Attending a magic show by my friend Joshua Jay in Pittsburgh got me pondering the “magic” of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Today, Friday, May 23, 2025, I attended a magic show in the theater district of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My friend Joshua Jay had invited me to see his new show and arranged a second-row seat for me in the Liberty Magic Theater. Joshua Jay is one of the top five sleight-of-hand magicians in the country — in the world.

Sitting at the dinette desk in my Airstream, planning my day, I had a brief flush of guilt. On a journey following the Lewis and Clark expedition across the continent, why was I taking time to see a magic show?

Note: I went to the theater at the appropriate time. The show was outstanding. Josh first made my guilt disappear, and later, at a Greek restaurant, the check!

As I brooded about my lack of focus, I realized Lewis and Clark had their own magic show. First, some background:

Lewis and Clark crossed the continent with an outstanding crew — 33 in the permanent party. They carried pork and flour and lard in kegs and a considerable (but in the end, inadequate) supply of whiskey, but they knew from the beginning that they would mostly be living off the land. Most of the men were proficient hunters, several outstanding, including Lewis. Captain Lewis ensured they had state-of-the-art Harpers Ferry 1803 rifles and a vast amount of powder and ammunition.

In 28 months across a vast continent without a single convenience store, they killed and ate a gazillion deer, hundreds of buffalo, scores of elk, a handful of bighorn sheep, and several hundred fish, and they wantonly killed every grizzly bear they encountered merely because they regarded them as a potentially lethal nuisance.

There were times, however, when they depended on Native Americans for food, principally during the winter at Fort Mandan in today’s North Dakota and during the return up the Columbia and Snake rivers in 1806. They traded for food (corn and squashes from the Mandan, dogs from the Columbians) with what we would call trinkets and gewgaws (tiny mirrors, fishhooks, curtain rings, beads, scarves, and spare bits of sheet iron). Unfortunately, by the time the expedition returned from the Pacific Coast on March 23, 1806, the Corps of Discovery was essentially bankrupt. Clark said all they had to trade — to get across the continent! — could be contained in two handkerchiefs. Try crossing America without money sometime!

At this point, the captains resorted to some “magic” to obtain the food, firewood, canoes, horses, and guiding services they needed to get home.

The Noiseless Gun

From the very beginning, they used their magic air gun to impress (perhaps overawe is a more accurate term) the Natives and secure their cooperation. As he scurried about back east in 1803, provisioning the great expedition, Meriwether Lewis had purchased an air gun in Philadelphia, probably from a craftsman named Isaiah Lukens. You could pump air into an airtight receptacle and fire up to 40 noiseless (fhhtt!) shots before repumping. It’s not clear why Lewis purchased the gun. Perhaps he thought it could prove helpful if, for some reason, the expedition lost or ran out of its gunpowder supply. Probably, he regarded it as an interesting novelty. And it probably seemed clear, as it soon proved, that the air gun would fascinate the Natives they met, who were still making sense of the gunpowder muskets and rifles that white people had brought to the American interior.

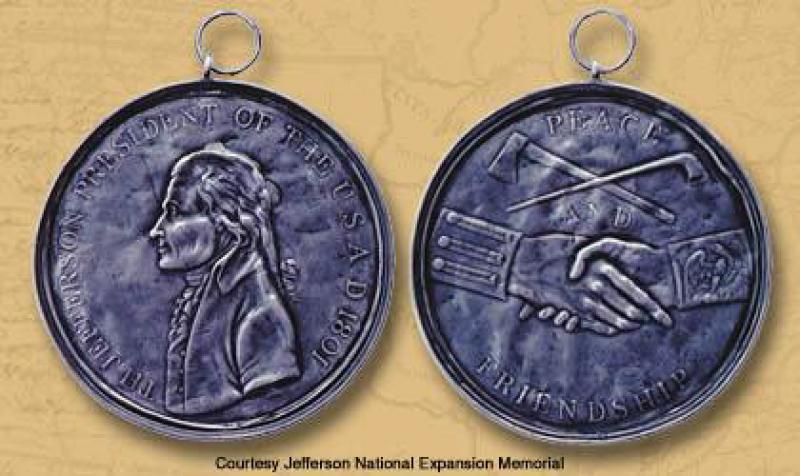

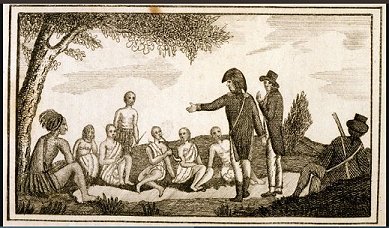

Whenever the expedition met a new Native tribe, Lewis delivered a long peace and friendship speech, painstakingly translated sentence by sentence through several languages. Today, the peace speech sounds pretty aggressive and a little cringe-worthy: “Avoid the counsel of bad birds; turn your heel from them as you would from the precipice of a high rock. …” The American flag would be on prominent display. The captains gave Native leaders (or those they mistook as Native leaders) military jackets, peace medals with Jefferson’s visage on one side, pipe tomahawks, flags, and printed certificates of good behavior with blanks for the name of the tribe, date of the encounter, and name of the “chief.” The expedition men suited up for the councils in their best military attire and paraded in military formation. At this point, Captain Lewis usually trotted out his air gun and demonstrated its magic. If the journals are accurate, the air gun demo never failed to signify to Natives that these strangers had mighty powers for which there was no obvious explanation. Plus, some awesome gear.

