Matthew 12:42, “And behold a greater than Solomon is here.” This was laying it on a little thick, the kind of praise that made Federalists gag.

Once the ceremonials were over, there was nothing left to do but sample the cheese. Here is an eyewitness report:

“The steward of the White House then, on a signal from the president, advanced with a huge and glittering knife and carved the monster cheese in the presence of the president and cabinet, foreign diplomats and many distinguished men and women of ancient note. Its color was a beautiful annotto [sic, an orange-red], somewhat variegated in shade owing to the mixture of so many different curds, and it was the object of the greatest curiosity. Great slices were served up with bread to the president, cabinet, diplomatic representatives in the order of their rank and station, and to others, until all had been feasted.”

Jefferson’s detractors regarded him as a bubble-headed crackpot and particularly ridiculed his fascination with the mastodon and the woolly mammoth (that era’s “dinosaurs”). They immediately began to call it the Mammoth Cheese. In fact, historians of the English language say that this was the first time “mammoth” was used as an adjective.

Reverend Leland was an abolitionist. In the accompanying letter to the slave-holding president, the people of Cheshire declared that “the cheese was procured by the personal labor of freeborn farmers with the voluntary and cheerful aid of their wives and daughters, without the assistance of a single slave.” Ouch. Probably Jefferson would have said he agreed with both the sentiment and the implied criticism. He would have written one of his characteristic “Nobody wishes more than I …” letters about the eventual eradication of slavery from American life. But not quite yet.

Jefferson was a true small-r republican. Not wishing to accept gifts from the American people or others to avoid even the slightest appearance of conflict of interest, Jefferson promptly sent the people of Cheshire a cheque for $200. That comes to more than $4,000 today. No wonder Jefferson died bankrupt.

Reports on the quality of the cheese vary. As you might expect, Jefferson’s Republicans pronounced it delicious, and the Federalists declared that it was inedible. When your goal is size not quality, you are probably not going to win any culinary awards. The record is a little uncertain about how long the cheese occupied the White House. One report has it still “aging” as late as New Year’s Day 1805. Other accounts confirm that it was still being served at public occasions as late as 1803. One report says that a large chunk (if that is the correct technical term) was presented to Congress in March 1804. I’ve read accounts of members of Congress coming to dine with Jefferson quietly asking his aides if they could be ushered in to see the famous cheese. Although White House staff dutifully and repeatedly discarded the rancid outside parts of the decaying cheese, thus seriously reducing its enormous bulk, some of it was eventually dumped into the Potomac.

The Federalists had a field day with the whole incident. A Mammoth Cheese in the Mammoth Room (i.e., East Room) of the White House for the Mammoth President, who believed that the Woolly Mammoth might still be grazing on the Serengeti of Montana. Jefferson’s blank vocabulary grid that he sent with Meriwether Lewis in 1804 includes the word Mammoth, in the hopes that Lewis would encounter a tribe that had a living memory of the great quadruped.

After the New Year’s Day festival of 1802, one Federalist newspaper wrote:

“No circumstance which has attended the Mammoth Cheese is so strange and ridiculous, as the sending it under the convoy of John Leland, a clergyman of the Baptist persuasion. He was probably the penman too of the wonderful address to the President on the presentation of the Cheese. That a minister of the gospel should leave the duties of his office, travel several hundred miles, undergo ‘perils of waters, perils of robbers, and perils in the city,’ merely to guard a cheese, one knows not whether to laugh at the sight, or be filled with indignation at the prostitution of his profession. One would think that his brains were either made of curds, or that they had become maggots. … A man who can so far depart from the propriety and dignity of the ministerial character, ought to be divested of it, and suffered to follow that to which his talents seem to have a fitter, and his inclination leads him, the business of a CHEESEMONGER.”

So, on the political front, nothing has changed since 1802!