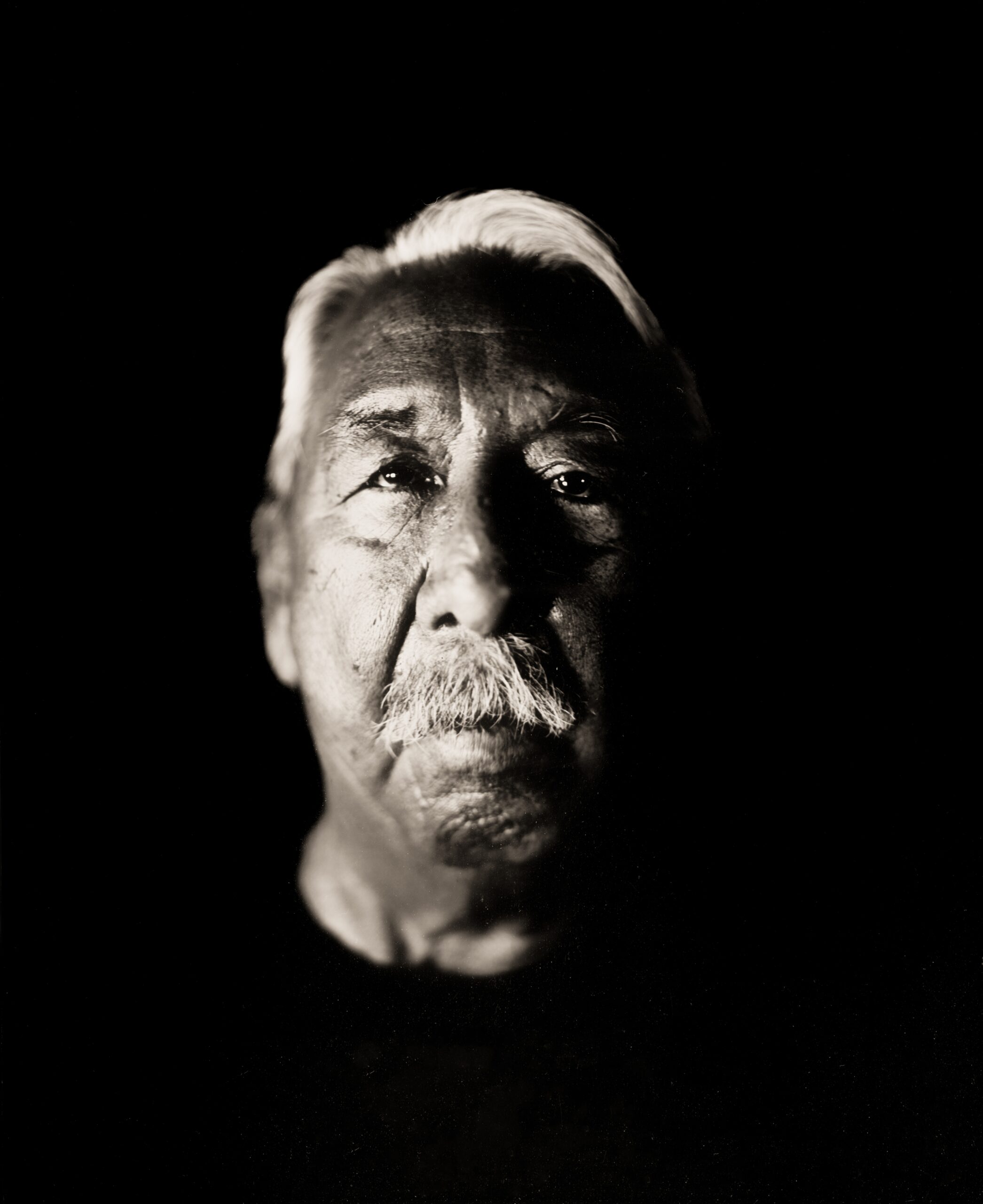

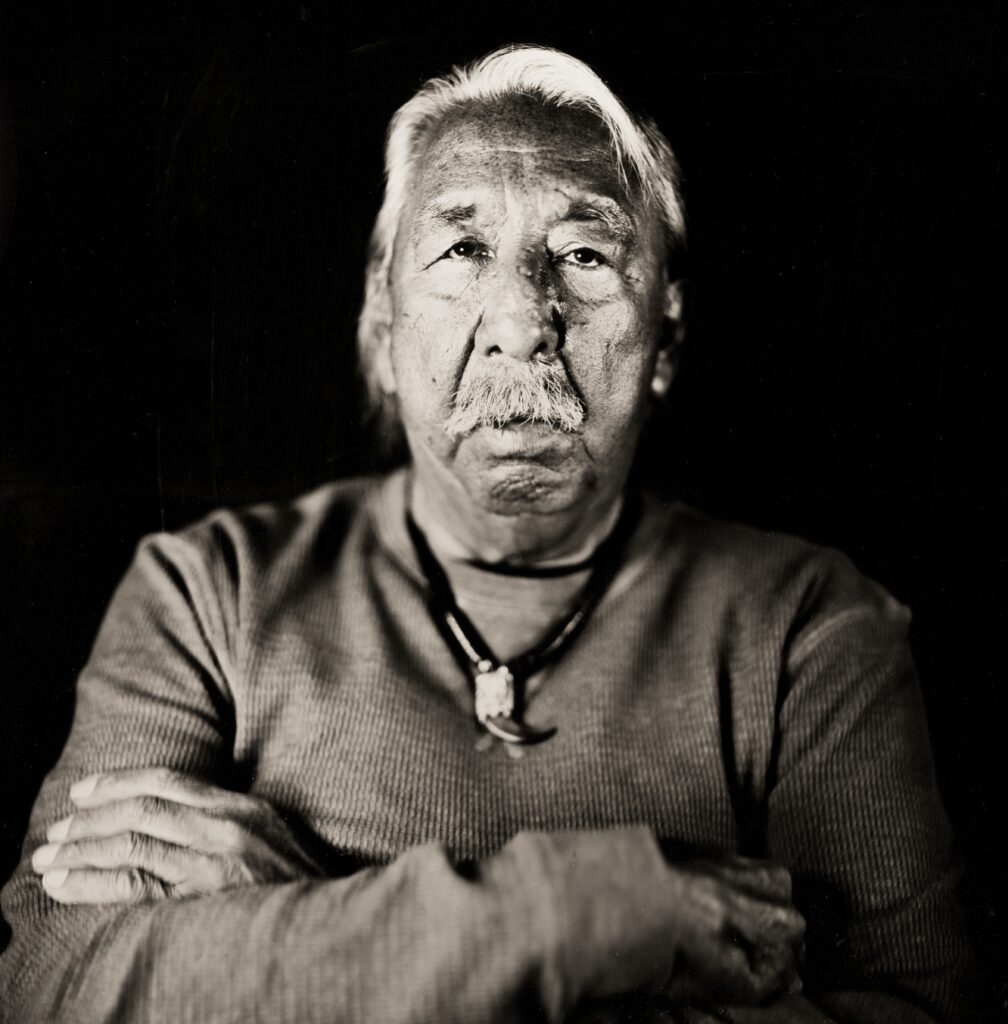

Earlier this year, President Biden commuted the prison sentence of Leonard Peltier. This week, noted “wet plate” photographer Shane Balkowitsch visited Peltier at Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota, where he made a series of historical portraits of the 80-year-old Native American activist. Balkowitsch’s portraits of Peltier are published here for the first time.

