Sacagawea has become a giant figure in American memory and mythology. There are more statues of her than any other woman in America. But we know little about the facts of her actual life.

Driving recently from Salida, Colorado, to Cody, Wyoming, I realized I was within range of the grave of Sacagawea on the Wind River Indian Reservation near Lander, Wyoming. I was in a bit of a hurry, but how many times in a life do you get close to a little visited Lewis and Clark memorial?

I had never been to this Sacagawea grave before, though I had driven the splendid state highway, WYO 789, between Lander and Thermopolis, Wyoming, a dozen or more times. After the usual small difficulties, I found the cemetery west of Fort Washakie. It was about 7 p.m. on a perfect Great Plains day — a soothing breeze, a giant blue sky with high wispy clouds. I had seen photographs of the grave marker before, but I tiptoed through the dry grass of an acre of graves, mostly Native, to a statue of a young, beautiful woman leaning into the future. It had to be her.

A 40-something white couple was studying the signage, holding a video camera. It soon became clear that the woman was intending to record a video for her “podcast.” I said, “You know that she is also buried in another place, don’t you?” “Yeah, we heard something about that,” the man said. I said, “The other site is on the North Dakota-South Dakota border, at the confluence of the Missouri and the Grand Rivers.” They listened politely but I could tell that my commentary was unhelpful, even annoying.

Finally, I said, “Is this the actual grave?” I was pretty sure it wasn’t, but the woman solemnly informed me that this was exactly where she was buried, right under our feet. Saw it on the internet. I took some photographs of the memorial, from every angle, including the signage, and sat for a few minutes thinking about the rich tangled maze of the Sacagawea story. The fact is we don’t know for certain where she is buried. We don’t know for certain where or when she was born. And though we know some of the things she did in the course of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and a few of the things that happened to her along the way, we still don’t know quite how to characterize her contributions to its success. And we still don’t know quite how to define her role, official or unofficial, between November 4, 1804, and August 18, 1806.

Sacagawea Is “A Riddle, Wrapped in a Mystery, Inside an Enigma.”

All that we know about Sacajawea/Sacagawea/Sakakawea/Janey (Lewis and Clark spelled her name over a dozen ways) would not fill a passport book. She gave birth to what Lewis called “a fine boy” at or near Fort Mandan on February 11, 1805. She got very sick near the Great Falls of the Missouri; Lewis thought she might die. She gave William Clark two dozen weasel’s tails for Christmas 1805 at Fort Clatsop, near Astoria, Oregon. She insisted on seeing the beached whale on the Pacific Coast. She showed poise and resourcefulness when her inept husband Charbonneau nearly sank the White Pirogue on May 14, 1805, in eastern Montana. She appears to have done quite a bit of craft work along the trail, some of which she traded for a horse. She had a blue beaded belt that the captains appropriated to purchase “a roab made of 2 Sea Otter Skins” from the Chinooks. She danced for joy when she was reunited with the Shoshone near today’s Salmon, Idaho.

Was she born Shoshone, captured by the Hidatsa, acculturated into Hidatsa traditions, and given a Hidatsa name — Sâh-câ-gar me-âh as Lewis thought he heard it — and married off to Toussaint Charbonneau? Or as the distinguished Hidatsa elder Gerard Baker and other Knife River historians insist, was she Hidatsa (or possibly Crow) all along, captured by the Shoshone, but safely back in the Hidatsa world by the time the Expedition reached the Mandan and Hidatsa villages at the end of October 1804? Did she die young, on December 22, 1812, at Fort Manual Lisa on the Upper Missouri, of what a local official called “putrid fever;” or did she live for many decades after Lewis and Clark left the scene, become a much-respected holy woman, spend time among the Comanche, and die, at the age of 100 or more, on April 9, 1884, on the Wind River Indian Reservation?

Nobody knows for sure. Such inconclusive evidence as we have favors Sacagawea’s early death. That was how William Clark understood it.

