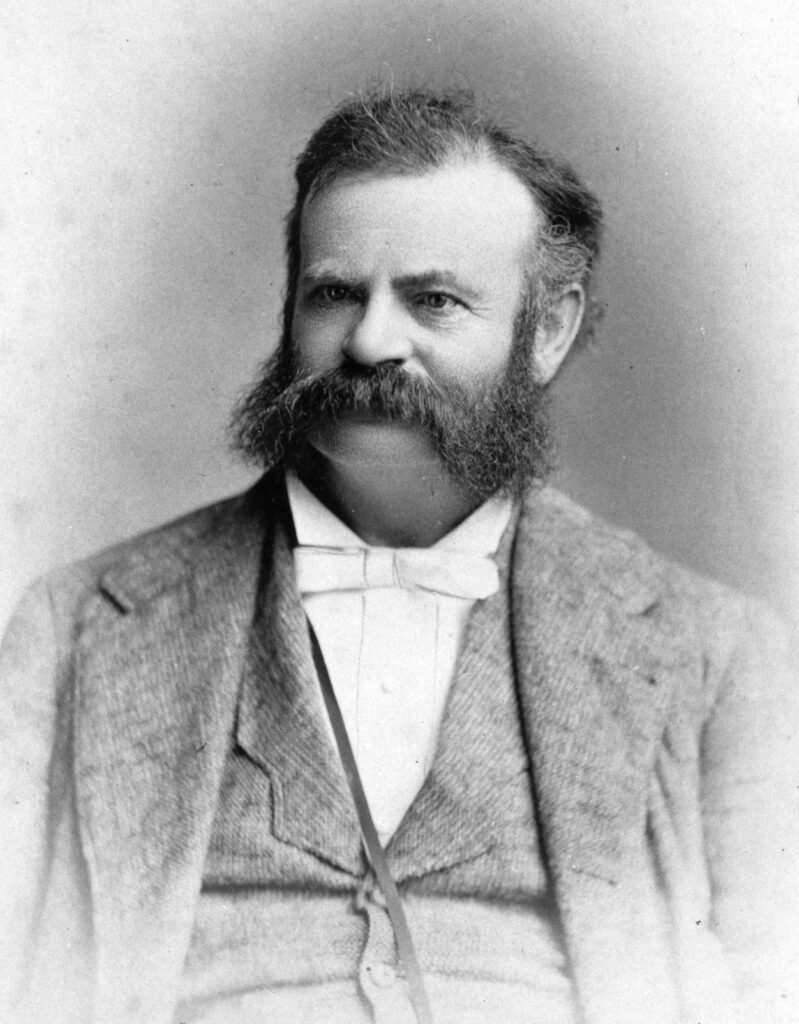

A recent journey following the Colorado River has Clay and his colleagues tracing a trail first mapped by the great American explorer and scientist John Wesley Powell between 1869 and 1875.

This article is part of series on Water in the West, chronicling a trip Clay Jenkinson and two colleagues took through Colorado River country in the spring of 2023.