Lewis’ Newfoundland dog, Seaman, was also part of the medicine show. Lewis reports that the Natives were delighted and impressed by Seaman’s “segacity.” The dog could do tricks: fetch, roll over, shake hands, sit, play dead — the usual stuff. Native American dogs were not house pets. They had greater affinity with wolves than Newfoundlands or any other domesticated dog. No wonder the Natives found Seaman’s tricks uncanny.

One journal entry by Meriwether Lewis, among the Shoshone on August 17, 1805, covers a lot of this ground:

“We gave the 1st Chief an uniform coat shirt a pair of scarlet leggings a carrot of tobacco and some small articles to each of the others we gave a shirt legging handkerchief a knife some tobacco and a few small articles we also distributed a good quantity paint moccasin awls knives beads looking glasses &c among the other Indians and gave them a plentiful meal of lyed corn which was the first they had ever eaten in their lives. They were much pleased with it. Every article about us appeared to excite astonishment in their minds; the appearance of the men, their arms, the canoes, our manner of working them, the Black man York and the sagacity of my dog were equally objects of admiration. I also shot my air-gun which was so perfectly incomprehensible that they immediately denominated it the great medicine.”

This revealing passage says a great deal about imperialism. Scores of explorers — Columbus, Captain James Cook, Mungo Park, Alexander Mackenzie, Bougainville, and Lewis and Clark — employed their more advanced industrial technology to impress or intimidate Natives. Many Natives were seeing these European devices for the first time.

Indigenous cultures were especially alert to mystery, to non-explainable phenomena, to evidence that things worked not just by the laws of physics and engineering but by some mysterious energy (the Lakota wakan) that could not be fully controlled but might be coaxed or propitiated. The minute Europeans realized that they possessed a kind of technological mojo and that careful use of it could accomplish important goals that might be harder to achieve with mere diplomacy, they began to incorporate such “magic” into their encounters with Natives.

Lewis and Clark were better than most, but they were not unwilling to use their technology medicine show when necessary.

The Lewis and Clark Medicine Show

On the return journey, effectively bankrupt and in need of food, principally dogs, the captains gave what limited medical care they had with them to a few Indigenous individuals with maladies (blindness, rheumatism, respiratory troubles). When the captains’ “cures” seemed to give comfort (psychological, more probably than physical), they suddenly found their clinic waiting room crowded. Dozens of Natives came to seek medical help. Lewis and Clark did not have much to offer (and didn’t know much), but they lavished a bit of ritual on their few and all-purpose chemical ministrations. In this way, they won renown among their Native hosts.

Lewis provided some interesting commentary about this frontier enterprise on May 5, 1806. The expedition was near the confluence of the Snake and the Clearwater rivers at today’s Lewiston, Idaho:

“Capt. C. gave an Indian man some volatile liniment to rub his knee and thigh for a pain of which he complained, the fellow soon after recovered and has never ceased to extol the virtues of our medicines and the skill of my friend Capt. C. as a physician. This occurrence added to the benefit which many of them experienced from the eyewater we gave them about the same time has given them an exalted opinion of our medicine. My friend Capt. C. is their favorite physician and has already received many applications. In our present situation I think it pardonable to continue this deception for they will not give us any provision without compensation in merchandise and our stock is now reduced to a mere handful. We take care to give them no article which can possibly injure them.”

So, the remedies were a chemical wipe and an eyedrop. For this, Clark was their “favorite physician” and was given a steady supply of food and several horses, one or two of which were splendid. I respect Meriwether Lewis for expressing some uneasiness about this dubious enterprise (mostly placebo stuff), which continued for more than a month: “I think it pardonable,” i.e., under the desperate circumstances. At least Lewis takes the Hippocratic oath: “We take care to give them no article which can possibly injure them.” On May 19, the expedition camp was visited by “a train of invalids.”

On May 19, William Clark’s journal entry has an almost biblical ring. I’m sure he never thought of himself as a true healer, but if the medicines Lewis and Clark administered gave people relief and brought measurable improvement, even if only because the patients felt they had to trust beings who carry so many forms of power in their baggage, it is clear that the Natives were impressed by that power and the kind of people who could apply it for good. In a lovely, ironic way, the incident creates a dialogue between a child in Idaho and a child in Roman Palestine:

“They also,” [Clark wrote], “brought forward a very young child whom they said had been very sick — . I administered eye water to all, two of the women I gave a cathartic, one whose spirits were very low and much hiped.”

Here “much hiped” means seriously depressed. Here Clark “saves” a Native child.

