John Marshall’s service with George Washington at Valley Forge helped shape his very different view of America’s new republic than that of Thomas Jefferson.

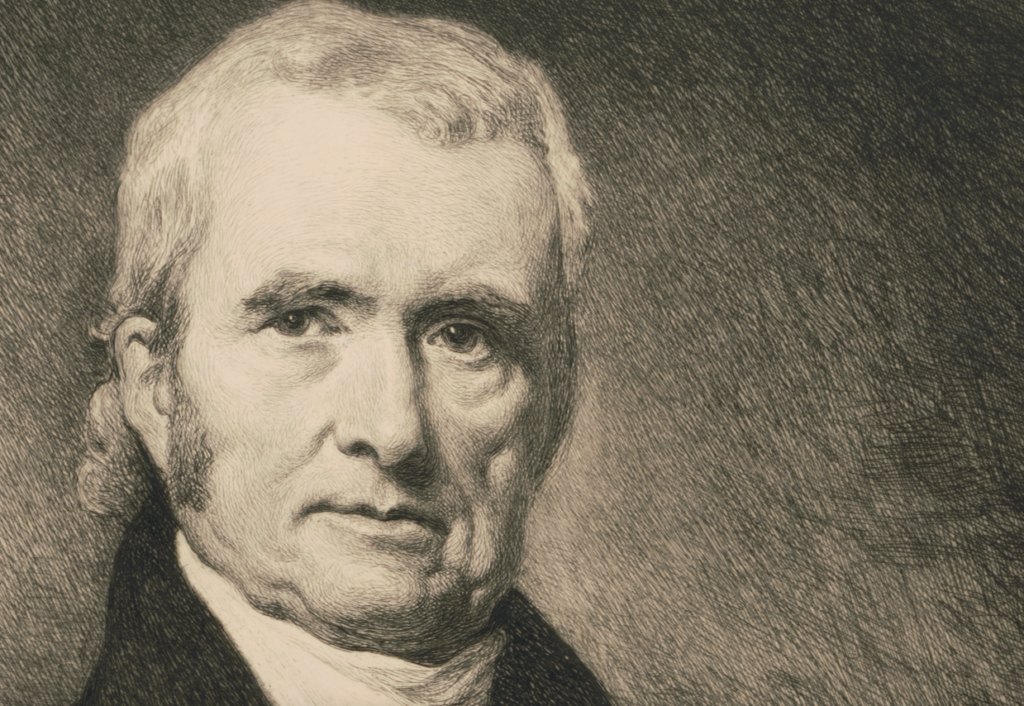

John Marshall served as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and was a longtime rival of Thomas Jefferson. (Library of Congress)

Thomas Jefferson’s rivalries with Alexander Hamilton and John Adams stand among American history’s most studied examples of partisan politics. Jefferson’s contrasting views with these two high Federalists sparked a great deal of bitterness and still fuel debate after more than two centuries. But while Hamilton and Adams emerged from different worlds, a third Jefferson antagonist was not only a fellow Virginian but a blood relative of the third president. John Marshall was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by John Adams in the final months of his administration. During his 35-year tenure on the high court, Marshall was involved in decisions that clashed with Jefferson’s beliefs, including many that confirmed the federal government’s supremacy over the states. That judicial record, however, wasn’t the only source of the friction between Marshall and Jefferson. Clay and Lindsay Chervinsky sat down to discuss why these two Virginia cousins never seemed to agree. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

Clay Jenkinson: John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson were third cousins once removed. They were both Virginians and plantation owners, and both had fathers who were surveyors. And yet these two men did not like each other. Jefferson said of Marshall that he was a man with “lax lounging manners.” Marshall not only goes to taverns, complained Jefferson, but he had been seen playing billiards.

Lindsay Chervinsky: This reveals so much about both of their characters. Marshall was friends with everyone, including Madison, Gallatin, and John Randolph; these were much more radical Republicans than Jefferson. Marshall was also friends with the highest of High Federalists, who criticized him and Adams for their moderate stances. And yet he hated Jefferson, and the feeling was mutual. It’s my sense that Jefferson resented how easily Marshall got along with everyone. Marshall was easygoing and genial and good with the jokes. He was so effective at socializing that people called him Mr. Barbecue. Jefferson, despite his brilliance, was uncomfortable in larger groups, and he probably resented Marshall’s ease with crowds.

Clay Jenkinson: Jefferson was shy and aloof. He was a little socially awkward, especially on first meeting. He didn’t like crowds. He didn’t attend balls. He preferred to be at his fortress of solitude in Virginia. He didn’t have any of those loose lounging tavern capacities. The eminent American historian Jean Edward Smith said of the two men: “An exemplary aristocrat who advocated democracy, Jefferson was never comfortable associating with the common man. Marshall, who distrusted democracy, never lost the common touch. Jefferson opposed an energetic central government as a danger to individual liberty. Marshall saw the government in Washington as the keystone of national well-being. Jefferson identified with Virginia and Marshall with the United States. Jefferson favored agriculture and advocated the virtues of rural life. Marshall, an avid farmer himself, was more attuned to the needs of commerce and industry. In some respects, the differences involved the classic tension between the man of ideas and the man of affairs. Jefferson was at his best when articulating a philosophy of government, Marshall when applying one.”