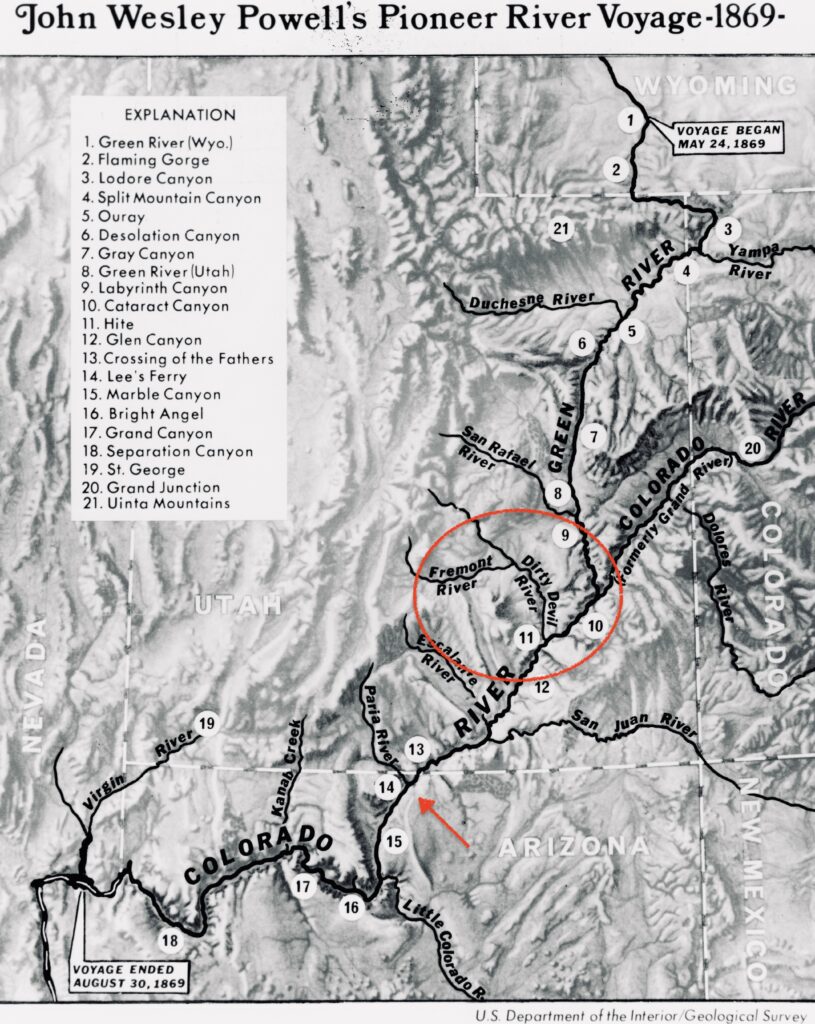

John Wesley Powell and his crew of eight arrived at the mouth of Dirty Devil Creek on July 28, 1869, 65 days into their 100-day journey down the Green and Colorado Rivers. They had just worked their way through the treacherous Cataract Canyon. It had been a harrowing experience. The pilot boat, the Emma Dean had swamped, lost three oars. All three of the remaining boats were beginning to disintegrate from the incessant battering of the river. Near the mouth of Dirty Devil Creek, they stopped to caulk the boats and make new oars.

From the plateau above, we look down on the deserted marina at Hite. If you are trying to illustrate the disastrous drop in Lake Powell over the last quarter century, this is one of the prime photo sites. Here, at the tail end of Lake Powell, the Colorado has completely receded to its traditional riverbed, a couple of hundred yards from the lowest concrete slab of the marina. You can see the outline of where the lake once was because the “footprint” is marked by dead foliage. The gray flats signify what was once the upper end of Lake Powell. The abandoned bottoms are gray and ugly. Hite is deserted. The motto of the marina might be “abandon all hope ye who enter here.”

The Dirty Devil is barely visible from up on the cliff. Our eyes are riveted to the deserted marina.

The Dirty Devil River is only 80 miles long. It is formed near Hanksville, Utah where we stopped for gas and drinks, by the confluence of the Fremont River and Muddy Creek. The canyon through which it flows is often 2,000 feet deep. The river’s average flow is 446 cfs.

Jack Sumner, who was essentially second in command of the Powell Expedition, wrote, “The water is about as filthy as the washing from the sewers of some large, dirty city.” The stream “stinks bad enough to be the sewer from Sodom and Gomorrah, or even hell. I thought I had smelt some pretty bad odors on the battlefield two days after action, but they were not up to the standard of that miserable little stream.” Most of the men of the Powell expedition were veterans of the Civil War. That’s one reason they were drifters in the American West, one reason why Powell was able to recruit them on short notice to undertake the dangerous adventure. Here is Powell’s explanation for the naming of the Dirty Devil. “One of the men in the boat following, seeing what we have done, shouts to Dunn and asks whether it is a trout stream. Dunn replies, much disgusted, that it is ‘a dirty devil,’ and by this name the river is to be known hereafter.”

Thus, Powell named the tributary almost certainly because the river stank. But later, long after the mutiny at Separation Rapids, Billy Hawkins and Jack Sumner hinted that Powell had named the river as a deliberate insult to Bill Dunn, one of the three “deserters.” Wallace Stegner, in his excellent book Beyond the Hundredth Meridian thinks this is unlikely. The river stank like dead bodies on Civil War battlefields. End of story.

