As I look to the start of the new year, Thoreau’s 1854 classic still deeply challenges and inspires me.

Bismarck, N.D. — December 26, Boxing Day. Alone on the northern plains, I have the whole day before me and several important books to read. The principal task of the day (how can I call it a task?) is to read much of Thoreau’s Walden. Yesterday and on Christmas Eve, I read “Economy,” the first and longest chapter of Walden and the one that causes the most frustration. Here’s why. If you add up all the passages in that opening chapter about Thoreau building a cabin near the shore of Walden Pond, they occupy only a handful of pages, maybe four or, at most, five. The rest is “argument” in several senses of the term. Most readers of Walden chafe at the complexities of “Economy” and just want Thoreau to build the damn cabin and start observing Nature. Ah, but Thoreau is not in any hurry to do that.

So what is he asking of us? Above all, he wants you and me to look closely at our lives — along Socratic lines, on the principle that the unexamined life is not worth living. Thoreau wants you and me to ask ourselves what we surround ourselves with and at what cost. And “cost,” it turns out, is not merely the number of dollars you had to lay out for whatever it is, the number of days you have to work for your _______ (boat, home theater, lake cottage, Mercedes, jet ski, wedding ring, etc.), but for the larger and more important “costs” — the opportunity cost (what else might you have done with your finite time and money), the cost to the poetry in your soul, the cost to your happiness, the cost to the principle of distributive justice, and (now) the cost to the planet Earth.

I’ve been doing just that. I’ve been a maximalist, not a minimalist. My large house, in which I live alone 97% of the time, is stuffed to the gills with books, gadgets, cameras, foodstuffs, appliances, furniture, souvenirs from my travels, clothes, boots, tools, costumes, etc. Twenty years ago, I bought a big space (my house) and filled that space to the choking point.

So, in hosting annual humanities retreats at a lodge west of Missoula, where we talk about “costs” for days on end, it is more “do as I say, not as I do,” or rather “do as Henry Thoreau did, not as I do.”

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. … In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness.”

Walden, Henry David Thoreau

The dis-order of my lifestyle (if it can even be called that) is such that I often cannot find what I need (though I know it is here), and therefore what Hamlet calls “enterprises of great pith and moment” miscarry because I cannot assemble all the necessary ingredients in a timely fashion. I’m not a hoarder, exactly, and I don’t think I am quite ready for an intervention, but the over-stuffedness of my life has reached a now-or-never point. Is this how I am going to trudge out of the last 20 years of my life, or do I have it in me to downsize, repurpose, prioritize, organize, and de-acquisition?

That’s one question.

The other question is related: Can I stop acquiring new things? Amazon.com has made it so easy to search, select, and push “place your order” that I don’t even have to get in the car and drive to a bookstore or a sporting goods store to keep filling my space with more things than any responsible person should have: abundance and super-abundance. If you had to pull actual cash out of your pocket to pay for all these extravagances, well, you wouldn’t.

Because I see the problem — I could provide a score of anecdotes that indicate how seriously things are out of control up here in my subdivision house with a three-car garage that is nothing more than a storage facility — I am particularly ripe for the wisdom of Henry Thoreau — and “Economy” is the best anthem to simplification, deliberateness of purchase, and knowing when abundance becomes a choke hold on the soul.

So here is what I am doing, however picayune it may seem from the outside. I am getting rid of five things per day through 2025. Yesterday, I de-cluttered my kitchen, or part of it, because I have more pots, dishes, gadgets, and “spices” than will fit in the lavish cupboards. Yesterday, I put approximately 350 items into boxes. They go first to the garage. I’ll keep them there for a few months, and then — if nothing propels me to find something in one of those boxes — I will take them to a thrift store.

I have been getting rid of five books per day, too. So far, so good. I have not had to cut into any tendon or muscle yet. But that day, alas, is coming.

There are three reasons I write about all of this. First, I believe Thoreau is precisely right that the American quest for more and more material things, including things that confer prestige, is killing us, the poetry in us, and our souls. We are overweight, overfed, and overextended. We are addicted. The malaise of America — as seen in our broken national politics and social structure — is not finally about the Second Amendment or the Fifth, not about our national political leadership. It is about the glut that has backed up the plumbing of our souls. In other words, even though Walden was published in 1854, it speaks to us right now and in the best possible way. Thoreau gets the diagnosis right, though he would be appalled by how much worse things are in our time than in his.

Second, Walden repays reading again and again throughout a lifetime. Walden delivers. I’ve read it two dozen times by now, some parts of it more, and it has never failed to knock me off my legs and inspire (force?) a re-evaluation of my life. My job as a humanities scholar is to help others learn to appreciate the book for all it can do for us individually and perhaps as a society. Thoreau doesn’t always make it easy. He annoys all of his readers some of the time and some of his readers all the time.

Third, given my Airstream travels (a small experiment in minimalism) and the fact that I am about to observe an important birthday (it’s the seventh inning, maybe the bottom of the eighth), reminds me that I don’t have that many changes left to build the life to which I have long aspired. I intend to see this Thoreauvian experiment through. I believe my life will be better in every way one year from now if I continue my climacteric resolutions. Which are these:

My Thoreauvian Experiment

“I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor.”

Walden, Henry David Thoreau

- Get rid of at least five things a day through 2025. (Since I travel a great deal, this will mean some flurries of downsizing when I am home.)

- Walk no less than 25 miles per week and much more if possible. Nothing is as essential in moral reform as long walking.

