Clay begins his 2025 Lewis and Clark transcontinental journey in the land of Thomas Jefferson, the patron saint of the famous 1804-1806 expedition.

Editor’s Note: Clay Jenkinson has begun his 2025 Lewis and Clark transcontinental journey in the land of Thomas Jefferson, the patron saint of the 1804–1806 expedition. Clay launched his trek at Jefferson’s second home at Poplar Forest on May 6. He followed that with a talk at the Lewis and Clark Exploratory Center in Charlottesville on May 10. Clay says that to understand the famous Corps of Discovery, it is essential to start with a look at the fabulous and whimsical mind of Thomas Jefferson. Here is Clay’s report.

Jefferson bought the Louisiana Territory in 1803, doubling the size of the American republic with a single stroke of his pen — three cents per acre. A year later, Jefferson sent his protégé, Meriwether Lewis, into the American interior to make an inventory of that transaction, the trans-Mississippi territory, 828,000 square miles altogether, and to make what for white people were discoveries. At the same time, Jefferson sent out other, less well-remembered explorers to fill the continental “canvas,” as he put it, with data. Jefferson had a special love of latitude and longitude. He was particularly interested in how the rivers of America interlocked. He viewed them as the commercial highways of the United States in that era before roads replaced trails. Jefferson’s instructions to Meriwether Lewis, dated June 20, 1803, represent one of the great documents of the Enlightenment.

Nobody in the United States thought more or knew more about the West than Jefferson. When he was in Paris (1784–1789), he liked to stroll among the bookshops on afternoon walks and “put aside” for later delivery (he was an aristocrat) any books about the interior of America. He read those books avidly. Jefferson became a one-man clearinghouse for information about the American West. On that basis, he envisioned what he called “an empire for liberty,” such as the world had never previously seen.

And yet …

Thomas Jefferson lived in the last age of fundamental ignorance about how the world worked. He lived on the cusp of the 19th century, during which scientists would make gigantic strides in understanding everything from the formation of clouds to the nature of plagues. Jefferson was just a generation behind in discovering and consolidating our modern understanding of the universe and everything in it. Just think of what the Sage of Monticello did not know.

Thomas Jefferson did not know the dinosaur. The mammoth, the mastodon, and the Megalonyx (which he described in a learned paper for the American Philosophical Society) were his fantasy quadrupeds, his “dinosaurs.” Actual dinosaur fossils were first recognized during his retirement years. Imagine what Jefferson would have thought of the T. rex or the Triceratops! For most of his life, Jefferson did not believe in extinction. He had no idea of long geological time, once suggesting that the universe might be as old as 60,000 years. He was unaware of the age of the universe or the age of the Earth. Jefferson thought the Natural Bridge in Virginia, which he purchased in 1774, was worth a trip across the Atlantic to see and paint. What if he had seen Arches National Park, Canyonlands, Mount Whitney, the Tetons, or the Grand Canyon? If peeping down from the top of the Natural Bridge gave him “a violent headache,” what would peering into Canyon de Chelly have done to his 18th-century mind? “It is impossible,” he wrote of the Natural Bridge, “for the emotions arising from the sublime to be felt beyond what they are here.” Really? Then how do you react when you peer over the abyss of the South Rim of the Grand Canyon?

I have just read in an excellent book about the Colorado River (River Notes by Wade Davis) about something called the Ordovician or Silurian extinctions, “a period of 130 million years that saw … the mass extinction of some 60 percent of marine life.” That would blow Jefferson’s mind. That the Earth proliferates life forms that it later casts off unceremoniously; that the life force is tenacious and yet the Earth erases almost all species in what, in geologic terms, is a mere speck of time. Nothing, no species, is sacred. There have already been five mass extinctions in which almost every living thing on the planet was wiped out; humans have no rational basis for believing that we will escape the sixth extinction. Talk about a “violent headache.” How would Jefferson have assimilated these basic truths? How would he have responded to peeping over that abyss?

