Amazing Engineering Grace: The Brave New World we take for granted. Clay reports from the Chunnel — traveling between England and France.

I write these words from under the English Channel! My daughter and I are taking the train today from London to Paris. I studied at Oxford for four years, long ago, and went to the Continent several times by ferry, but I have never taken the Eurostar Tunnel (Chunnel) until today. The idea of traveling under the 23-mile English Channel is mind-blowing from many perspectives. It’s the kind of stunning engineering feat that we now take for granted. It’s also a symbol of the peacefulness of post-World War II Europe. Why else would Great Britain, which has always had a sense of stubborn detachment from the Continent, create a chute through which an adversary could thrust an invading army at the Cliffs of Dover?

Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt (in Richard II) called the island of England:

“This fortress built by Nature for itself

Against infection and the hand of war,

A precious stone set in a silver sea

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands.”

It has been an astonishingly successful moat. When we speak of Europe, it is never quite clear whether that includes Britain. The English Channel has had enormous, almost incalculable, symbolic value, signifying “not truly Europe.”

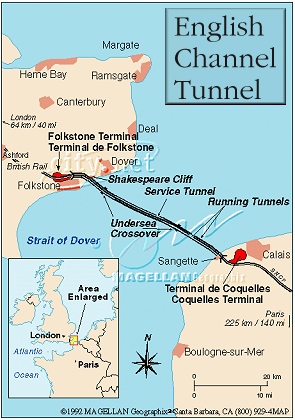

The Chunnel was completed in 1994 over the stiff objections of nativists of both nations, particularly in Britain. Both the UK and France can flood the tunnel in the event of an existential threat to their national security. The English Channel has saved Britain from Continental invasion a number of times in its history, from Julius Caesar’s legions (55 BCE), Napoleon (1802-1805), and most recently in 1940, when Adolf Hitler, having already overrun northern Europe, had no navy capable of crossing the Channel with an invading army.

The Chunnel is the third longest railway tunnel in the world, a miracle of modern engineering. It was constructed late in the last century when Britain was moving toward fuller integration into the European community. I doubt that it could be built today in the era of Brexit and the First World’s populist backlash against a borderless world.

When my friend Douglas and I crossed from Britain to France by ferry for the first time decades ago, we learned in a hurry how unsettled the English Channel can be. He retched over the rail into the sea, and I had to breathe as hard and deeply as possible to avoid throwing up myself. By the time we landed at Calais, our faces were as green as an Edvard Munch painting.

