Clay will join noted author and MacArthur Fellow Patricia Limerick at the Vail Symposium in Colorado on August 21 to discuss George Orwell’s novel 1984.

I’m preparing to spend an evening with the great Patricia Limerick at the Vail Symposium in Colorado on August 21. If you don’t know Patty’s work, I urge you to read her revolutionary book, Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (1987). She’s a genius, one of the most sought-after public intellectuals in the United States, and almost certainly the most whimsical. She won the MacArthur Prize (the genius award) in 1995. I’ve worked with her a dozen or more times over the years. It’s always an amazing experience to be in the room with Patricia Limerick: think, then, what it is like for me to be me on stage with her, not quite knowing what is about to come out of her brain but sure that it will be extraordinary.

Our subject in Vail is George Orwell’s 1984. I’m somehow to impersonate the novel (1949) or perhaps a modified limited George Orwell himself.

The inevitable question is: are we living in 1984? In the era of “fake news,” the “media is the enemy of the people,” and “alternative facts,” we can certainly feel echoes of Orwell’s famous post-World War II dystopian novel, with its “doublespeak” its thought police, and its memory holes. And yet, even in my least trusting moments I do not believe Big Brother is watching me — if you define Big Brother as a totalitarian government. I do believe, however, that Big Capitalism is watching me. A decent hacker could learn much about my life, habits, utterances, purchases, and movements from his mother’s basement. What I hate about that is that I am complicit in losing privacy. How many times have I permitted some new app, gadget, or website access to my postings? And even when I have not stupidly permitted such intrusions, I am certain that corporate America data mines my life, and everyone else’s, at will. So far not to blackmail us, but only to sell us fast food and mattresses.

Big Brotherism

I don’t know what Ms. Limerick thinks about the big brotherism of our times. She is never ideologically predictable. But as a historian and lover of the truth, surely she is deeply concerned about the deliberate attempt by some partisans to destabilize the representation of truth in American life. We don’t need “alternative facts” to know how many people attended Mr. Trump’s 2017 inauguration. If partisans can convince tens of millions of Americans that January 6, 2021, was just another day of U.S. Capitol tourism and that the thugs that attacked and wounded more than 140 policemen and women were just innocent protesters, we may be doomed.

At least so far, I sense that we have more to fear from AI than from an authoritarian government. In Orwell’s Oceania, printed newspapers, pamphlets, books, and photographs are doctored to suit the government’s latest propaganda needs. Orwell was basing these clunky manipulations on actual Soviet processes, in which a discredited official disappears from a photograph of top party leadership. In 1984, doctored newspapers have to be physically reprinted. So, too, books that have been deemed subversive. In our time, everything can be doctored digitally in ways that will soon be undetectable, including audio and video. We are just now entering a brave new world of uncertainty about the authenticity of … well, everything. Orwell could not have imagined such technologies, but you can imagine what he would have done with them in his imagined dystopia.

