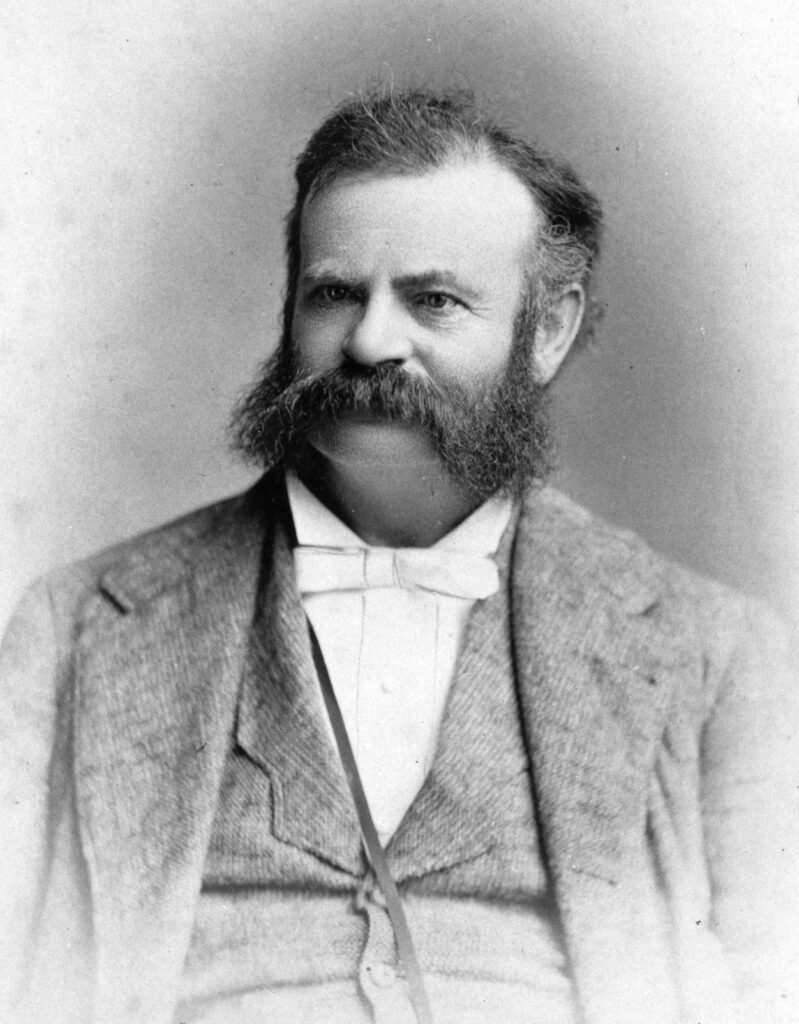

John Wesley Powell, the extraordinary one-armed Civil War veteran, was the first to explore the canyons of the Colorado Plateau by river. His remarkable story still fascinates and inspires me.

Bismarck, N.D. — a week of luxury. I’ve had almost all of every day to read. This rarely happens in my life now. I try to read for four or five hours daily, no matter where I am, but this is sometimes impossible. So when I get uninterrupted reading time, I take full advantage.

I’m reading four or five books about John Wesley Powell simultaneously. Powell (1834-1902) was the one-armed Civil War veteran who explored the canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869. He ran the Colorado from Green River Station in Wyoming all the way to Grand Wash Cliffs on the other side of the Grand Canyon. Powell found nine volunteers foolish enough to join him on that great madcap adventure.