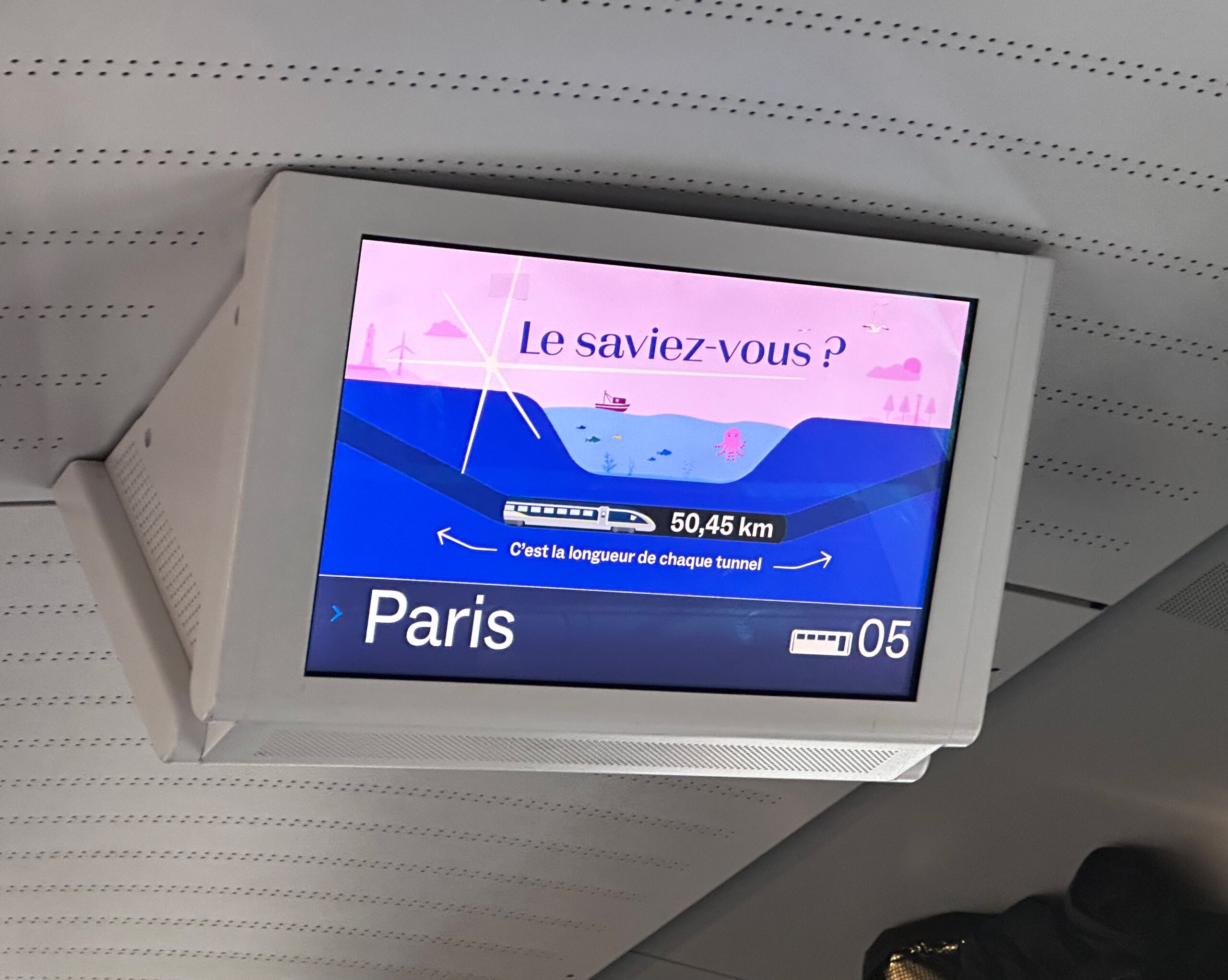

We are now submerged in a 31.35-mile tunnel below the 23-mile-wide English Channel from Folkestone, England, to Calais, France. At its lowest point, the tunnel is 246 feet below the sea bed and 377 feet below sea level. When I try to imagine how they built it, I am awash in sheer admiration for us homo sapiens, a hairless primate with opposable thumbs. A friend calls humans “an invasive species with tools.” To which I say, thank goodness. What would life be without a pair of pliers or a flashlight? Thomas Jefferson’s 2-year-old daughter Lucy died of whooping cough (1785), and George Washington died of strep throat (1799). Give me antibiotics, jet engines, escalators, Ziplock bags, and aluminum foil. The Brits called it al-u-MIN-ium foil for reasons best known to themselves and the editors of the immense Oxford English Dictionary, one of the world’s supreme intellectual achievements.

They talked about a tunnel below the English Channel when I was a graduate student at Oxford. There was fierce debate. Even those who accepted that the Chunnel would not represent a serious security threat argued that it was unwise for Britain to integrate itself, even symbolically, into the European community.

Visionaries began imaging a tunnel under the English Channel as far back as 1802 when Thomas Jefferson was settling into his first term as president of the United States. A French mining engineer, Albert Mathieu-Favier, proposed a tunnel illuminated by oil lamps where horses would draw carriages. He reckoned there would need to be a human-made island in the Channel to permit the changing of horses midway.

Today, my daughter and I are sitting in Coach 5 (second class) in comfortable seats with about as much legroom as an airplane. Now that we are well underway, young people (and men who want a steady supply of beer) careen by us towards the club car. My daughter is dozing. I am poaching electricity from under my seat and internet from … well, somewhere.