It is true that by this point in the journey, tempers were beginning to flare. The spirit of the group was beginning to fray. George Bradley wrote that Powell gave the river the name Dirty Devil “in keeping with his whole character which needs only a short study to be read like a book.” It’s not clear what this means, but the tone of derision and contempt is clear enough. Here’s my best analysis of what was happening to the esprit de corps of the expedition at the end of July. Their food supply was running short. What food there was — flour, bacon, coffee, dried apples — was in poor shape from countless dunkings in the river. Their clothes were now not much more than rags. Powell was annoying. At every stop he wanted to go off “geologizing,” and he often suspended travel at midday in pursuit of science. In the eyes of the other men, there was no longer time for arbitrary stoppages. They were racing against the clock. Science was a luxury they could no longer afford. Nobody knew how far they were from their final destination. This is the biggest challenge of exploration and is hardest for us to understand 153 years later: they had no idea what challenges they still had to face or how far they were from the end. We know they hadn’t even entered the Grand Canyon yet — the real ordeal was yet to come. There was tension in the ranks. Powell blamed William Dunn for the disaster at Disaster Falls, which destroyed one of their boats and swept a third of their gear down river. He also blamed Dunn for losing maps and documents along the way. Everyone just wanted to be done with the journey. They were all bewildered and frightened, even Powell. He called the deepening canyons “our prison.”

Here at the mouth of the Dirty Devil, however, expedition members managed to kill two bighorn sheep — a very rare and welcome manna of fresh meat. Powell writes: “We lash our prizes [the sheep carcasses] to the deck of one of the boats and go on for a short distance; but fresh meat is too tempting for us, and we stop early to have a feast. And a feast it is! Two fine young sheep! We care not for bread or beans or dried apples tonight; coffee and mutton are all we ask.”

On our recent journey to the area we didn’t give much time to the Dirty Devil. We gave more time a few days later to the Paria River. The Paria slides its tan chocolate contents into the Colorado at Lee’s Ferry, which did not exist in Powell’s time, though Powell knew Jacob Hamblin (the Mormon frontiersman), who found the crossing for his theocratic boss Brigham Young.

The Powell Expedition reached the Paria on August 4, 1869. Powell seems to have missed the confluence during the trip itself, but he had figured things out by the time he wrote his Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons in 1875. The Paria’s sludgy silt load winds up in the Colorado as does the silt load of the Little Colorado. The rest of the Colorado’s tributaries drop their silt in the backwaters of the reservoirs at Flaming George and Glen Canyon.

We got out of the truck and fanned out, each of us looking for a good photograph of the confluence, which exhibits the contrast between a typical lower-Colorado tributary and the clear, silt-filtered waters of today’s Colorado River. What struck me most there, however, were the cottonwood trees. They were just beginning to leaf out on the shores of the Colorado. They had that lemony, almost translucently green look of early cottonwood leaves. The sun seemed to cast a golden green aura over the little copse. Cottonwood leaves are at their most beautiful in the first and last weeks of their annual life. This was our first glimpse of the spring that is coming to the southwest. But I couldn’t get a photograph that even began to do justice to the delicacy and the subtlety of these trees. Most of the best things in life are beyond photography, and yet we’d give anything to have photographs of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the first Powell Expedition, the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

For several decades I’ve been told that the Paria canyon is one of the great hikes in America. I don’t doubt it, but I’m guessing there are several hundred, perhaps several thousand, outstanding hikes in southern Utah. The Paria is only 95 miles long. Buckskin Gulch is considered one of the premier slot canyons in the West.