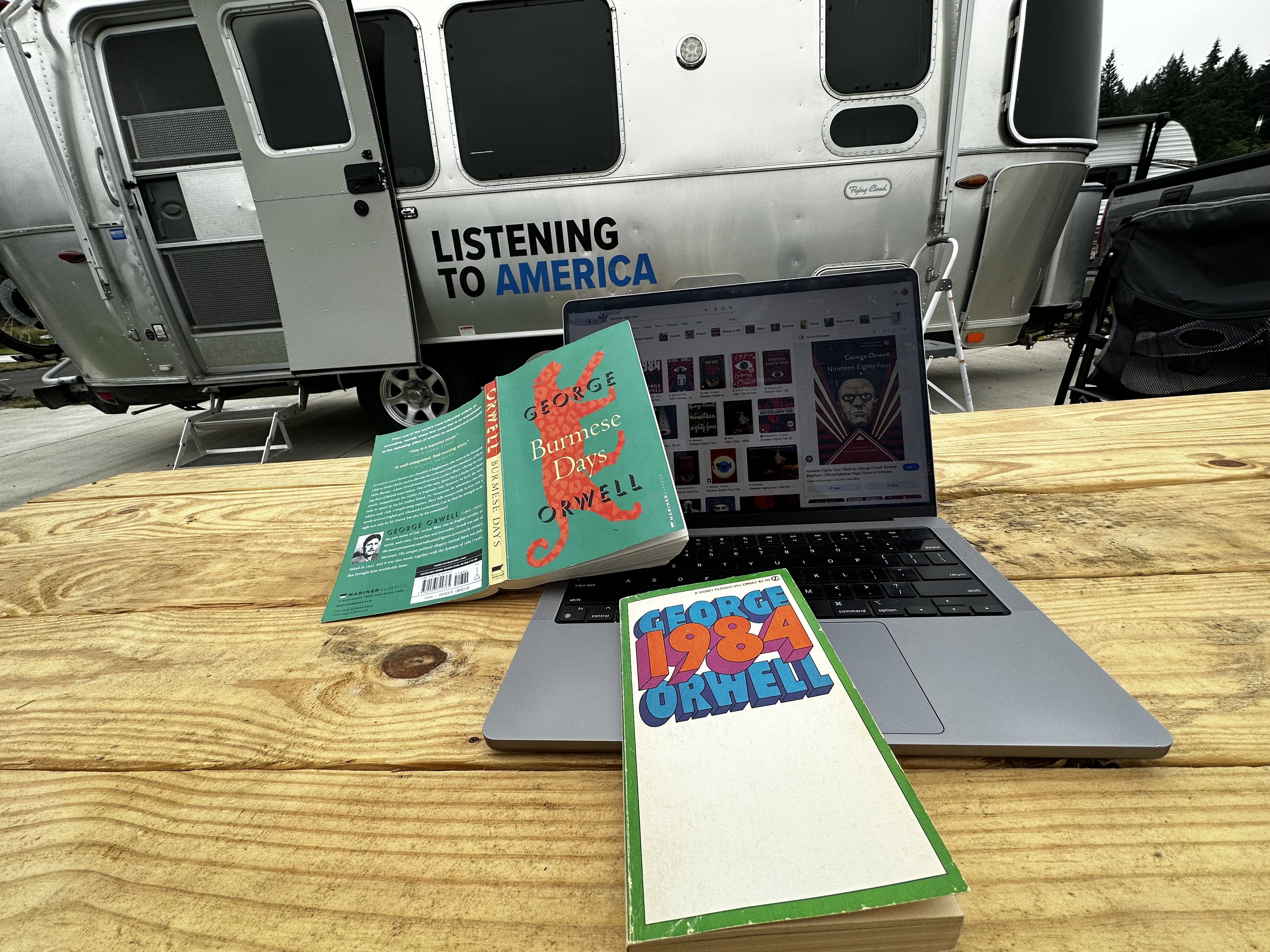

To prepare for this encounter, I have read 1984 a couple of times, taking careful notes, marking up my Signet paperback copy (purchased in 1975), and listening to the book on tape.

Yesterday afternoon, the first day in several weeks I could devote to reading my intended five hours a day, I picked up a copy of Orwell’s first novel, Burmese Days, published in 1934 in the U.S.

Confession time. I’ve admired Orwell all my life. I suppose 1984 was the first of his books I read. Still, when I studied at Oxford University in England, I started to read Orwell’s essays with great joy: among them, Shooting the Elephant, Why I Write, Politics and the English Language, Confessions of a Book Reviewer, Rudyard Kipling, A Hanging, and Dickens. By now, I have probably read 1984 10 or 12 times, but I often turn to Orwell’s marvelous essays when I want to spend an evening in purely joyful reading. I read Christopher Hitchens’ essays if I am in a darker spirit. Hitchens loved Orwell. In many respects I believe he shaped his writing life (and much of his politics) from careful reading of Orwell. Hitchens’ Why Orwell Matters is an excellent introduction to the work of two gifted British curmudgeons: Orwell (1903-1950) and Hitchens (1949-2011).

But here’s the confession. Until yesterday, I’d never read Burmese Days. I’m not sure why, but it has never grabbed me from the pile of other “books that must be read.” Now, because I have to face the whimsical genius in Vail, I’m reading around 1984 in case she throws me one of her famous curve balls across the stage.

Fortunately, 1984 is so great a book because it is a mediocre novel. That may be one reason I had not read Burmese Days and several others before. If the plot of 1984 is the best he can do, why pick up the others, which are books of little historical importance? Even people who have never read 1984 know basically what it is about. The novel occupies the same category as other novels (you don’t have to read to know what they are about), Robinson Crusoe, Don Quixote, and Gulliver’s Travels.