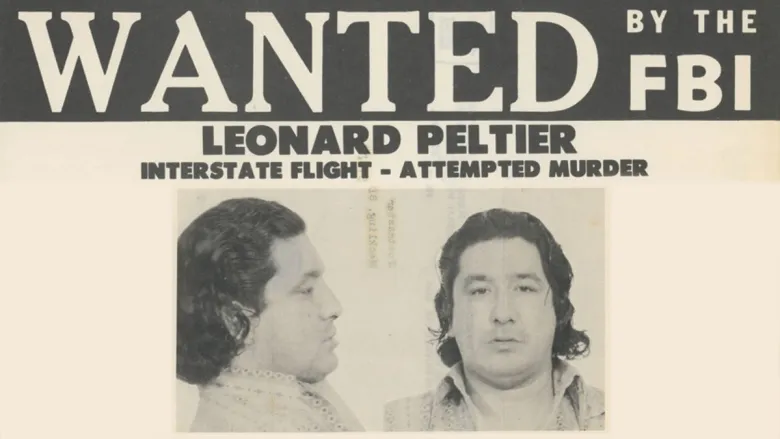

Editors Note: Today, Listening to America has the distinction of publishing a number just-released photographic portraits of Native American activist Leonard Peltier. In one of his final acts as president, Joe Biden commuted the sentence of Peltier, who in 1977 was convicted of murdering two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Peltier, now 80, has been in federal prison for the last 49 years.