I am amazed that I can be sitting in a secure and comfortable coach traveling 180 miles per hour (!) between two of the most influential national capitals of the world, typing on a laptop computer (itself a technological miracle if you think about it), and effortlessly downloading data from a range of websites, responding to a series of emails, posting photographs and videos, texting friends in another hemisphere and getting their replies (if they are up at this ungodly hour in the U.S.) within seconds, not even minutes. It’s astonishing; of course, we have come to take it all for granted. When the internet goes down on the train, even for a few minutes, there is outrage from the passengers, who now seem entitled to full connectivity wherever they happen to be on the planet.

My daughter booked our tickets online and paid for them with an effortless electronic transfer of funds. We checked in and passed through security on her smartphone. Her heart rate (not to mention our elevation and our latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates) is being monitored with her Garmin “watch.” Most people on board — those who are not sleeping — are glued to a smartphone or a laptop. Some are watching movies or popular television shows. Some are playing games. A few people are reading books; some are actually printed books.

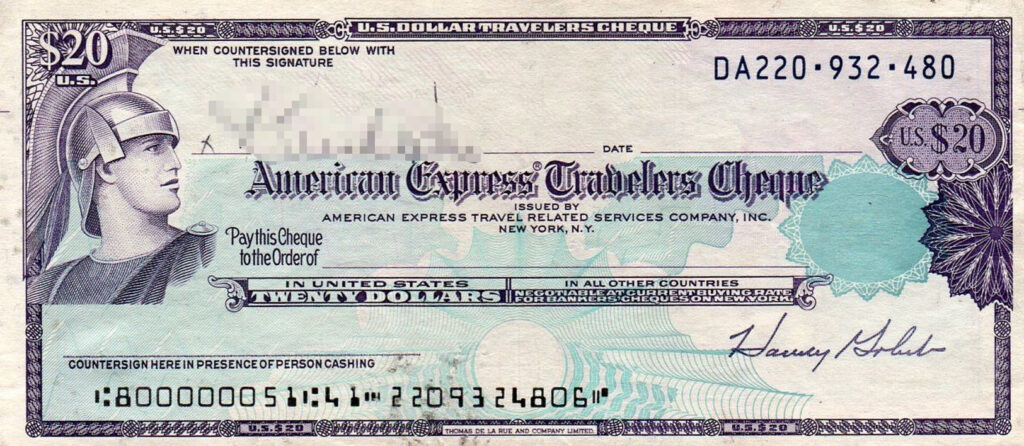

As I was leaving the United States late last week, my daughter advised me not to bring any currency. Europe — even Great Britain — is now essentially cashless. Last evening, our taxi driver in Oxford did not blanch when we asked if we could pay by card. In New York, Boston, or Washington, D.C., one is often hassled by taxi drivers who refuse to use the credit card systems they are required by city code to employ. So far we have purchased museum tickets, train tickets, meals, snacks, drinks, books, cards, medicine, and notebooks — all without ever reaching into our pockets. I have a few U.S. twenties in my wallet but no English pounds, no Euros. I doubt I will ever put a piece of printed currency into anyone’s hands in the three countries (England, France, Switzerland) we are traveling.

I’m old enough to remember traveler’s cheques. You’d go to the bank in your hometown and convert funds into a clunky book of blank checks, which were somehow regarded as more secure abroad than your own country’s currency. At every hotel you slept in, you’d try to pay with those checks or stand in line at a Currency Exchange to transfer U.S. funds into French francs, German marks, Italian lira, or Yugoslavian dinars. Then came the first ATMs. Today, you merely stretch out your wrist so your smart watch can transfer electronic money from your home account to a florist shop near the Champs Elysée in Paris. Beep.

And — again — we take all this for granted.

