A stop at a West Texas Barnes & Noble persuades Clay that books remain alive and kicking.

It’s said that the Age of the Book is ending. There are so many ways to get information and entertainment now that sitting down with an actual book to do sustained reading is regarded as too time-consuming — maybe even tedious. The pace of American life is now so frenetic, and the avalanche of video entertainment is so compelling and addictive that people don’t sit down after dinner to read for a couple of hours — or on a chilly autumn Saturday morning.

True books are not taught much in our K-12 public schools anymore. In most school districts around the country, students still read, but in small bites. They read carefully chosen “stories” that reinforce the values of tolerance, respect, and diversity, but they don’t read full novels anymore. Public school teachers increasingly declare that their pupils are now actually incapable of reading a full book like Lord of the Flies, Fahrenheit 451, To Kill a Mockingbird, or Catcher in the Rye.

If this is true — and apparently it is through vast swaths of America — we are headed into the abyss. True literacy, coupled with critical thinking skills, is essential to any civilization, particularly a democracy where we expect the people to make good choices about their leaders and public policy. A nation without the humanities is in steep decline.

As Hamlet says, “It is not, and it cannot come to good.”

And yet.

This morning, I’m sitting in a Barnes & Noble in a West Texas town of about 190,000. Barnes & Noble stores are dying all over America. When you go in one now, you must search for books through the maze of board games, emoji dolls, Lego and other construction projects, ingenious toys, leathery journals, wry greeting cards, painting kits, and graphic “novels.” There is a café here where I can surf the internet. I’m tired. These have been some very hectic weeks. I want to sit here for five or six hours sipping coffee and browse-read books I collected from “history,” “fiction,” “current events,” and “new releases” before I ventured into the café to get my latte and banana nut muffin.

“Are you a member?” Yes. I save $.34 on the ingestibles.

From 20 minutes of wandering the store, I can attest that reports of the death of the book have been greatly exaggerated. Even in a limited recon, I found dozens of books that I want to read, that I should read, and some that I must read for the kind of work that I do. Just before I walked in, standing in the parking lot, I had a phone conversation with one of my brainiest friends. He recommended a new book, Keeping the Faith, on the Scopes Trial (the “monkey trial”, July 1925) in Dayton, Tennessee. And then he suggested I visit Dayton later this fall on my Steinbeck Travels with Charley national tour. I immediately said yes to both propositions. H.L. Mencken’s essay on the Scopes Trial and the evisceration of William Jennings Bryan is one of the funniest essays in the English language. As my friend said, the issues of the Scopes Trial (science v. fundamentalism, evolution v. evangelicalism, censorship v. freedom of thought) are current all over again in America.

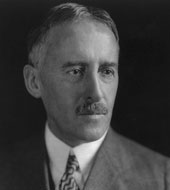

So, I limited myself to just four books to haul into the café, but with real regret that I could not bring in a pile or 10 or more. I’ll only buy two of them, plus a map. One on Henry Stimson (1867-1950), one of my heroes. He was one of the 20th century’s great (and largely unremembered) men. He worked for both Roosevelts (TR & FDR), played a key role in the winning of World War II, and saved the ancient Japanese city of Kyoto from being vaporized by the atomic bomb in 1945. You may have seen a not-very-accurate cameo of Stimson in Christopher Nolan’s excellent film Oppenheimer.

But I wanted to buy two new books on Vietnam, one by my friend Geoffrey Wawro, a professor of history at the University of North Texas in Frisco. He’s one of the most impressive public speakers I have ever met. He has books on World War I, the endless morass of the Middle East, and the Franco-Prussian War. There are half a dozen important new books on the political situation, including Bob Woodward’s War.

B&N has half-acres of self-help and diet books (I may be beyond self-help — or any help — by now) and highly affordable editions of most classics — from Dostoevsky to Vonnegut and everything in between. If I made a list of the greatest books I have never read, I would have to hang myself from shame. If I did nothing but read 10 hours a day for the rest of my life, I could never catch up with the classics alone (Middlemarch, The Remembrance of Things Past), much less the 500,000+ new books published every year in America alone. (By the way, the Arab world publishes approximately 6,500 books per year.) When you listen to “books on tape,” or, as we now say, audiobooks, you can turn up the speed to get more words across the threshold per hour. If I could triple my visual reading speed — believe me, I’ve tried — I could still never read the books that matter greatly to my range of interests in literature, history, religion, philosophy, and science.

In other words, though I am a very serious reader, up to five hours per day, I am falling behind — and, in fact, at an accelerated rate. Alas. It’s daunting. It makes me want to weep sometimes.

Who is writing all of these books? How do they do it? How does Douglas Brinkley publish a new fat book every two years? How has H.W. Brands published more than 30 books, most recently America First: Roosevelt vs. Lindbergh in the Shadow of War? What are they, Isaac Asimov (500 books) or Louis L’Amour (150 or so)?

As I wander the shelves, I see plenty of books that attract my attention, and I briefly think, “I should read that,” but then at least a modicum of good sense steps in. I know I am not going to read a book on how Persia became modern Iran at 857 pages. I know I am not going to read a 700-page book on the history of the Popes. I know I am not going to read a book called The History of the World in Twelve Cups of Coffee or Fred Astaire and the Remaking of Hollywood in the 1940s. Nor do I want a B&N signature book, a coffee table tome on John Deere Tractors, or the Wonders of Florence.

All one can do is plug along, subscribe to all the book review publications, listen to audiobooks on flights and long drives, and — above all — never turn the television on, ever, period!

It’s time to get on the road. The famous lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) said the book publishing industry was “a universal conspiracy for the destruction of trees.” Wait, is that the precise quotation? Excuse me while I venture back into the stacks to see if I can find a book of Dr. Johnson’s witticisms.