A short dissertation on my long infatuation with dictionaries.

Bismarck, North Dakota — A word about dictionaries. I love them! Actually, it’s out of control. I own approximately 30 dictionaries, most of them abridged, but I also have five or six of the finest dictionaries in the English language: the Random House Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language; Webster’s Third New International Dictionary and, perhaps even better, Webster’s Second New International Dictionary. The Second belongs to a more prescriptive school of lexicography — there are rules; obey them, please.

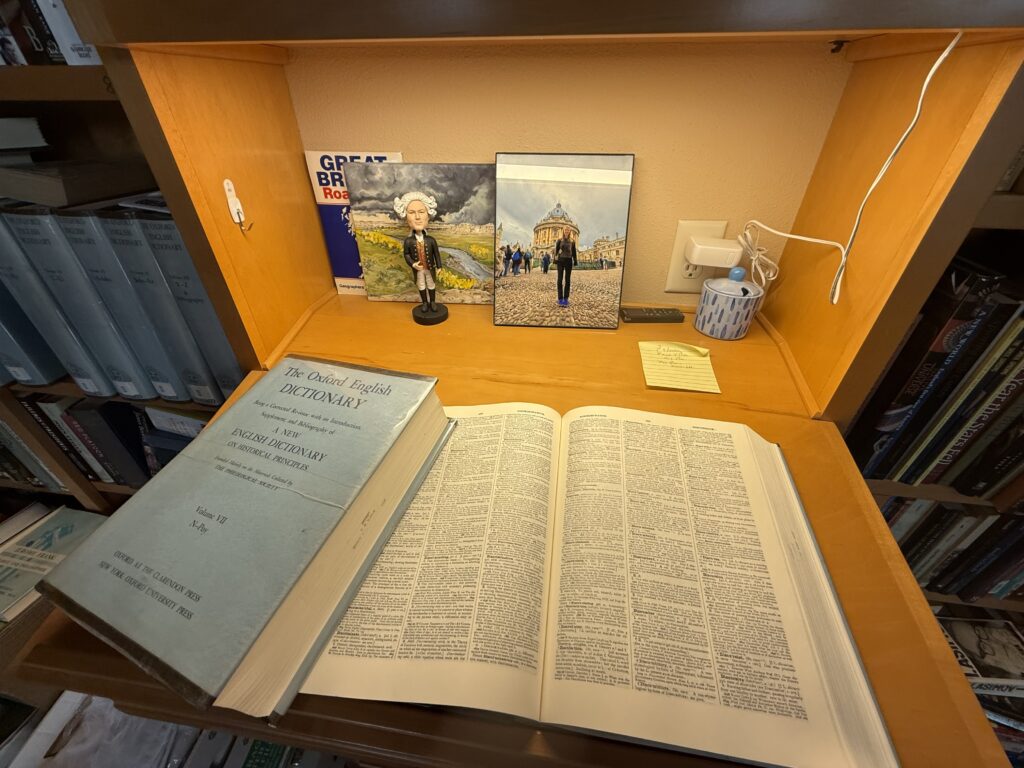

I also have all 13 glorious folio volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), possibly the greatest dictionary in the world. I have two versions of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. And downstairs in my lower library, I have that one-volume blue boxed OED, with four miniature pages printed on a page, in a font so small that it now feels like one of those grains of rice on which the 23rd Psalm is written. It was a Book-of-the-Month premium — way back. I never consult it now. It would require a microscope, but it makes me happy. It reminds me of the time when I realized that language was more than the words that come out of our lives on a daily basis.