The notion that God created the world in just six days, the horned toad as well as the gazelle, mosquito, tick, horsefly, as well as the pronghorn antelope, did not make any sense to Jefferson, but his primary quibble was with “six days.” The rest — that God deliberately created the muskrat and the buffalo precisely as Jefferson observed them in his lifetime — seemed reasonable to him. He did not believe that species evolve from less to more complexity and that humans are just the apex of an evolutionary dynamic that has graduated us beyond the ingenuity of all other primates. Jefferson lived in the last era when you could believe, at least to a certain extent, that God had deliberately created everything in a single moment of deliberate design and placed each species in its proper link on an elaborate chain of being and that nothing could ever be extinguished without damaging the integrity of the entire chain of being. At the end of his life, he was beginning to accept the idea that some species, at least, might have gone extinct.

Jefferson believed that geology is, on the whole, the study of mere scratches in the Earth. He was impatient with metaphysics, which, in this case, meant the intense European debate between Vulcanism and Neptunism, about whether the Earth changes form drip by gradual drip or in appalling convulsions from time to time. This, like every other abstract argument, bored him. To the extent that he was interested in geology, it was in applied geology — salt licks and the fall line of rivers — that got his attention.

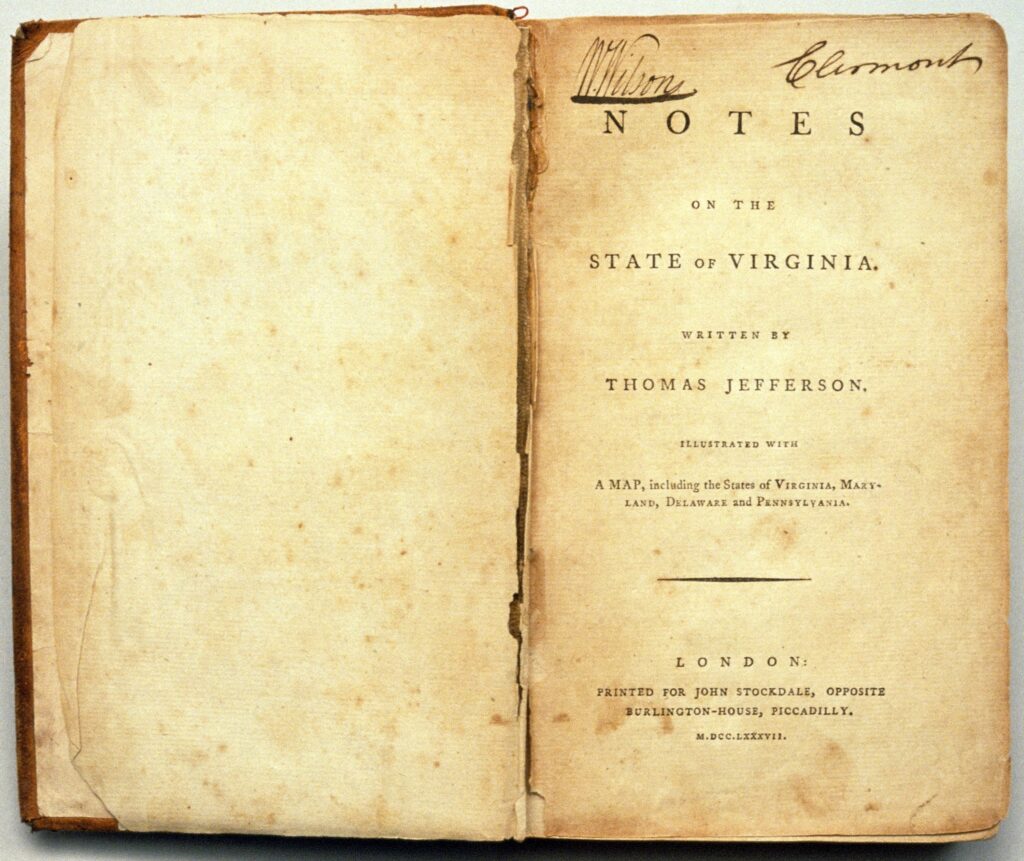

Jefferson wrote only one book. In Notes on the State of Virginia, written between 1781 and 1784, Jefferson described the Peaks of Otter near the Natural Bridge in western Virginia. He said that the peaks at about 4,000 feet were possibly the highest mountains in North America.