- Wait 24 hours before pushing “send” on books I “want” from Amazon.com. I have discovered that if I wait just 24 hours, many of my impulsive purchases slip quietly away. I reckon such a move will save several thousand dollars this year, and of course, it matters in the downsizing plan. If you get rid of 10 books but order 20 more, you are only worsening the problem.

- I will watch no (zero) cable news (MSNBC, FOX) in 2025 unless we are directly involved in a gigantic earthquake or war. If the Yellowstone caldera blows, I’ll tune in (assuming I am not petrified in ash like the citizens of Pompeii). I’ll turn on CNN; otherwise, I will read my daily news feed on my smartphone and keep up with the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and The New York Review of Books. But no cable commentary.

- Finally, I have pledged to write one real letter (often but not always printed on paper and inserted into an envelope) every day this year. Not pro forma letters, but genuine letters worthy of being called correspondence.

I’m inspired in this by one of the finest sentences in Walden, that repository of hundreds of great sentences, and passages:“I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor.”

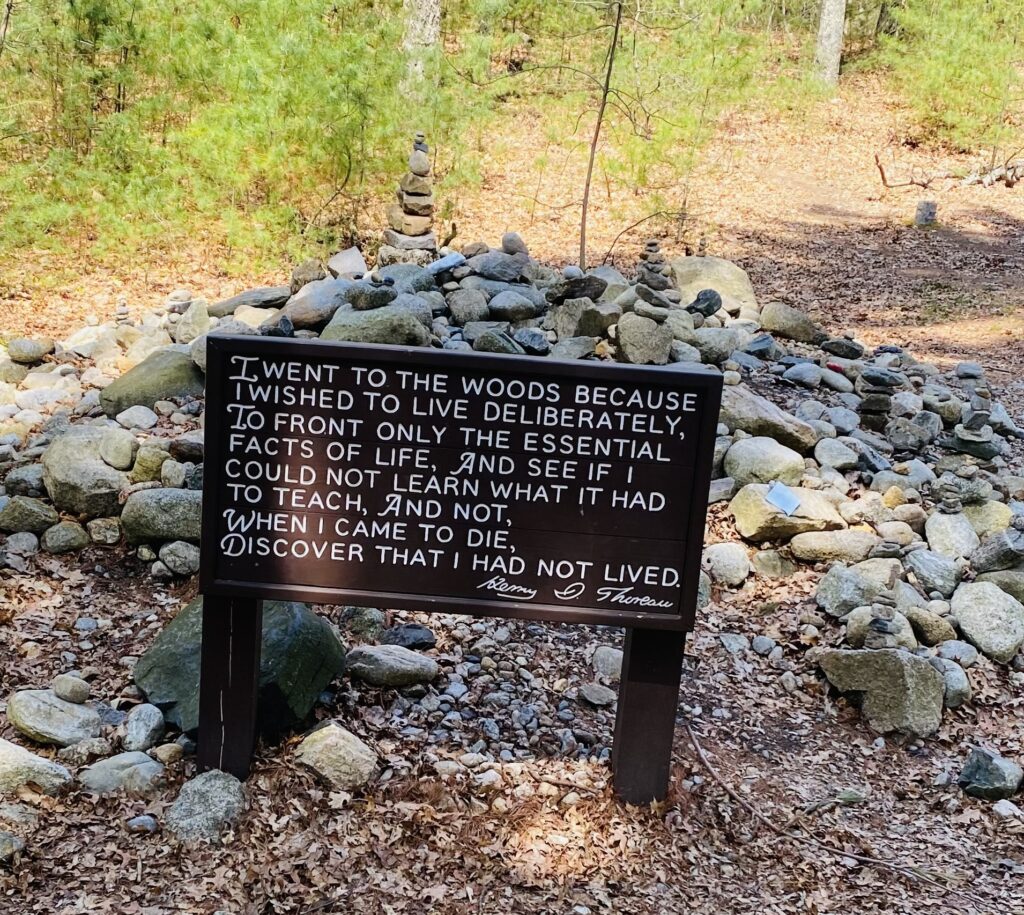

Will I backslide? Of course. But I have long since reached an unsustainable plateau in my life. I’m putting Thoreau on notice, too. He says, in the most famous passage of Walden, that he went to the woods to live deliberately, to suck out all the marrow of life, to reduce it to its lowest terms, and then to report. He says it may prove to be a failed experiment, in which case he promises to divulge that to the world. But he makes it clear that he believes the experiment will be a great success, that his soul will blossom in unprecedented ways, and that he will be able to recognize the upgrade in quality of life that comes from modesty or minimalism. Thoreau did not want to die, only to “discover that I had not lived.”

That’s my greatest fear. To discover that I had not lived, that I was content to see the world in AM when it was FM at least, and maybe X-ray, infrared, cosmic rays, and more. To discover that I lived mostly as an automaton and went through life without actually living it to its fullest. That I settled when the universe was right in front of me.

I heartily and sincerely recommend that you stop and take the time to read Walden in the next few weeks. Don’t be put off by his paradoxes and his occasional righteousness. Do the experiment: calculate how much stuff you have (and its “costs”), how much stuff you actually need, and how much of what you have is just collecting dust — or, much worse, choking your soul. Then, either shrug and go on with a life you approve of or take careful steps to move in a Thoreauvian direction towards what he calls a “life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust.”

It is, says Thoreau, a new dawn for anyone who wakes to see it.