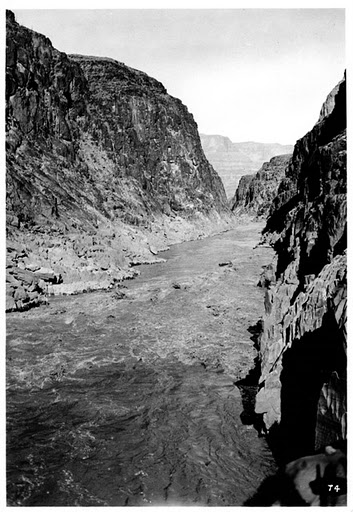

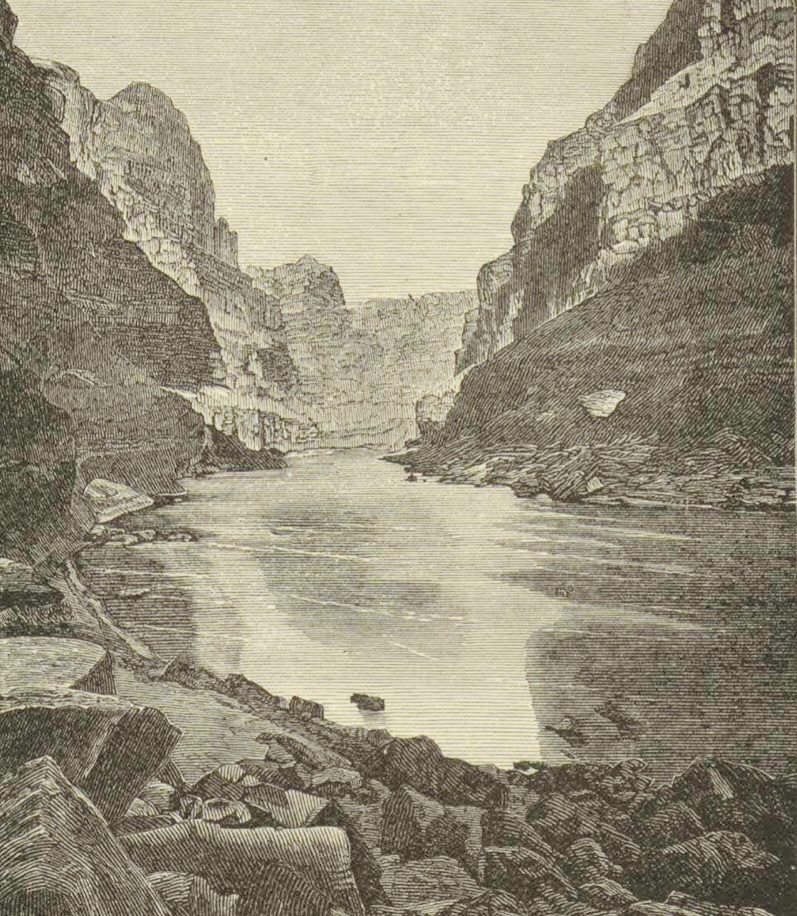

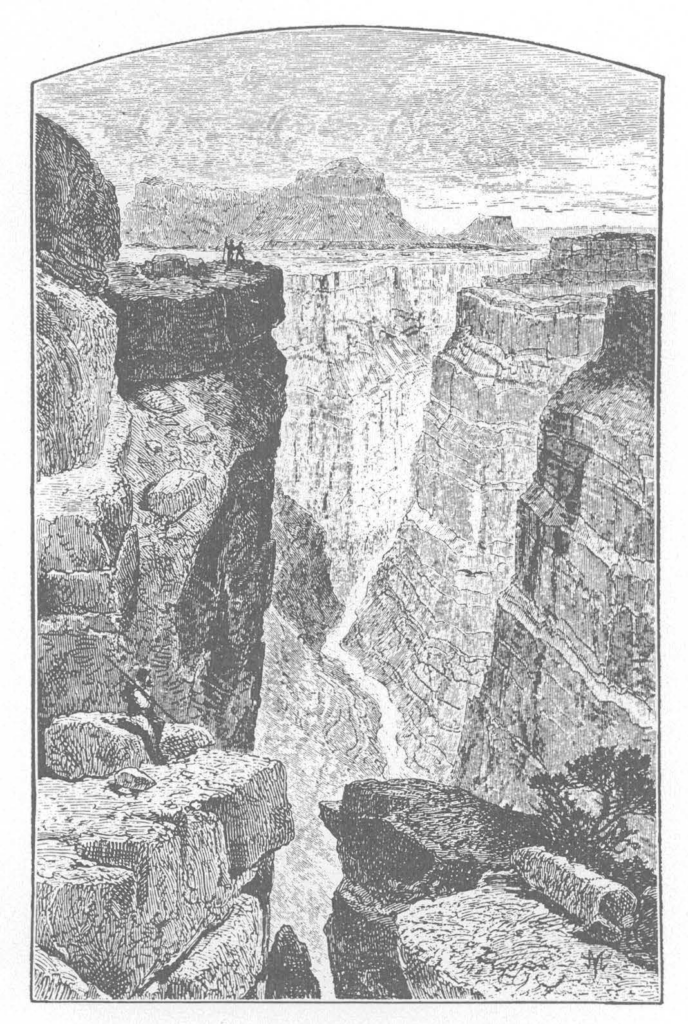

Powell published an account of the 1869 journey in 1875: The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons. Although the purposes of the float trip were primarily scientific, the canyons punished his crew so violently that the scientific endeavors were curtailed, even abandoned, and it soon became a race for survival or, as Powell put it, “a race for a dinner.” Powell’s book reads like an adventure story. Amazingly, they survived. They were in wooden boats designed for harbor duty. They rowed backwards! They had no idea what was around the next bend. They ran out of food (more or less) before they entered the Grand Canyon. There were times when they could not make a portage or lower the boats through deep rapids on long lines of rope. Even Powell, who was uninterruptedly enchanted by the sheer magnificence of canyon country, and whose prose sometimes bears the taint of over-the-top Victorian effusion, called the Grand Canyon “our prison.” By the time they were cast out of the Grand Canyon into slack water near the mouth of the Virgin River at the end of August 1869, they were emaciated, nearly naked, battered and bruised, psychologically disturbed, and wholly exhausted in both body and mind.

Not everyone who began the journey finished. One man quit at the first decent opportunity. Three others were so appalled by what became known as Separation Rapid that they abandoned the river and climbed the North Rim to walk overland to the nearest Mormon settlement, which they reckoned would be 75 miles away. They were killed — probably by Shivwits Natives, possibly by paranoid Mormons. Nobody knows for sure. The irony of their desertion is that the expedition was by then just a few miles from the terminus of the Grand Canyon. The paradox of exploration — a voyage of discovery — is that they had no way to know that.

Based on this journey, Powell became a national hero. He leveraged that fame into Congressional support for more truly scientific surveys of the Colorado River plateau. Powell became the most important advocate of government-funded science in his lifetime. He helped found the Cosmos Club and the National Geographic Society.

In my reading, at the moment, the Powell expedition is deep in the Grand Canyon, and morale is beginning to fissure. At the mouth of the Little Colorado River, expedition member George Bradley writes, “The men are uneasy and discontented and anxious to move on. If Major [Powell] does not do something soon I fear the consequences, but he is contented and seems to think that biscuit made of sour and musty flour and a few dried apples is ample to sustain a laboring man.”