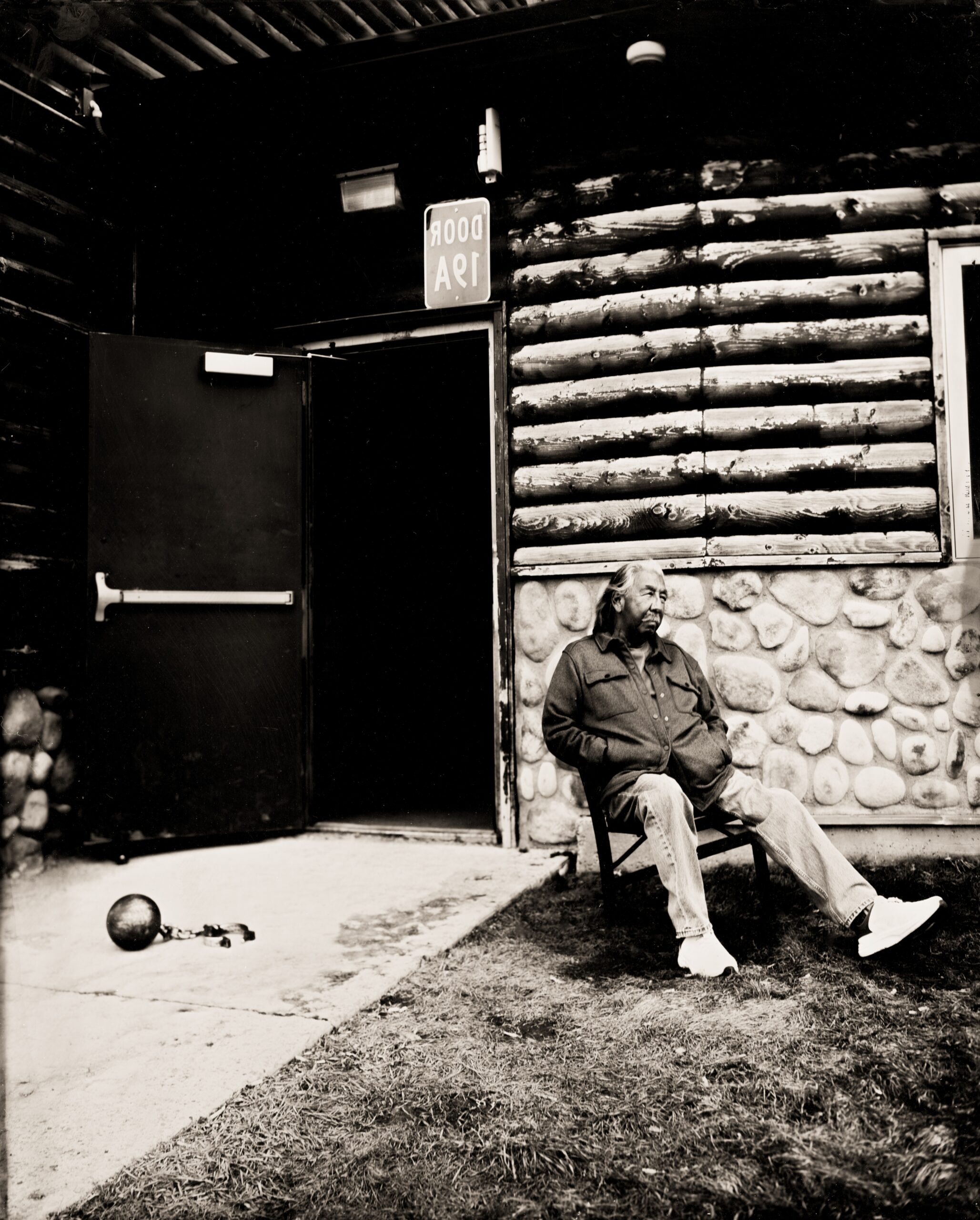

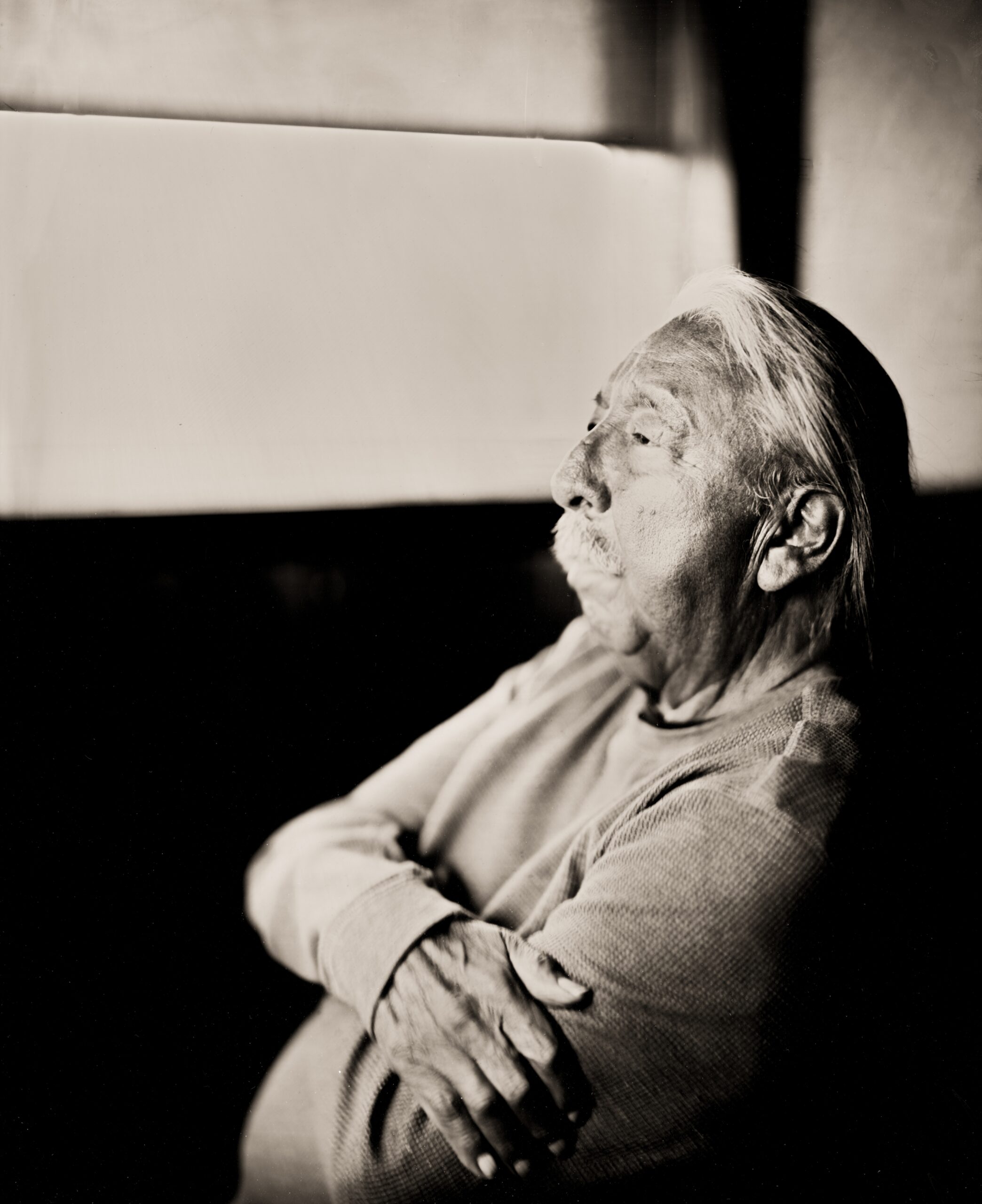

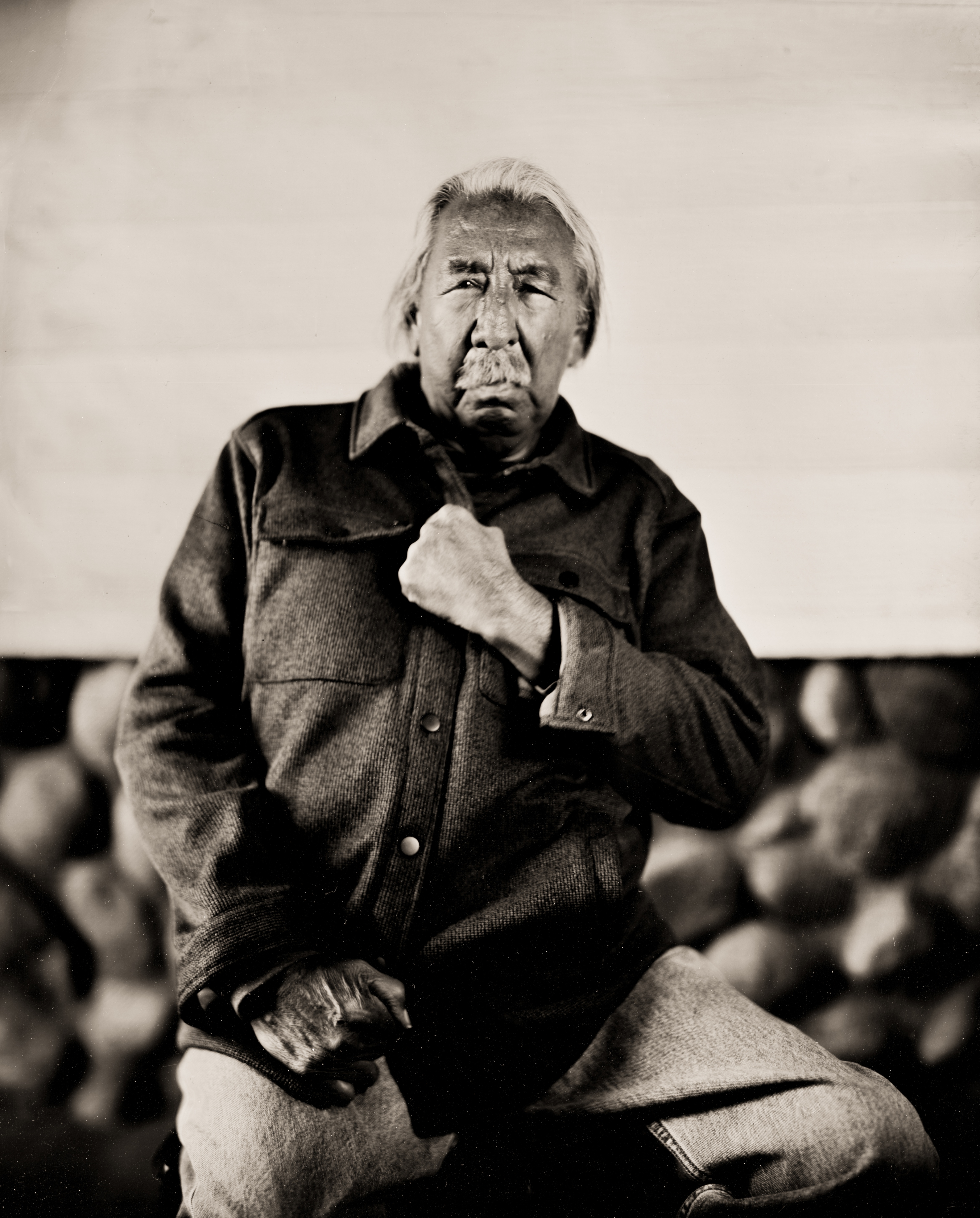

Clay’s friend Shane Balkowitsch of Bismarck, ND, was invited to the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation last week to photograph Peltier, who is under house arrest near Belcourt, North Dakota. Balkowitsch was encouraged to take the photographs by former Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, who sat for a Balkowitsch portrait in 2019.