It’s easier to travel the world today than at any previous time in human history. I shudder when I think of Thomas Jefferson crossing the Atlantic for a whole month (July 1784) in a boat so small that it makes this modest railroad coach seem like a five-star hotel, with a cabin so cramped that he and his daughter Martha (then 11 years old) had to crawl into it like a cave. They had to bring their own food and good wine because it was Jefferson. That monthlong voyage was regarded as a fast transatlantic transit in that era.

When John Adams crossed the Atlantic on the 24-gun frigate Boston with his son John Quincy in February 1788, they were menaced by a British warship; a bolt of lightning struck the mast, killing one sailor; and the storms they passed through were so violent that even the seasoned crew was seasick. In a second encounter with a British ship, Adams — the future president of the United States — was seen brandishing a musket. At one point, a cannon exploded on the deck, injuring an American sailor so severely that he had to have his leg amputated — with a hand saw — without anesthetic of any sort. He later died. When the ship finally reached the French port, the winds were so strong that it had to wait several days before it could dock. Just remember how annoyed you are when the captain of your airplane comes on the intercom to say he has good news and bad news: you are 22 minutes early, but your gate is currently occupied, and it should be only a couple of minutes (liar) before you can dock.

In his post-presidential autobiography, Adams said that he had six near-death experiences on that 1778 Atlantic crossing. Adams was something of a drama king, but he seldom exaggerated. Had the famously stoic and understated Jefferson made the same journey, he would have written something like, “Our voyage was not without certain difficulties.”

We began today in my daughter’s flat in central Oxford. Lugged out two large suitcases, my book bag and computer bag, plus her Euro backpack, 20 minutes to the Oxford train station. The train from Oxford to Paddington Station in London took about an hour, with just two stops. Then we took two different subway (tube) rides under the city of London from Paddington to St. Pancras Station, where we went through security twice (thanks, Brexit!) before boarding the Eurostar, which took us nonstop to Paris in just under two hours. There, fatigued from a dawn start, we foolishly stood in line for an hour to get a taxi to our hotel near Notre Dame Cathedral, where our rooms — miraculously — were ready and made available to us.

I arrived in London two days ago, less bleary than usual. I got through passport control and customs (an entirely electronic transaction) without more than a few minutes delay. Amazing. There are times in the USA when it takes well more than an hour to get through passport control. I walked a long way with my luggage — a second large suitcase filled with things my daughter requested — to the central bus (coach) station. I bought a ticket (26 pounds sterling) to ride a coach to Queens Lane in Oxford, about five minutes from my old Oxford College Hertford and 15 minutes from my daughter’s college, Lincoln. Oxford is a university with 36 residential colleges, each with a complete set of professors, a library, a dining hall, a chapel, and some students’ rooms. I rested in her flat for 45 minutes, took a shower, and we hit the streets. We visited the Pitt Rivers Museum just north of the center of Oxford looking for a friend’s photograph exhibit, walked past a number of my old haunts, enjoyed a special rare books tour of books by and about Pembroke’s most famous alum, Dr. Samuel Johnson, one of my heroes, drank a pint of beer at a mutually-favorite pub (where Bill Clinton didn’t inhale), ate dinner at an excellent Indian restaurant, and called it a (first) night.

The Chunnel is an anti-climax when you actually pass through it by train. At 185 mph, it takes approximately 12 minutes to travel from the island of Great Britain to the European continent. I feel a little cheated. The Eurostar makes no dramatic announcement as you dive under the sea: ho-hum, you are in one of the modern world’s engineering wonders; the snack car is now open in car 14. No graphic display, no reminder that you are “under the sea,” no announcement that you have entered another nation that speaks an entirely different language. If you dozed off, you’d miss the experience altogether. You can’t see anything outside the train window, of course — though in your pre-trip imagination, you expect to see fish, eels, and the wrecks of all the ships that have gone down over the millennia, like swimming in an aquarium.

I’m going to push “send” from the moving train. Somehow, my signal is going to fly up to a satellite, and it will be hurtled at the speed of light to a server somewhere in America, where it will find its way to my editor in New Mexico. And then to a website — and you.