There are two extremely important truths about Powell’s 1869 descent of the Green and the Colorado. First, they could not know what was ahead. They had been shaken enough and frightened enough during the journey so far that a significant level of gnawing apprehension was a constant factor. Powell would later say, “only during the few hours of deep sleep, consequent on hard labor, has the roar of the waters been hushed.” Second, and perhaps more important, by the time they arrived at the gateway of the Grand Canyon, even by the time they arrived at the mouth of the Paria, they were spent. They were nearly naked. They were eating slender rations of unleavened biscuits, rancid bacon, coffee, and some dried apples. They were beginning to lose some muscle mass. They were physically just worn out. They were out of mojo — they were spiritually spent, and their hearts were no longer in the journey. It’s not clear how many of the nine would have pressed the button if in doing so they could be airlifted out of the canyon to a splendid meal above, no shame attached, but it is at least three of the crew and maybe as many as six. They did not know how many more rapids were before them, and how dramatic they were likely to be. If they had been able to exit the river for a few weeks, get some new supplies, including fresh clothing, rest their weary bones and recover their equanimity, and come back refreshed at the portal of the Grand Canyon, all that followed might have been different, better, less harrowing. They began their transit of the Grand Canyon when they had run out of everything that mattered, including the exhilaration of exploration. That’s no way to float the Grand Canyon.

John Wesley Powell and Glen Canyon Dam

People are always asking me two questions about John Wesley Powell. What would he have thought of Glen Canyon Dam? And how would he feel about the reservoir that drowned Glen Canyon, including the Music Temple? I don’t know the answer to these questions. Like everything else, it’s complicated. Powell was a utilitarian. He essentially believed that any cubic inch of water that reaches the ocean has been wasted. At the least, he wanted to divert as much volume of the western rivers as possible up onto irrigated landscapes in the immediate watershed. The greatest good for the greatest number seems to spell Glen Canyon Dam. In his subsequent work for the U.S. Geological Survey, Powell “located” more than 200 good dam sites in the American West, several in the lower Colorado canyons. I’d like to believe that Powell would prefer the old Glen Canyon to the new reservoir. That seems to square with his canyon country aesthetics. But you cannot be sure on that one. If pressed, I’d admit that I believe Powell would have been in favor of Glen Canyon and Hoover dam, but with some serious caveats. He wanted dams to be low — say maxing out at 50 feet not 700! Second, he did not like the implications of industrial gigantism. He didn’t want capitalism to build the dams and he didn’t like the idea of big government. What he envisioned — surely quaint by today’s assumptions — were local cooperatives that would build the dams themselves. “I say to the government, hands off!” he wrote.

Like so many others of his generation, he wanted to make the desert bloom. It is Thoreau who says, “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone.” But Thoreau is the outlier, Powell an advocate for transforming nature to serve human needs.

“A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone.”

Henry David Thoreau

But would Powell be pleased that the lake was named for him? I think almost certainly not. Powell preferred not to name things in the southwest after his colleagues and friends and heroes. His preferred method of naming was descriptive, and he was very good at it: Flaming Gorge, Beehive Point, Marble Canyon, Desolation, Labyrinth, Cataract, and Glen. “Glen” is one of the last words one would think to designate anything in desert country, but it turns out to be a nearly perfect name. Or rather it was. Glen Canyon is gone. And everybody we talked to on our journey, across the political spectrum, agreed: it ain’t never comin’ down. Glen Canyon makes sense, Glen Lake not. At this point, it’s hard to think of the place as anything but Lake Powell. Given the assassination of JFK in November 1963, when the dam was just high enough to begin impounding water, it’s a little surprising that it did not wind up as Lake Kennedy. That would have been wildly inappropriate. Whatever else he was, John F. Kennedy was not an outdoor adventurer. Try to imagine Kennedy camping with Edward Abbey, the way Theodore Roosevelt camped with John Muir in Yosemite for three nights. Just try. “This is moh vigah than I had in mind, Ed.”

Powell’s adventures on the Colorado River served as the launching point for a brilliant thirty-year career as a government scientist, a land and water reformer, and a visionary. He gave the middle decades of his life to ethnology (he knew half a dozen Native languages, mostly of the Great Basin); to geology (he added materially to the science and the nomenclature); to cartography (today’s USGS maps use his conventions); to the study and taxonomy of Native languages; to the establishment of proper management practices for the arid lands; to relations between ethnologists and native people (he refused to travel with a military escort).