Balkowitsch is a collodion wet plate photographer. Retired from a career as an online entrepreneur, Balkowitsch mastered the complicated wet plate photographic process, the standard in photographic technology between 1853 and 1880, and began to take portraits of Native Americans in his studio in Bismarck, North Dakota.

So far, Balkowitsch has taken 5,335 plates of 862 Indigenous men and women from all over the United States. He has published three books of his portraits. For the second of these volumes, Clay wrote the foreword.

Leonard Peltier remains a controversial figure. His release from prison was contested by veterans of the second Wounded Knee crisis (1973-75), the families of the agents who were killed on June 26, 1975, and other groups and individuals.

Our goal at Listening to America is to listen to the widest possible range of American voices and perspectives. One of the central questions as the United States approaches its 250th birthday is how to rethink and resolve the long, tragic history of U.S. relations with Native Americans. Peltier was an important figure in the American Indian Movement (AIM) of the late 1960s and the 1970s. His book, Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sun Dance (2000), tells his side of the Wounded Knee II story. The late Peter Matthiessen wrote an exhaustive account of Native resistance at Wounded Knee, including the 1975 shootings and Peltier’s arrest and trial, in In the Spirit of Crazy Horse in 1983.

Balkowitsch made seven wet plate photographs of Peltier on March 26, 2025. These are to be deposited at the State Historical Society of North Dakota, South Dakota State Historical Society and the Library of Congress. They will undoubtedly be widely distributed and published. The New Yorker has requested to publish several of the images in an upcoming issue.

As we put this week’s newsletter to bed, Shane wrote Clay: “You got the scoop! As promised. We need to work on getting you that interview [with Mr. Peltier].”

One of Joe Biden’s last acts as President of the United States was one of his finest. On Monday, January 20, just hours before retiring permanently to private life, President Biden commuted the life sentence of Native American activist Leonard Peltier, convicted in April 1977 of killing two FBI agents at Wounded Knee in South Dakota.

Gallery of Shane Balkowitsch’s Images of Leonard Peltier:

Peltier has spent the last 49 years in federal prison.

The commutation does not clear Peltier of his conviction. But it permits him to finish out his life sentence at home. He is 80 years old. It’s about time! He has returned to the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in northern North Dakota. He is under house arrest.

Even if Peltier was guilty of the crimes for which he was convicted — which is far from clear — surely he has served long enough. His health has been impaired for many years. Older inmates in America are routinely released (often to home arrest) when their health fails. President Trump’s corrupt former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, was released to home confinement in May 2020 because of concerns that he might become infected with the coronavirus. He had served 23 months of a 7 ½ year prison term. He was 71 years old. No such relief was offered to Peltier or tens of thousands of other inmates throughout the United States.

Wounded Knee has special potency as a symbol of Native American resistance to the white conquest of North America. It was there, on December 29, 1890, that more than 200 Lakota men, women, and children, almost every one of them unarmed, were massacred by the United States Army in what is regarded as “the end of the Indian wars.” In 1973, Native American activists, led by members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), took over Wounded Knee for 71 days. Before the siege finally ended, two Native Americans had been killed, and a small number of Natives and white law enforcement agents had been wounded. Peltier was not a principal figure in the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee; he arrived from Wisconsin late in the siege to give his support to the resistance, mostly composed of Lakota activists. The shooting incident that led to Peltier’s conviction and imprisonment occurred on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation two years later, in 1975.

