Over the Christmas holidays, because I was alone this year, I decided to read all the journals of Lewis and Clark, John Ordway, and Patrick Gass for the return journey of the Corps of Discovery, from March 23 to September 23, 1806. If Whitehouse kept a journal for this portion of the trek (probably), it has been lost. I read the captain’s first, then Patrick Gass. I wanted to see what Gass wrote in isolation, to try to get a better sense of him as an individual, not just as the expedition’s carpenter.

First, what a joy! I took extensive notes, traded emails and texts with my esteemed friend David Nicandri about the things I was learning or pondering, and I made lists. There is nothing more satisfying to me than having ample time to give to a project of this sort. I’d read for a couple of hours, type out some notes, then turn to something else (reading Dostoevsky, baking a batch of cookies, looking for some book in my home library). And later, another round of Patrick Gass. It has been blizzard time on the plains of North Dakota, so I had plenty of reason to stay indoors with my books and notebooks.

Second, I thought I knew this story well, but by reading the journals consecutively and with great care, I discovered things I did not know, or (alas) once knew and forgot. To discover something new in Lewis and Clark, if only for oneself, after years of study, is pure joy. Here are just two examples.

I knew that when Clark took his contingent to Camp Fortunate (now under Clark Canyon Reservoir), “the most of the Party with me being Chewers of Tobacco become So impatient to be chewing it that they Scercely gave themselves time to take their Saddles off their horses before they were off to the deposit.… I gave to each man who used tobacco about two feet off a part of a role.” Several journal keepers indicate that the men suffered far more from running out of tobacco — at Fort Clatsop or shortly thereafter — than running out of whiskey on July 4, 1805, at the Great Falls.

But now this. When (June 18, 1806) Sergeant Gass took a couple of men to the Lower Portage Camp to check on the cache there and the status of the white pirogue, which had been left behind back in June 1805, the men with him opened the cache, saw that it was intact, extracted some tobacco from the varied things that had been deposited there, and then re-covered the cache! In other words, their quest was simple: tobacco.

It is details like this that humanize the great transcontinental expedition.