Say what?

Here’s what he wrote: “The mountains of the Blue Ridge, and of these the Peaks of Otter, are thought to be of a greater height … than any others in our country, and perhaps in North America.” This had implications for Lewis and Clark. If the captains traveled through Montana carrying that intellectual baggage, imagine their surprise when the relatively low range they crossed to get into the Columbia River basin (the Bitterroots) was twice as high as the Peaks of Otter, and some mountains in America would prove to be nearly four times that high? If Meriwether Lewis expected to lug the expedition’s 20 tons of gear through a western “Cumberland Gap” (1,631 feet), he was sorely mistaken, in both senses of the word.

Jefferson was as sophisticated a reader and thinker as anyone in the Western Hemisphere in the year 1805. He was one of the best generalist polymaths in the world. He prided himself on knowing about an extensive range of subjects but never lorded it over anyone. He always treated others with humble respect, as if he were nothing more than a young, curious man, eager to share what he was learning with others, and not in any way suggesting his intellectual superiority.

Jefferson lived through the last gasp of barbaric medicine. In Jefferson’s time, we barely understood the circulation of the blood. We hadn’t yet figured out how viruses travel or determined the cause of such pandemics as smallpox or yellow fever. During his lifetime, we were just about to figure this out. When Jefferson learned of Dr. Edward Jenner’s discovery of the true smallpox vaccine in England, he wrote him a letter in 1806, one of the greatest any president has ever written. Among other things, Jefferson wrote, “You have erased from the calendar of human afflictions one of its greatest. Yours is the comfortable reflection that mankind can never forget that you have lived.” Who would not have wanted to receive that letter?

Four of Jefferson’s six children died in their childhood of diseases easily addressed in our time. Physicians were bleeding and purging back then, with Dr. Rush’s patented emetic pills, which the Lewis and Clark expedition men called Dr. Rush’s Thunderclappers because they eliminated the contents of the digestive system more or less immediately. And that was better than bleeding. We all know that President Washington was bled to death in the last 72 hours of his life. The physicians who were attending him didn’t know what to do about his strep throat, so they bled Washington until he died, as much from dehydration as anything else. Jefferson witnessed bloodletting once at Monticello and said never again.

If Moses had visited Jefferson’s plantations, he would’ve understood that agricultural practices were essentially unchanged for millennia. In the best kitchens of the era, cooking was done by way of open fires. That’s why the kitchens were built away from the house, so that the house would be spared when they burned down, as they routinely did.

It was still a three-mile-per-hour world. Most of the commercial traffic in America moved on water — rivers, bays, and lakes. The best toilets were no better than the notorious “Groover” of western whitewater raft trips or a chemical toilet you might put in an isolated cabin. Benjamin Franklin had made startlingly important discoveries about electricity and had written the first learned papers about this subject for the Royal Society in London. That’s what made him famous. The world thought of him as a savant. We erroneously think of him as a witmonger with a kite.

Central heating was still decades away. They were still lighting their lamps with whale oil and tallow. It was 75 years after Jefferson’s death that the internal combustion engine was developed. He lived long enough to see the potential for steam locomotion. In fact, his granddaughters had an excursion ride on a steamboat in the James River after his retirement. I believe it was in 1815. Jefferson spent years trying to perfect cisterns that would not leak at Monticello. Today? A quick stop at Home Depot, and the problem is solved. He dabbled with a crude early version of the thermal “cooler” to send butter from one place to another without it melting. He loved skylights, but he could not make them entirely leakproof. (Get in line, Mr. Jefferson!)

Most people in that era never traveled more than a few dozen miles from their birthplace. When individuals of the time, including Jefferson, wrote letters to each other, the first question they asked was some version of “Is everyone still alive? Tell me of the people who have passed. Who has been born, who is sickly, who died prematurely, who died in childbirth, who died of the pox or the yellow fever?” When people traveled more than a few hundred miles from their home community, their kin and friends reckoned that they would never see them again.