There were two other employments of the expedition’s magic, neither of which is very admirable.

York’s Magic

One: Clark’s enslaved body servant, York, had no rights back in Virginia and Kentucky. He could be bought and sold, whipped, beaten, disfigured, maimed, or even killed back in “civilization,” but on the upper Missouri, York was “metamorphosed” (to use one of Mr. Lewis words) and to the Indigenous people he was fascinating, exotic, and undoubtedly “powerful.” Most American Indians had never seen a Black man before. Some refused to believe it. York’s uniqueness caused some Natives to wonder if he was a spirit being or a shaman or even if he had special status with the expedition. Some of the Native women sought his DNA. One gruff Hidatsa leader spit on his hand and tried to rub off what he reckoned was ceremonial paint.

When Lewis and Clark realized that York could be an asset, they occasionally used that Native misunderstanding to their benefit. Among the Mandan villages, Clark ordered York to dance for the Natives. York was a big man. He must have been mesmerizing. The fact that he was treated better by Natives than by his countrymen is one of the expedition’s persistent ironies, one of its reverse discoveries. Among the Mandan, York even pretended he was a wild creature (a “bear”) caught and partly tamed by William Clark. He chased mock-terrified children around the earth lodge village.

And then …

When York and Clark got back to “civilization,” Clark reverted to his former status as a severe white slaveholder. When York sought manumission or at least the right to stay back in Louisville with his family, Clark beat him severely (“gave him a trouncing,” Clark said). Clark even threatened to sell York into the Deep South.

Two: Clark was usually an even-tempered man, more relaxed and approachable than Meriwether Lewis. But he occasionally got angry, and though we need to read between the lines a bit (it’s an early 19th-century document), you can see that a month into the return journey, he had lost all patience with a community of Indigenous people who lived near the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette rivers. When Clark entered a semi-communal dwelling (uninvited) to purchase wappato root (a swamp potato much needed by half-starved American explorers), the Natives refused to sell the swamp bulb for anything Clark had to offer. In his snarky journal entry, he described these locals as “sulky,” a term he occasionally employed to describe non-cooperative Natives.

Clark did a little magic show to break the impasse and get the foodstuffs he needed:

“I entered one of the rooms of this house and offered several articles to the Natives in exchange for wappato. They were sulky and they positively refused to sell any. I had a small piece of port fire match in my pocket, off of which I cut a piece one inch in length & put it into the fire and took out my pocket compass and set myself down on a mat on one side of the fire, and a magnet which was in the top of my inkstand the port fire caught and burned vehemently, which changed the color of the fire; with the magnet I turned the needle of the compass about very briskly; which astonished and alarmed these Natives and they laid several parcels of wappato at my feet, & begged of me to take out the bad fire; to this I consented; at this moment the match being exhausted was of course extinguished and I put up the magnet &c. This measure alarmed them so much that the women and children took shelter in their beds and behind the men, all this time a very old blind man was speaking with great vehemence, apparently imploring his god. I lit my pipe and gave them smoke & gave the women the full amount of the roots which they had put at my feet. They appeared somewhat pacified and I left them and proceeded on …”

Something is disquieting about this story. Clark plays Merlin, puts a small piece of colored fuse in the fire, turns a compass needle without touching it, and scares the living daylights out of Natives minding their own business in their private homes. Natives who would be glad to trade if they had any surplus food but who were protecting what little they had in this lean time of the year. Clark terrifies them so much that “a very old blind man was speaking with great vehemence, apparently imploring his god.” Try to imagine this scene. Women begging Clark to take the dark magic away. An old man speaking in tongues. When the horrified Natives quickly rounded up a few “parcels of wappato” and placed them at the strange being’s feet, begging him to “take out the bad fire,” all we get from the Wizard Clark is, “to this I consented.” When I first read this story 40 years ago, I found it joyous; now I find it sad.

Clark reports in his journal that he paid fair market value (who set the exchange rate?) for the roots. As he hastened away with enough wappato root to give each of the expedition’s men a slice or two, Clark noticed that the Natives were “somewhat pacified.” Imagine the conversations that began the minute Clark was safely out of range. We’d give anything for a transcript.

As my friend Joshua Jay told me over dinner the other night, magic cuts both ways. There is magic as entertainment and magic as witchcraft: recreational magic or dark magic.

Clark, of course, was doing what he had to do to feed his hungry men. On most occasions, he was an extremely honorable man. Necessity is the mother of invention. The flaming fire routine is one of humanity’s oldest magic tricks. What child is not astonished when she first sees a magnet in action? I’m still astonished by magnetism, and if you ask me to explain it, my answer will be so scientifically garbled that it’s easier to say it’s magic, like gravity.

Beginning tomorrow, as I head down the Ohio River corridor into the heartland, my magic friend Josh disappears, which is one of the more disturbing results of modernity and mobility. But I hope not forever.

For Clark, I have only one question. Why did you have your inkstand on a shopping trip into a Native American longhouse?