The expedition’s men are laboring heroically to get over the next rapids. They know that as soon as they accomplish that — with infinite exertion — they will face another impassible rapid — and then another — and then … .

Powell was the first to float the canyons, including the Grand. The recreational float industry didn’t start until after World War II. These days, about 30,000 people float the Grand Canyon every year, mostly in rafts, a few in wooden dories (much more suitable than Powell’s boats), and even fewer in kayaks. You cannot float the Grand Canyon without danger. Accidents happen. People drown, break their legs, get heatstroke, and experience panic attacks. But if you make the journey, you can count on a statically high level of safety. It is unlikely that you are going to die and almost equally unlikely that you are going to have to be helicoptered out of the canyon. There is not much labor for paying guests. The crew does all the work, made up of young idealists who have not yet settled into life (“As long as possible,” Thoreau said, “live free and uncommitted.”) and permanent river rats, who find the Colorado River so addictive that they never leave until their bodies break down. Mostly, you sit in an unsinkable, self-bailing raft and hang on tight while expert river men and women steer you down the gorge.

I wonder how many of us would take on the Grand Canyon if:

1. Nobody could tell you what is around the next bend, and it might be a 40-foot waterfall with nowhere to portage on either side of the river.

2. Two or three times a day (every day), you had to get out of the boats and carry heavy burdens around the rapids over treacherous boulder fields. Powell estimated that each man had to carry 800 pounds of gear around each bad rapid.

3. Periodically, you had to stop to use hand saws to make new oars or paddles from whatever driftwood you could muster up, some from miles into lateral canyons.

4. You had to carry the boats or rafts around the larger rapids. It took four strong men to lift one of Powell’s wooden boats.

5. Your food would consist of unleavened bread, semi-rancid bacon from which the mold has been sliced off, dried apples, and coffee. And even that fare would have to be severely rationed.

6. You had no life preservers.

7. You had to drink right out of the Colorado River.

There are people who would do this, of course. But not many. They are the same kind of people who run from Death Valley (282 feet below sea level) to the base of Mount Whitney and then climb Whitney (14,505) without stopping. That’s a 135-mile run. It’s called the Badwater Ultramarathon. It usually takes place in the later summer when the temperature in Death Valley can be 120 degrees. It operates by invitation only. Each year 100 people do it, or at least start it. My invitation, I guess, was lost in the mail.