Lindsay Chervinsky: A perfect description.

The Constitution vs. Articles of Confederation

Clay Jenkinson: They were two titans, Marshall over at the Supreme Court and Jefferson, the third president of the United States. Marshall’s decisions between 1801 and 1835 pushed the country into a more centralized national constitutional order. You could even say that he in some sense distorted the Constitution to make it still more powerful than it was, whereas Jefferson was always uneasy about the Constitution and preferred the Articles of Confederation. That has to be one source of trouble.

Lindsay Chervinsky: It’s certainly ideological. They had very different views of the world, the nation, and what the government should be. They had different views of mankind and took different approaches to life. And sometimes, people aren’t a good match, and there are times when someone rubs you the wrong way. Some of it was situational. They were both in Virginia, so they couldn’t get away from each other. Each had to constantly grapple with the other’s existence. They were oil and water.

Clay Jenkinson: I think Jefferson believed that all Virginians should be like him. That is, if you’re from Virginia, you’re from the most important, most populated, and richest state. It bothered him deeply that there could be an extraordinarily talented Virginian like John Marshall who belonged to the enemy, to the Federalist Party, the party of New England, and the Northern states. To Jefferson, Marshall had betrayed his birthright and destiny by not being a good Virginian.

Clay Jenkinson: There were two bands of brothers. One was the Adams and Jefferson band of statesmen, the legislators, the people at the Second Continental Congress, who helped formulate the ideas that became America. And then there was the band of brothers who fought the war. If you didn’t fight the war, as was the case with Jefferson and Adams, it didn’t mean that people didn’t respect you, but there was something that others had that you didn’t have. There was a subtle demarcation between these two camps. Jefferson was not only not a warrior and didn’t serve, but he was widely regarded as a weak wartime governor in Virginia. This gave the people that didn’t like or trust Jefferson another reason for thinking he was not one of them. He couldn’t appreciate the need for a strong national government because he wasn’t there trying to hold a ragtag army together with the protocols of the Articles of Confederation. He doesn’t know how difficult it was for Washington to hold an army together through those years.

Lindsay Chervinsky: It’s not to say that those who served in the more diplomatic corps didn’t suffer. They did. They sacrificed, and they were often away from home, and travel across the Atlantic was no picnic. So there was sometimes resentment among that band that their sacrifice wasn’t appreciated in the same way.

Clay Jenkinson: Marshall was part of that diplomatic core as well. He was one of the three American diplomats in the famous XYZ Affair, along with Elbridge Gerry and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. The US was sort of involved in an undeclared naval war with France, and Adams sent this trio over to try to work out this and other disputes. That’s when Marshall became a national figure when everyone realized that he was a man of great substance.

Lindsay Chervinsky: Absolutely. On his return, he was welcomed and celebrated across the nation. It was a defining point for Marshall and the Adams administration, and it had a splintering effect on the Republican party and the Federalist Party.

Jefferson to Marshall: Don’t Be Late for My Inaugural

Clay Jenkinson: One of my favorite stories is about Jefferson’s first inauguration. Marshall had to administer the oath to his enemy, and Jefferson had to take the oath from his enemy. Marshall was famous for not being prompt, so Jefferson wrote him the day before to remind him to be there promptly at noon. And Marshall had written to others that Jefferson was wholly unfit and couldn’t think of anything worse that could happen to the country than to have as its president this Jacobin, this radical, this small-d Democrat. Then, after he administered the oath, Marshall said that he found Jefferson’s inaugural address pretty good and conciliatory. Marshall admitted that he tended to put Republicans into one of two camps – theoretical visionaries or absolute terrorists – and he didn’t think Jefferson was a terrorist. How great that moment must have been with these two colossal figures having to go through this ceremony together. And both behaved properly. That’s what I love about the early national period.

Lindsay Chervinsky: They did. And let me add one additional element. Jefferson needed Marshall’s assistance through the transition. He was taking over at a moment when international relations were complex. Marshall wrote him a report and sent one of his clerks to help Jefferson as his private secretary. And then Jefferson asked Marshall to stay on as Secretary of State until Madison could get into town, which he did. So not only did they behave properly in public when everyone’s eyes were watching, but they also behaved privately behind the scenes and did what was right for the nation to ensure the peaceful transfer of power. And that was essential.

If you would like to hear to the entire episode you can find it here: #1536 Ten Things: Jefferson and John Marshall.