1975 is a very long time ago. Since Peltier’s conviction, we have had four Democratic presidents: Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden. I never expected a Republican president to pardon Peltier or commute his sentence, but as each Democrat has left office, I have hoped and even prayed that Peltier would be pardoned. Until now, no retiring president has had the courage to do so. I’ve spent time with FBI agents who were at the siege of Wounded Knee. Their view has been predictable if, in my opinion, wrongheaded. They regard the killing of fellow law enforcement agents as especially heinous, and they have waged a series of fierce behind-the-scenes campaigns to warn off any president who might have had the impulse to pardon Peltier.

Years ago, I met an FBI agent who quietly stated that Peltier was almost certainly not guilty of the crimes for which he was convicted, but, he said, Peltier “is a very bad dude” and we are better off with him in federal prison. There’s your American judicial system. The investigations of Peter Matthiessen for his 1983 book, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse: The Story of Leonard Peltier and the FBI’s War on the American Indian Movement, made it clear that the FBI and the Justice Department fudged evidence, withheld evidence, and ignored evidence to convict Peltier. In other words, even if he killed two federal officers (which he continues to deny), he was not given a fair trial.

President Bill Clinton pardoned his corrupt crony, Mark Rich, at the last hour in 2001. Rich was indicted in 1983 for $48 million in tax evasion, not to mention running illegal oil deals with Iran during the 1979-1980 hostage crisis. Rich fled the United States during the prosecution and wound up in Switzerland. In 2016-2017, President Obama pardoned several individuals who gave away American strategic secrets, but not Peltier.

Peltier’s ordeal points to some fundamental problems with the American justice system. While the rich and privileged are rarely brought to justice for the crimes they have undoubtedly committed, or — at worst — are subjected to “Club Fed” for a few months, followed by a lucrative post-incarceration career, people of modest means, and especially men (males) of color — African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic Americans — rot in our prison system, largely forgotten, with very little acknowledgment that race and class are more determinative than crime per se.

Yet here is a true Indigenous freedom fighter, defending his fellow Native Americans in the face of a phalanx of institutional oppressions and injustices, railroaded into a lifetime in prison by the U.S. court system and lawyers who knew they were violating important provisions of the Bill of Rights, refusing to permit Peltier’s lawyers to introduce exculpatory evidence that led to the acquittal of two other Natives accused of the same or similar crimes.

The two FBI agents killed on June 26, 1975, were Jack Coler and Ronald Williams. Peltier was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to two consecutive life terms. Peltier later admitted that he had fired bullets at the car in which Coler and Williams were driving through the reservation to arrest someone else.

At the time of Peltier’s commutation, the White House released a statement: “The President is commuting the life sentence imposed on Leonard Peltier so that he serves the remainder of his sentence in home confinement. He is now 80 years old, suffers from severe health ailments, and has spent the majority of his life (nearly half a century) in prison.”

Peltier’s champions have included some prominent figures in American politics and culture: Willie Nelson, Steve Allen, Sherman Alexie, Kurt Vonnegut, jr., Coretta Scott King, Noam Chomsky, Peter Coyote, Pete Seeger, Nelson Mandela, Jackson Browne, and Kris Kristofferson, among many others.

I am not suggesting that Peltier is an entirely innocent man. When he came, almost too late, to the siege at Wounded Knee in 1973, he was fleeing from an arrest warrant for attempted murder in Milwaukee. There are other allegations. The late 1960s and the 1970s were a heady and violent time in “Indian Country,” and in confronting the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the United States government, corrupt tribal chairmen, and the racism of the white people who live anywhere near Indian reservations, Native activists sometimes committed acts of trespass, lawlessness, and violence. They believed anything short of heroic resistance would perpetuate several “centuries of dishonor” and injustice.

Peltier belongs to a distinguished American tradition of resisting (sometimes with violence) racism and systemic oppression of our most vulnerable communities: Nat Turner, Gabriel Prosser, Sojourner Truth, Red Cloud, John Brown, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Russell Means, Dennis Banks, Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King, jr., and countless others.

We need not celebrate Leonard Peltier. His detractors are enraged about his release from federal prison. History will sort all of that out. But after 49 years, it was surely time to let him go home to finish his life in his Native homeland.