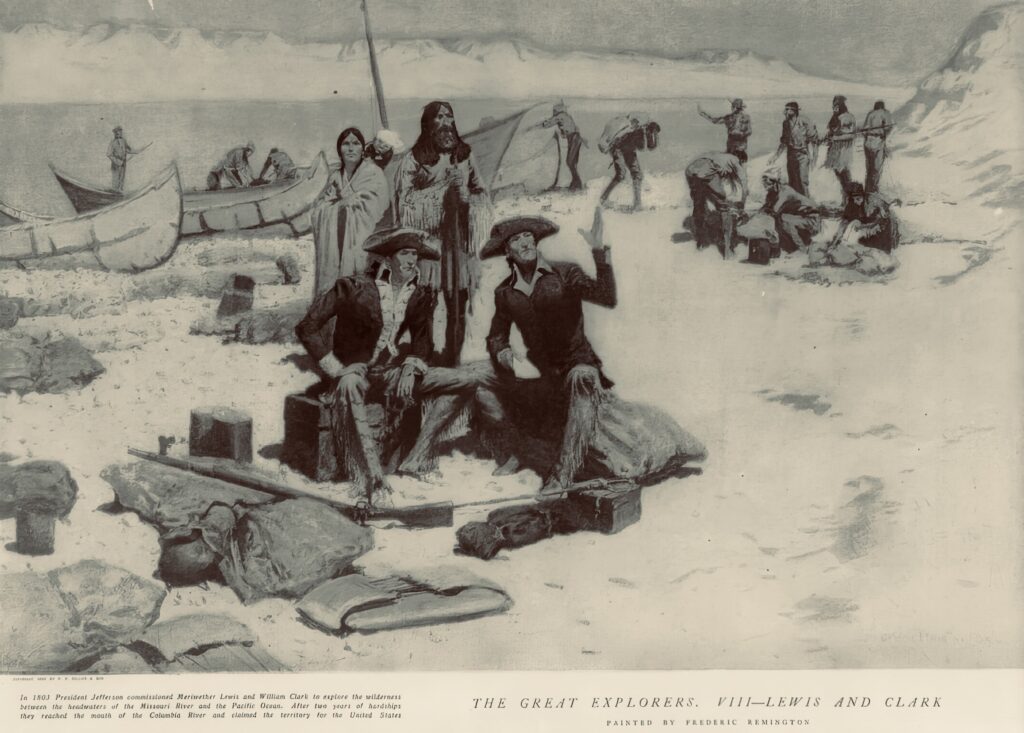

The historians and the interpreters of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial did their best to retire the traditional view that Sacagawea guided Lewis and Clark to the Pacific and back, but they were not successful. The website RoadsideAmerica.com begins, “Indian guide Sacajawea helped lead Lewis and Clark’s expedition to the Pacific Ocean.” In our national memory, the first or second most famous Native woman in American history will always be pointing towards the pass, towards Beaverhead Rock, towards Shoshone Cove, towards the Pacific, or — more accurately — towards Bozeman Pass. However erroneous this idea is, it has extraordinary tenacity, in part because it conforms to our desire to believe a comely and cooperative Native woman showed us the way to create Mr. Jefferson’s “empire for liberty such as the world has never previously seen.”

As I sat at the monument thinking about all of this, it became clear that the woman with the video camera was not going to record her podcast as long as I was within earshot. She seemed to think I would be a podcast killjoy, raising my eyebrow at whatever quirky, postmodern, free-floating, and ahistorical commentary she recorded at the site. I would have liked to have heard it, but since she wanted privacy, I moseyed on down to the actual grave marker (“actual” is a contested term here) to pay my respects.

Whatever she actually was between 1787-1812 (or 1884), Sacagawea has become a giant figure in American memory and mythology. There are more statues of her than of any other woman in America. The modesty of the fact base has not prevented novelists, beginning with Eva Emery Dye and more recently Anna Lee Waldo, from writing heavy tomes about her life. Nature abhors a vacuum. We would give anything to be carried back in a time machine to an average day on the Lewis and Clark trail — to describe how she looked, how she dressed, when or if she smiled, how much she spoke, including how much English she picked up along the way, to observe her with her young son and her old husband.

That would be a cultural revolution. But when that time traveler came back from the trail, even if possessing what Jefferson called “a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves,” would we choose to accept and absorb that testimony, or just continue to load onto her undoubtedly strong back whatever cultural baggage most satisfied us at any given time: guide, suffragette, Native diplomat, embodiment of peaceful intentions, exemplar of domesticity, or — as she has more recently been described — survivor, woman of pluck and resourcefulness, like the cliché about Ginger Rogers, doing all that they did, but in high heels and dancing backward?