That was how close death was to people like Thomas Jefferson. “I am born to lose everything I love,” Jefferson wrote to his European girlfriend Maria Cosway, after surviving the death of his parents, his 33-year-old wife, his closest friend Dabney Carr (at 29), and four of his six children.

It’s hard for us to see the world as the 18th-century people saw it, because we are so accustomed to our own paradigm. We assume that life delivers central heating, running water, electrical lighting, water heaters, air conditioning, and flush toilets. In our world, these amenities are regarded as automatic, universally expected, and available even in the least desirable houses and apartments (at least in the fully developed world).

When Jefferson traveled between Monticello and Washington, D.C., several times per year, either on horse or with a carriage of some sort, on terrible roads, which were little more than paths, he had to ford eight rivers. Think of that. Think of Donald Trump or Bill Clinton fording a running river on a horse. And yet for Jefferson, this was a relatively routine thing. Such was travel. He did not make a big deal out of it. He knew horses. He was an expert, a master of the transportation systems of his time.

It blew President Jefferson’s mind when Alexander von Humboldt told him he had found mammoth bones above 10,000 feet in the Andes of South America. Why? Because Jefferson had no concept of plate tectonics or the thrusting up of landmasses from below. You can feel his brain trying to process that data using the cosmological paradigm that was then available. He finally acknowledged that “ignorance is the softest pillow on which we can lay our heads.”

Jefferson thought that because we have consciousness in the upper sectors of our brains and think of ourselves as rational beings, that’s who we are. He was entirely unaware of the much more complicated thing we actually are, thank you, Freud and Jung. Jefferson thought that because we have that reasonable surface consciousness, we can all learn to be our best selves through habit and good education. He let himself believe that humans in America, with our geographic and natural resource advantages, on this new tabula rasa of a continent, with the help of highly educated and enlightened leaders like John Adams and James Madison, could do something like perfect life on Earth if we kept at it. We now see that Jefferson was a utopian. The concept of the “perfectibility of man” can only exist in the pre-Freudian imagination. After Freud, the perfectibility of man had to compete with the tenacious reptilian core that roils beneath the Enlightenment surface.

One final point about Jefferson’s delightful ignorance of the way the world works. He had the notion that somewhere in the American West there was a mountain of pure salt. He told Congress, “This mountain is said to be 180 miles long and 45 in width, composed of solid rock salt, without any trees or even any shrubs on it.” He urged his explorers, Andre Michaux (1793) and later Lewis, to keep their eyes open for the possibility that live mammoths still grazed the savannas of the American interior. He was so open to the idea of mammoths and mastodons that his Federalist detractors employed the adjective “mammoth” to ridicule Jefferson’s credulity in every possible instance, from “mammoth cheese” to “mammoth bread,” just as we attach the word “gate” to any scandal of our time, after the Watergate scandal of 1972–75.

Jefferson hoped the great rivers of the West would interlock in a human-friendly way so that commercial boat traffic could make the portage in half a day or so between the Missouri and the Columbia rivers, with the Platte, the Red, and the Colorado near at hand. He believed the mountains of the West would not be higher than the Appalachians, but also that they would be configured in perfect symmetry with the eastern coastal ranges. He reckoned that the entire American West was as well-watered as the Ohio Valley. What would he have thought of Utah? He wanted to carve perfectly square states west of the Appalachians so no state would have more territory than another. He believed that American Indians would choose willingly to be assimilated into the dominant culture for an improved and more secure way of life. He believed slavery would magically dissipate from the American scene, like fog when the sun rises.

Thomas Jefferson believed in the perfectibility of Man and that if we worked hard at it, we could create the world’s first sustainable agrarian republic. Though we have sobered up in the last decades to the point of persistent national disillusionment, we are all deeply fortunate to have had a whimsical dreamer at the start of our national experiment.

But if you were Meriwether Lewis returning from 28 grueling months on violent rivers and snow-capped mountains, you might wish to quibble a little with the Sage of the mountain … over a glass of fine Bordeaux wine.