In preparation for a cultural tour of Cuba Clay is leading later this month, he came across a surprising connection between John Steinbeck, Adlai Stevenson, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

John Steinbeck had always been a Stevenson man. He admired Adlai Stevenson as that rarest of things: an intellectual politician, a well-read, genteel, and cerebral man who put himself into the political arena. Steinbeck supported Stevenson’s two presidential runs — 1952 and 1956 — and he was in the Stevenson camp even in 1960, when John F. Kennedy won the Democratic nomination in Los Angeles.

JFK appointed Adlai Stevenson (1900-1965) to be America’s ambassador to the United Nations. He served in that capacity from 1961 until his death on July 14, 1965. At the time, the U.N. was still an essential world organization during rising unrest and decolonization in the underdeveloped world. And at the height of the Cold War.

Stevenson gave his most important U.N. speech on October 25, 1962, at the gravest moment of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In his famous address — primarily written by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. — Stevenson laid out the facts of the USSR’s secret installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba, outlined and decried Soviet denials and deceptions, and expressed the United States’ determination to force the removal of the missiles no matter what it would take (up to and including nuclear war). Near the end of his speech, Stevenson directly confronted the Soviet representative Valerian Zorin:

Stevenson: All right, sir, let me ask you one simple question: Do you, Ambassador Zorin, deny that the USSR has placed and is placing medium and intermediate range missiles and sites in Cuba? Yes or no. Don’t wait for the translation, yes or no?

Zorin: This is not a court of law, I do not need to provide a yes or no answer. …

Stevenson: You can answer yes or no. You have denied they exist. I want to know if I understood you correctly. I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over, if that’s your decision. And I am also prepared to present the evidence in this room.

Of course, Zorin refused to answer, but no one in the room doubted that Stevenson was stating the truth.

President Kennedy was impressed by Stevenson’s performance. He sent the ambassador the following telegram:

DEAR ADLAI: I WATCHHED YOUR SPEECH THIS AFTERNOON WITH GREAT SATISFACTION. IT HAS GIVEN OUR CAUSE A GREAT START … THE UNITED STATES IS FORTUNATE TO HAVE YOUR ADVOCACY. YOU HAVE MY WARM AND PERSONAL THANKS.

The Cuban Missile Crisis (the “13 days“) ended peacefully when the U.S. and the USSR cut a deal. Russia agreed to remove the offensive missiles but refused to permit U.N. inspectors to monitor the removal. In exchange, the U.S. pledged not to invade Cuba (ever), and secretly, the U.S. agreed to remove its own nuclear missiles from Turkey near the border of the Soviet Union. Secretary of State Dean Rusk famously quipped, “We’re eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.”

Actually, both fellows blinked. John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev both stood up to the loud, rude, and insistent military hawks in their administrations and worked out a peaceful compromise to the crisis. This was as close as the world ever came to nuclear holocaust. The hawks on either side could not be mollified. Curtis LeMay, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, browbeat his Commander in Chief, JFK, during the ExComm meetings in the White House. His view was that this was the perfect excuse to rid the world and Cuba of Fidel Castro, that nuclear war with the Soviets was inevitable, and this was the most advantageous time to get it over with, and that any American conciliation would represent a humiliating defeat for the United States and the western alliance. At one point, he reportedly banged his hands on the table in the conference room and accused JFK of treason. JFK, just 45 years old, the youngest elected president of the United States, had the courage to resist calls for air strikes against Cuba, followed by an actual invasion that would almost certainly have triggered a nuclear war.

Khrushchev faced similar pressures, but he chose to step back from the brink.

It is interesting to note that both of these leaders were removed from the arena within two years. Khrushchev was deposed in October 1964 and forced into private life; JFK was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

We Interrupt This Broadcast: “John Steinbeck Has Been Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

What makes this episode interesting is that as the Steinbecks were watching TV on the morning of October 25, 1962, to see, Steinbeck wrote, “if the world was still turning” (and no doubt watch Stevenson’s speech), that they heard, for the first time, (on television!) the words: “John Steinbeck has been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.” Steinbeck’s third wife, Elaine, was so thrilled that she took her pan of frying bacon off the stove and put it into the refrigerator. Then the phone began to ring!

Whether Steinbeck could any longer concentrate on Stevenson’s speech on that Thursday in 1962 or even think about the missile crisis is unclear.

