Russ Eagle builds on his previous list of John Steinbeck biographies by looking at works that focus on specific relationships and periods in the author’s life.

In Sea of Cortez, the combination travelogue and philosophical dissertation that John Steinbeck co-authored in 1940 with his good friend Ed Ricketts, the writer scoffed at what he called “the myth of permanent, objective reality.” As observers, he insisted, we bear too many limitations — as individuals and as a species — to know any situation wholly and perfectly. But for Steinbeck, that didn’t mean we shouldn’t try to understand the world. The wider the net one casts, he suggested, the more complete and accurate the picture that emerges. “Peepholes” was a favorite Steinbeck term for perspective, and he believed that by expanding the number of peepholes in one’s repertoire, an objective and more complete truth would grow closer and closer.

We can apply this same idea to Steinbeck’s biographers. Each brought personal limitations and prejudices to their particular project, each went about their research differently, and each provided distinctive nuances and subtleties to their portraits of Steinbeck. In Part I of this series, I discussed what are generally considered the four primary works on Steinbeck’s life and work. The picture that emerges as we read, say, Jackson Benson’s The True Adventures of John Steinbeck: Writer, is only sharpened by a subsequent reading of William Souder’s Mad at the World. Each work is a peephole, and every peephole hones the developing image.

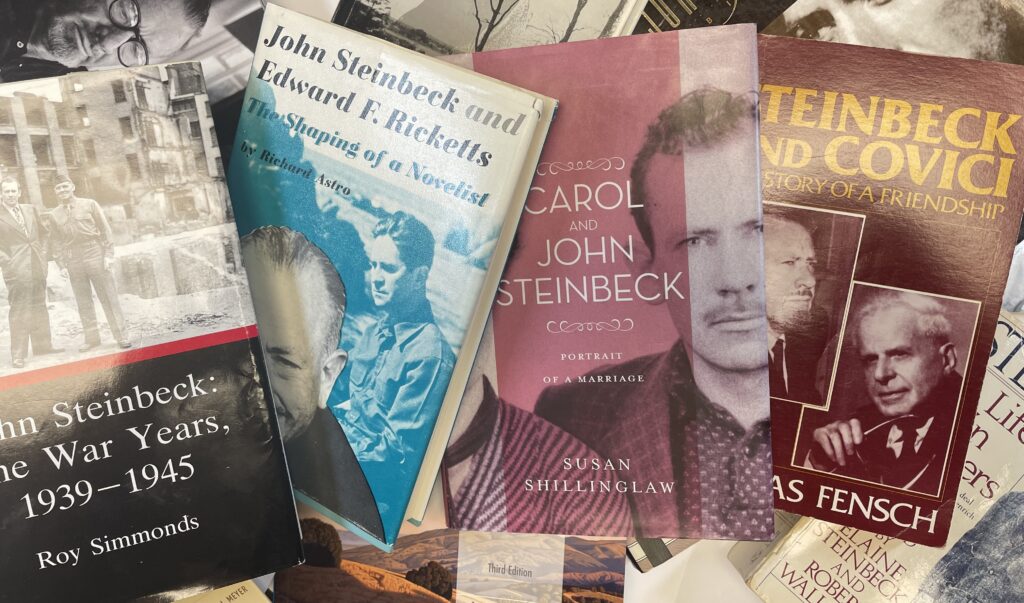

Books of great scope must, however, sacrifice the micro for the macro, the specific for the general. There are more specific works on Steinbeck that focus on close relationships or particular periods in his life. They provide valuable peepholes of their own, with each serving to bring a facet of Steinbeck’s life into clearer focus. Four of the best of these works are described below. They include book-length studies of three of Steinbeck’s most important relationships: his first wife Carol Henning Steinbeck; his longtime editor Pascal Covici; and his legendary friend Ed Ricketts. The fourth is a detailed description of Steinbeck’s experiences during one of the most interesting and tumultuous times of his life — the years of World War II.

Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage

Susan Shillinglaw (University of Nevada Press, 2013)

Though most know Ricketts as Steinbeck’s great friend and inspiration — he was the real-life Doc of Cannery Row, among other things — I would argue that no relationship in Steinbeck’s life was more important to his work than his first marriage. Like Benson, Shillinglaw spent years researching and writing this book. It focuses on the years — the 1930s — and the relationships — not only Carol but Ricketts and a host of others — that saw Steinbeck grow from an unknown to one of the handful of best-known writers in the world. Shillinglaw portrays Carol as a defining presence in Steinbeck’s life during this period, throwing her own considerable intellect and energy into her husband’s work. She chronicles the couple as working together as a team, particularly during the period that produced The Grapes of Wrath, something that Steinbeck acknowledged in that book’s dedication: “To Carol, who willed it …”

John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a Novelist

Richard Astro (University of Minnesota Press, 1973)

Published in 1973, just five years after Steinbeck’s death, this is the volume that established the now common perception of Ed Ricketts as a major influence on Steinbeck’s work. The period that Steinbeck and Ricketts were in each other’s daily company was relatively brief and sporadic, but the intensity of their relationship and the ideas and interests that they shared certainly had a monumental effect on the author’s work. Ed Ricketts was a fascinating individual in his own right, and Astro shares his story as well as the synergy that developed between the two men during the most fertile period of Steinbeck’s career. Debates on Ricketts’s impact are de rigueur at any gathering of Steinbeck enthusiasts, and Astro’s volume is the starting place for anyone wanting to join the discussion.

Steinbeck and Covici: The Story of a Friendship

Thomas Fensch (Middlebury, 1979)

Pascal “Pat” Covici was Steinbeck’s editor and publisher for 30 years, beginning in 1934 with Tortilla Flat, the author’s first major success. Once Steinbeck moved to New York in the 1940s, Covici also became a close friend. When Steinbeck wrote East of Eden in 1950, he began each writing session with a note to Covici, letters that were published in 1969 as Journal of a Novel. Fensch extracted this chronicle of friendship primarily from the extensive written correspondence between the two men. He effectively portrays Covici’s essential and multi-faceted role in Steinbeck’s life as protector, friend, and cheerleader. Covici ordered paper and pencils for Steinbeck, tracked down books and personal items for him, and performed many other duties not ordinarily associated with the responsibilities of an editor. Covici was, according to Steinbeck, “my collaborator and my conscience.”

Pat Covici was much more than my friend. He was my editor. Only a writer can understand how a great editor is a father, mother, teacher, personal devil and personal god. For thirty years Pat was my collaborator and my conscience. He demanded of me more than I had and thereby caused me to be more than I should have been without him.

John Steinbeck, eulogizing Pat Covici in 1964.

Steinbeck: The War Years, 1939-1945

Roy Simmonds (Bucknell University Press, 1996)

Steinbeck’s life was never so turbulent as during the years covered here. The Grapes of Wrath was published, the resulting fame, wealth, and controversy drove the author into depression and destroyed his marriage, and the world went to war. Anxious to serve his country and yet blackballed from military service, Steinbeck took to writing war propaganda. He jumped quickly back into marriage with a woman 15 years his junior, then immediately headed overseas as a newspaper correspondent. Five months later he limped home, physically and psychically damaged, almost certainly suffering from PTSD. Cannery Row, which Simmonds labels here as “a new masterpiece,” was published shortly thereafter, and for many scholars came to represent the end of Steinbeck’s years of greatness. Simmonds, an independent British scholar, set out in this study to determine and detail the causes of Steinbeck’s “astonishing and disastrous fall from critical grace” in the postwar period. He provides the most exhaustive look available at Steinbeck’s wartime output, as well as at the personal and professional goings-on in this pivotal chapter of Steinbeck’s life and reputation.

Though the last three books described above are out of print, they can be easily found on used book sites.