[Sorry, I had to take a nap after writing those sentences!]

John Wesley Powell is one of my heroes. He never let his disability stop him from doing anything he set out to do. He was uncomplaining. And he didn’t have to help with the portages! He respected Indigenous people, learned their languages (took down and classified their languages!), traveled among them without a military escort, regarded them simply as other worthy human beings living according to a very different software, and throughout his career, Powell advocated fair treatment for Natives. He was, for a few years, America’s first water czar. He supported a campaign of industrial irrigation in the West beyond the 100th meridian. Still, he warned the nation’s boosters that water scarcity would be the defining and limiting factor in Western development (for which he was booed and shouted down). He recommended a new homesteading system that would prevent innocent families from trying to make a living on 160 acres in a place without a river or creek where it rained only three or four inches per year. He created the template for the USGS quadrangle maps we all buy when hiking in a remote place.

Would John Wesley Powell have been OK with seeing his beloved Glen Canyon dammed, the resulting giant reservoir named Lake Powell, in his honor? It is impossible to know the answer to this question. I can make the case for yes or no. But he surely would have felt a great sense of loss that Glen Canyon was inundated by the US Bureau of Reclamation, endangering Rainbow Bridge and drowning the magnificent Music Temple he explored in early August 1869.

The other books I am reading about Powell are also excellent. I am rereading Edward Dolnick’s Down the Great Unknown: John Wesley Powell’s 1869 Journey of Discovery and Tragedy Through the Grand Canyon. It’s solid in every way, but there are some very quirky similes. Last week, I read John F. Ross’s The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell’s Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West. And I’ve just begun to reread Wallace Stegner’s classic Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. There is also a good account of the 1869 journey in Kevin Fedarko’s The Emerald Mile: The Epic Story of the Fastest Ride in History Through the Heart of the Grand Canyon.

Meanwhile, on eBay, I purchased (at a ruinous price) a first edition of Powell’s 1875 narrative. It will arrive next week. The illustrations are magnificent. There is a backstory to that involving Scribner’s publishing house, but Powell’s journeys in Canyon Country are blessed with some of the finest illustrations in the history of exploration.

One of my goals is to get myself (and friends) to the exact spot from which the great Thomas Moran (employed by Powell) made sketches for what would be his epic painting of the Grand Canyon. The diminutive Moran said “It was the most magnificent sight of my life.” I’ve never been to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Soon. But the list of the sublime places I have never been merely in the states of Utah and Arizona would fill a Moleskine notebook.

I’ve spent plenty of time in the Southwest. Utah alone has five National Parks: Zion, Bryce, Arches, Canyonlands, and Capitol Reef, not to mention two of the largest (and once again controversial thanks to the 2024 election) National Monuments: Grand Staircase Escalante and Bears Ears. You could spend years exploring any one of these federally protected places. There are probably a dozen more landscapes in Utah that would be National Parks in any other state. My recent reading has whetted my appetite for serious exploration of the Four Corners region.

Two Colorado Plateau writers (two adventurers) particularly appeal to me: Powell of the 19th century and Edward Abbey (1927-1989) of the mid-20th. But now I also want to read Clarence Dutton’s 1882 Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon, which is said to be so scientifically insightful and well written that it has achieved status as a classic of Western writing despite the geology.

It never ends! Edward Abbey alone wrote more than 20 books, depending on how you count.

Major Powell did everything in his power to warn us not to over-allocate the rivers of the American West. He urged us to subordinate state pride and engage in comprehensive watershed management of the Colorado and other rivers. He called them Watershed Commonwealths and made a beautiful map to delineate them. Now that we have entered what we are told is a permanent water crisis in the Southwest (not enough water to satisfy all users, even before global climate change), his realism has been vindicated. We did not listen then. Perhaps we are ready to begin listening now. That starts with Powell’s monumental (and radical) Arid Lands Report from 1878, one of the most radical books ever published by the US Printing Office.

You can knit Powell and Edward Abbey together by reading Abbey’s Down the River, wherein he and his friend Ralph Newcomb floated Glen Canyon just as the Bureau of Reclamation was destroying it with one of the largest dams in the world.