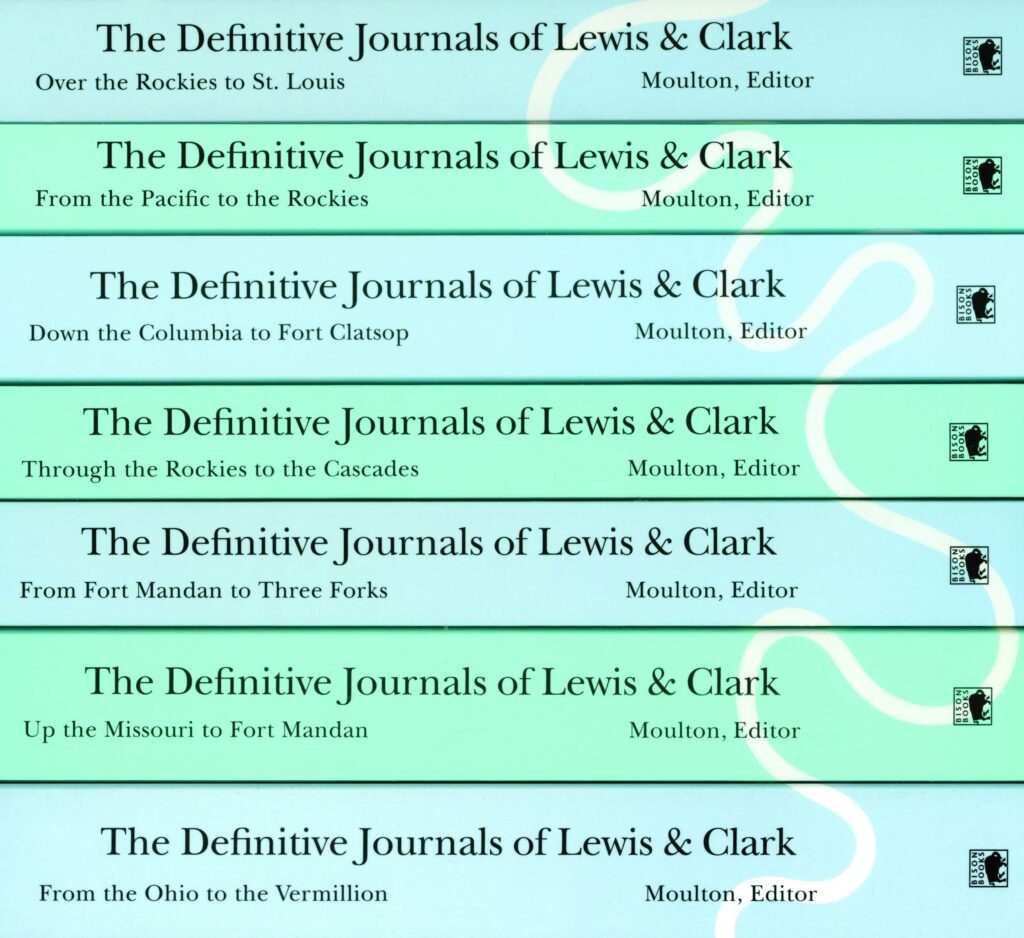

We all owe Gary Moulton immense gratitude for the hard and painstaking work he undertook on behalf of American history, in gathering into one set of volumes all of the extant journals of the expedition, not just establishing the authoritative text, a common resource for every serious student of Lewis and Clark, but providing thousands of accurate and helpful annotations, some of which must have cost him days or even weeks of research and communication with the experts he attracted to the project. Plants, minerals, names of Native American tribes, names of individuals, the correct Native orthography for things the captains garbled in their transcriptions, campsites, geographic landmarks, minor tributaries of modest tributaries of the great rivers, medicines, notations on scientific instruments, corrections or affirmations of minor details they included for the animals they described. Professor Moulton did all this for all of us. Now we owe it to him and to ourselves to read the journals in his thirteen splendid volumes in the way he has presented the great story to us. There is, as I am rediscovering, so much to learn — or relearn.

Here’s another great moment. We all know that the expedition was essentially bankrupt when it turned back towards the United States in March 1806. Lewis said that everything they now had to trade with Native people — for firewood, food, ferrying services, horses, guidance — could be contained in two handkerchiefs. It is so important to keep this in mind as we think about the 1806 return. They were about to make a 3,500-mile journey without “money.” Lewis had not had the opportunity to cash in his universal letter of credit in one of the Columbia River’s bays to resupply the expedition with trade goods. Desperately needing an additional canoe, on March 17, 1806, Lewis had to give up his last military dress coat to close the deal with the canoe’s owner. With more than a little pique, Lewis wrote, “I think the U’ States are indebted to me another Uniform coat, for that of which I have disposed on this occasion was but little woarn.” All this I remembered. He collected, by the way, after he returned to Washington, D.C.

On June 22, 1806, on the western base of the Bitterroot Mountains, delayed by deep snow and the obscured Lolo Trail, the expedition’s focus was in getting enough food to feed everyone. The hunters were returning empty-handed. Then this by William Clark: “we gave whitehouse a fiew beeds which I unexpectedly found in one of my waistcoat pockets to purchase the fish.” This must have been a joyful moment — a handful of beads carelessly thrust at some earlier and more prosperous moment into the pocket of that vest, forgotten, but now discovered at a time of real need. It’s like the joy we feel when we find a $20 or $100 bill in the pocket of a sports jacket or an old purse. Free money! The expedition left St. Louis in May 1804 with at least fifty pounds of beads. Now they were reduced to a “fiew beads” scrounged out of an unlikely place.

But now those few beads helped feed the expedition.

From Gass we learn that not every member of the expedition was regarded as a hunter. We learn, if Gass understood things correctly, that Clark was not entirely sure when the party split up at Traveler’s Rest that he would float the Yellowstone. We have access to David M’Keehan’s intelligent, useful, occasionally erroneous annotations of Gass’ narrative. In other words, M’Keehan, best known for his vicious 1807 newspaper attack on Meriwether Lewis, was not invariably snarky!

Without the herculean labors of Gary Moulton, this sort of intense study would have been much more difficult, and some of it simply impossible.