In 1878 Powell published his Arid Lands Report, one of the most important (and ignored) documents in the history of the lands beyond the hundredth meridian. Among other things, he called for prior classification of all remaining western lands before they were deeded out. This was to prevent individuals or corporations from buying up key dam and canal sites and then monopolizing the distribution of water in their districts. But it was also to prevent innocent homesteaders from failing — or worse — on lands that could not support a family farm. He said irrigation farms should be limited to 80 acres of the public domain, but pasturage farms (i.e., ranches) should have a minimum of 2,560 acres (four sections). He furthermore wanted every homestead in arid country to have access to a watercourse that could at least water 20 acres. Powell advocated the creation of local grazing associations to self-police ranch management and local irrigation associations to supervise the distribution and use of water.

Perhaps most important, he argued that we should abandon Jefferson’s checkerboard cadastral survey grid system in favor of a more sinuous approach to land distribution, based on the long lot system used in French Canada, and he urged the U.S. government to consider forming holistic basin republics rather than the blockish rectangular states that Jefferson preferred. Only if an entire watershed or key portion of that watershed was under a single jurisdiction would incessant litigation and water wars be avoided. He called his proposed states watershed commonwealths.

It’s worth taking the time to read the Arid Lands Report carefully. Had we listened to Major Powell, we might have developed the lands beyond the hundredth meridian more responsibly.

But we did not listen.

Powell’s key insights about water scarcity in the American West are as important now as they were then, but in the century and a half since he explored the West, we have attempted to defy nature and the carrying capacity of America’s semi-arid and arid lands, and baked in just the sort of water crises he gave his life to prevent. Powell said:

-two fifths of continental USA is too arid for normal dryland agriculture;

-the 100th Meridian is the line of demarcation between lands that can support traditional agriculture and those that must be supported by irrigation;

-if we diverted all the available water in the American West, you would be able to irrigate no more than 3-12% of the land;

-if you don’t pre-classify these lands before turning white people loose on them, you are inviting endless trouble.

John Wesley Powell was a scientist and a realist. His idealism was tempered by an unblinking dedication to data, to the facts, to the limits of what humans can bring about by way of engineering.

If Powell Returned Today

If Powell returned today, what would he see? He was at heart a Jeffersonian, by which we mean that he wanted the West to be the home and haven of average American farmer citizens. I think Powell would marvel at our water works — the beauty and power of the great dams; the endless concrete canals and delivery systems as far away as Phoenix and Tucson and Los Angeles; center pivot irrigation, now with water conserving drop nozzles; the growth and size of the great cities of the southwest; air conditioning; rafts so stable that it’s difficult to flip one. I think, however, Powell would be alarmed at the ways in which the West has become a playground for the super-rich, the ways the reclamation laws have been corrupted to support giant corporate farms, and the locking up of some of the most beautiful landscapes by the most privileged Americans, people who visit their second or third or fourth homes for perhaps three weeks per year but fence the rest of us out. Powell would certainly be alarmed by the over-allocation of western waters, particularly the Colorado. And, as a scientist, he would want to get up to speed as rapidly as possible on the data about global climate change and its ramifications.

Powell came from the baseline of the American social structure. He was what Hamlin Garland called a son of the Middle Border. In the decades following his famous adventure, he became the most powerful scientist in the United States. He was at the same time the director of the US Bureau of Ethnology (from 1871), the director of the US Geological Survey (from 1883), one of the founders of the Cosmos Club and one of the founders of the National Geographic Society. For a short period, he was the water czar of the United States. But he never forgot his roots in the world of midwestern homesteads. His vision was to remake the arid West into a landscape that could support countless families just like his own. He was not an agent for the rich, for the special interests, for the most privileged sectors of the American social system. He grudgingly located potential mineral extraction sites in his surveys of the West, but he never emphasized mining, because it wasn’t Jeffersonian.

Post script: Late in his career, Powell gave a speech at an irrigation conference in Los Angeles, California. His remarks, unpopular and heckled at the time, still haunt us in 2023 —

“When all the rivers are used, when all the creeks in the ravines, when all the brooks, when all the springs are used, when all the reservoirs along the streams are used, when all the canyon waters are taken up, when all the artesian waters are taken up, when all the wells are sunk or dug that can be dug, there is still not sufficient water to irrigate all this arid region. [Crowd boos] What matters it whether I am popular or unpopular? I tell you, gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply these lands.”

John Wesley Powell, Los Angeles, California 1893

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water In the West.”

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.