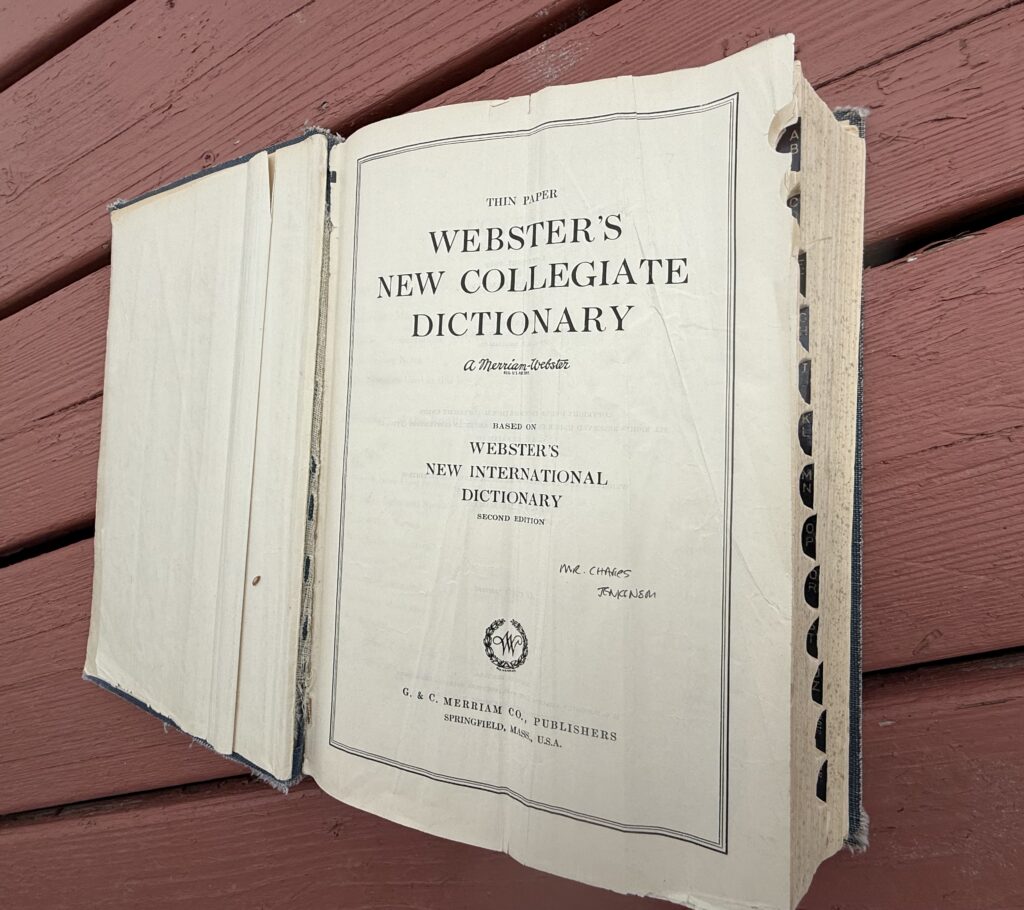

Finally, I have 10 or 15 versions of Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary.

I used to give the latest New Collegiate as a high school graduation gift, but if I tried such a stunt today, students would either scorn me or not know quite what they were holding in their hands.

At any rate, I’m writing a foreword to a new (and excellent) book on the geology of the Lewis and Clark expedition by John Jengo. I’m trying to explain that geology was in its infancy when they went west (1804-06). There was far more mystery in the rocks then than knowledge. Even Jefferson, a sophisticated man of the Enlightenment, regarded himself as both up to date and pretty daring when he wrote that the universe might even be as many, wait for it, 60,000 years old! Even so, Lewis and Clark did a splendid job describing what they encountered in at least five bioregions using basic English and a handful of current mineralogical terms. They didn’t have our geological vocabulary or sense of how all the sedimentary layers were laid down and where volcanism came in because those taxonomies were yet to be invented! However, their general, mostly plain English descriptions are so careful and comprehensive that today’s geologists can understand exactly what Lewis and Clark were looking at. Jefferson wrote that Lewis was given to “exact observation” and “a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves.” No wonder Jefferson chose Lewis to lead the expedition.

The limits of earth sciences in Jefferson’s time are exemplified in the following example: On September 10, 1804, in today’s South Dakota, the expedition found partial fossils of what we now think was a plesiosaur. They described it with their usual care, but they could not really fathom what it was. They called it a big fish. Why? Because the idea of the dinosaur had not yet gelled in the Euro-American consciousness. Not only was there no word “plesiosaur” in 1804, but no word “dinosaur” at the time! It wasn’t until around 1809, after Jefferson left the presidency, that Georges Cuvier in France began to recognize, describe, and characterize the dinosaur (literally, the terrible lizard).

To get on with the foreword I was writing, I wanted to know exactly when “dinosaur” first appeared in English. Where should you turn? There is only one reliable place, Volume III of the OED (D-E). I got up from my chair, walked to the living room standing desk, pulled out the hefty volume, and looked it up. The word dates to 1841. It was proposed by an anatomist named Richard Owen in Britain in a learned paper he apparently read before the British Association for the Advancement of Science that year. Lewis was dead. Clark was dead. Thomas Jefferson was 15 years dead.

A principal axiom of the humanities is that you can only see what you are prepared to see. The lens you wear determines what you see. You only know what you develop a vocabulary to process. I have read Lewis and Clark without a geological or mineralogical lens all my adult life. I never even thought of such a thing. Not that I’m bored with geology (well, sometimes!), but because I had been informed in the books of virtually all Lewis and Clark expedition experts that while they were outstanding observers of flora and fauna, they did not have much to say about rocks. This fallacy has an interesting reason, but that story is for another time. But now that I have been reading the journals after reading the manuscript of John Jengo’s book, I see geology in almost every sustained journal entry, especially — this is a surprise — in Clark’s entries.

I will miss my dictionaries while traveling the Lewis and Clark Trail this summer. I am taking my favorite Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary (the second) and have online access to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The online version is searchable! As Joe Biden said of Obamacare, “That’s a big f…..g deal.”

What is the best word to describe this road trip I am about to undertake from a linguistic point of view? A sojourn? A journey? A trek? An expedition? An adventure? An exploration? A recreation? A pilgrimage?

I prefer the poetry of sojourn, but the correct term here is journey, which starts this week!

See you down the road.