How wrong I was. Almost appallingly wrong. Burmese Days is in some ways a much more important book than 1984 because it is about imperialism. As it existed in the 1930s when the British Empire was on its last legs, but also as colonialism and the systematic exploitation of underdeveloped (formerly “Third World”) nations still exist, some of it initiated or protected by the United States of America. The dystopia of 1984 never happened, not in the West at any rate. About half the world’s countries indeed have some version of Orwellian nightmare governments, characterized by the censoring, bullying, torturing, “disappearing,” and doublespeak central to Orwell’s novel. The Orwellian dystopia has not come to pass in the West, thus making the novel seem a bit silly (or alarmist), a species of science fiction. But Orwell’s severe critique of the British Empire in India and Burma (Myanmar) is the best I have ever read. It’s chilling. It’s sickening. The “Colonel Blimp” figure, agent of the British Raj, unreservedly and grotesquely racist, vapid, lazy, entitled, and smug, is perfectly represented by Orwell, who lived in Myanmar between 1922 and 1927. I feel ashamed that I have not read Burmese Days until now. I urge you to do so. It suffers somewhat from Orwell’s weakness as a novelist; his savage critique of the “white man’s burden” in Asia is much better than the novel’s plot or the working out of the narrative. You have to read Orwell as an essayist trying to be a novelist.

Still Learning to Know America

The last five years have been revolutionary in my life. After the murder of George Floyd (May 25, 2020), I woke up and began to read such books as Carol Anderson’s White Rage, Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, and Beverly Daniel Tatum’s Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?; but also David Truer’s Rez Life, and Philip Deloria’s Indians in Unexpected Places and Playing Indian. I don’t agree with everything in these books, but I believe some or all of them are essential reading for every American with an open mind and a good heart as we approach the 250th birthday of the United States. I thought of myself as a well-read, well-educated man, but when I read these books I was gobsmacked by my shameful ignorance. How do I say this? What I thought I knew about “American history” was considerable. But what I knew about “Black American history” was spotty, wholly ignorant of very important events and even periods, and shallow. In other words, I did NOT know American history because how can you talk about American history with Black people playing only minor and occasional roles? With Native Americans represented only by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse?

How can you know America (I am asking myself) if you haven’t read Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave? If you haven’t read Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God as well as Huckleberry Finn? If you haven’t read Black Elk Speaks or House Made of Dawn?

Here’s the paradox. To wake up to the full(er) history of America is to become sober and perhaps even radicalized. If you let the truth of the Sand Creek Massacre (1864) or the Tulsa Riots (1921) in, or the theft of the Black Hills (1876), or how the interstate highway system bore through the least well-represented neighborhoods in America’s cities, or the way the national parks and monuments were carved out of Native American homelands, you can never look at American history in quite the same way again. Gender matters here, too, of course. Imagine how hard it was to be Sojourner Truth (1851). For that matter, imagine how hard it was to be Betty Friedan (1963)? If I am right, that to wake up is to be drawn away from the comfortable Eurocentric narrative we have been telling ourselves for the last two centuries and into a more nuanced, more untidy, more unsettling, more problematic understanding of the American project, I understand why millions of good Americans want to resist this revisioning of our history. It’s painful. And we have to revise downward our sense that America is the exceptional class act of world civilizations. We are a great people and a great country, but we are also a nation in a world of competing interests, and human nature was not left behind in Europe when our forebears crossed the Atlantic to America. Alas, John Adams was right. When he heard Jefferson talk about the goodness of man, Adams replied (I paraphrase), “Have you looked around, Mr. Jefferson? Have you observed your fellow Americans?” He may also (privately) have wondered what the value of such pronouncements about human goodness meant coming from a man who trafficked in his fellow human beings.

I love America. I love our achievement as a nation. Almost more than anything else, I cherish our national ideals, many of them articulated by Jefferson, some by Lincoln, some by Martin Luther King, some by Eleanor Roosevelt, and some by LBJ. Jefferson may not have been a realist. Maybe he was an “intellectual voluptuary,” as Hamilton called him, a utopian or a dreamer, as others alleged. Still, I know absolutely that I want to live in a republic envisioned by dreamers, even if they did not always live up to their magnificent Enlightenment ideals.

I want to be fully informed and, if possible, enlightened. At the end of that process, I still want to feel mostly positive about the American experiment. I believe I will. But so much now depends on whether we continue to fight for the American ideals of human rights, equality, respect, truth, dignity, opportunity, justice, and fairness in the next decades.

Yet again, I owe Patricia Limerick heartfelt thanks. I’m not sure what will “go down” on that Vail stage in a couple of weeks, but just bracing for it has opened a new appreciation for George Orwell in me. If you have not read Burmese Days, I urge you to do so.