Steinbeck was a great and seemingly indefatigable writer of letters. I would have thought that he would have written to his friend Adlai that day or soon thereafter to congratulate him on the greatness of his speech and confrontation with representative Zorin and to express joyful irony in being awarded the most significant prize a writer could imagine amid a world crisis so grave that few people had time to hear of his literary triumph. That kind of self-deprecating irony was standard fare with Steinbeck. I have consulted the standard book of Steinbeck’s correspondence — Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, 908 pages — but there is no such letter in the collection. This points to a serious Steinbeck studies problem. I don’t know how many letters Steinbeck wrote in his lifetime (1902-1968), but it is many times more than those encased in A Life in Letters. There are rumblings of a complete and definitive edition of Steinbeck’s letters. If my friend Russ Eagle were not in his 60s, if he were 30 with the scholarly confidence he has today, he would be the perfect individual to undertake so essential and daunting a task. Russ has the intellectual discipline and dedication to detail required by such a project. But for now, we cannot be sure whether Steinbeck wrote a post-Cuban Missile Crisis-Nobel Prize letter to Stevenson. The Stevenson papers are largely at Princeton University, and they have, so far, not been digitized.

Steinbeck did write to Stevenson on November 20, 1962, as the world settled back into uneasy peace, asking for help in writing his Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

“The whole idea fills me with horror. Then it occurred to me that you are undoubtedly the best speaker in the world; that having made so many speeches, one more would mean nothing to you. I’m sure you wouldn’t mind making this speech for me. And I’m sure the Academy [the Nobel Academy] would be more than pleased.” Steinbeck wrote.

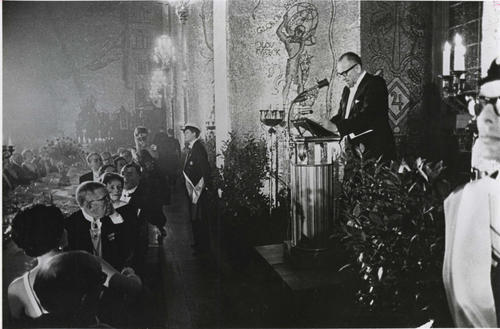

Steinbeck was on his own. He agonized over his acceptance speech. He hated public speaking, shunned public appearances, and feared the negative effects of celebrity. “I wrote the damned speech at least 20 times,” he wrote his friend Carlton Sheffield. “I tried to make it suave and diplomatic and it was a bunch of crap.” In fact, it was a masterpiece, one of the best by an American writer.

In the speech, delivered in Stockholm on December 10, 1962, Steinbeck included a powerful passage about the terrors of the new Atomic Age:

“Less than fifty years after [Alfred Nobel’s] death, the door of nature was unlocked and we were offered the dreadful burden of choice. We have usurped many of the powers we once ascribed to God. Fearful and unprepared, we have assumed lordship over the life or death of the whole world — of all living things. The danger and the glory and the choice rest finally in man. The test of his perfectibility is at hand. Having taken Godlike power, we must seek in ourselves for the responsibility and the wisdom we once prayed some deity might have. Man himself has become our greatest hazard and our only hope.”

— John Steinbeck.

This is magnificent. It needs to be read in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis, only one month previous, the world stepped to the brink of annihilation, with a death count that would have numbered in the hundreds of millions. If either JFK or Khruschev had failed to blink, failed to defy the military hardliners, October 1962 would have been the most pivotal day in human history. Not even Arthur Schlesinger (or Stevenson) could have written this brief passage so perfectly. Sometimes, we forget how serious a man John Steinbeck was and how superb a writer of English prose. Steinbeck believed that writers (and other artists) must explore the human condition unblinkingly and ennoble the human project with stories (our oldest art form), insights, warnings, and calls to enlightenment.

Few people alive today can imagine the terror of October 1962. The Cuban Missile Crisis provoked hundreds of thousands of Americans to build bomb shelters in their backyards. The stone-sober Robert McNamara left a White House ExComm meeting on a beautiful Saturday evening at the height of the crisis (October 27, 1962) to get a bit of much-needed home rest. He later said:

“I was leaving the White House whatever, around dusk, to go back to my office in the Pentagon. It was a perfectly beautiful night, as fall nights are in Washington. I walked out of the President’s Oval Office, and as I walked out I thought I might never live to see another Saturday night.”

I’d give anything to be in the Steinbeck residence at Sag Harbor, Long Island, on October 25, 1962. We need all of his letters to be collected and made available online. Just as his writing journals are essential to understanding his craft and methods, so his collected letters would represent an outstanding window into those 66 years, 1902-1968. He was in the arena through it all: World War I (East of Eden), the Great Depression (Of Mice and Men; The Grapes of Wrath), World War II (Once There Was a War; Bombs Away; The Moon Is Down), the war’s aftermath (Cannery Row), the Cold War (A Russian Journal); America’s postwar boom and materialism (Travels with Charley, The Winter of Our Discontent) and Vietnam (his dispatches from South Vietnam 1966-1967).

Those who dismiss his greatness — including a vicious New York press in the aftermath of the Nobel Prize announcement — have perhaps forgotten his range, scope, depth, and capacity to embody the times and places in which he lived.