The fishing boat that took the author and his friend Ed Ricketts on their famous expedition to the Gulf of California in 1940 was pulled literally from the ocean floor for an eight-year, $7 million makeover. Recently, it returned to Monterey Harbor, ready to return to work. Listening to America’s special Steinbeck correspondent, Russ Eagle, was there to cover the event.

I first set foot onto the deck of the Western Flyer back in the fall of 2018. The 1930s-era purse seiner had just been moved into the Port Townsend Shipwrights Co-Op after five years in dry-dock. It was little more than a hulking mass of rotten wood, and it had been saved from the landfill only by its 80-year-old connection with John Steinbeck. The ensuing restoration project, which eventually cost $7 million and captured international awards and significant media coverage, captivated Steinbeck devotees and traditional wooden boat construction fans. I remained an active supporter throughout — two pieces of the vessel’s original decking now sit on a shelf in my basement — so when the announcement came a few months back that the Flyer was sea-worthy and returning to Monterey after 75 years, I knew I wanted to be there.

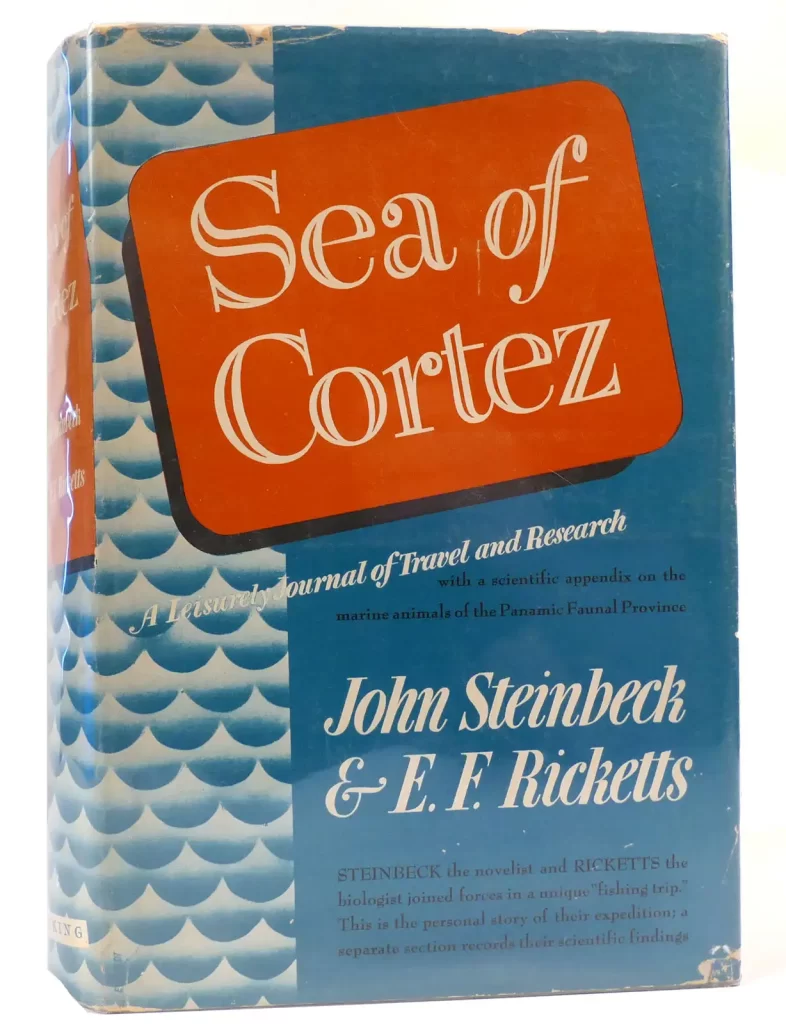

With its storied fishing history, Monterey has served as home port to hundreds of vessels over the last century. None, however, forged a connection with the city in the same way as the Western Flyer, built in 1937 specifically to fish for the Pacific sardine in and around Monterey Bay. That’s mostly because of Steinbeck and his friendship with Ed Ricketts, the owner and operator of Pacific Biological Laboratories on Cannery Row. Steinbeck hired the Western Flyer in the spring of 1940 and he and Ricketts made a six-week expedition to the Gulf of California. Their trip is recounted in Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research. It was the only book on which Steinbeck ever shared authorship, and though it sold poorly at first, it gradually grew into a sort of underground classic of ecological thinking.

The Western Flyer’s tenure in Monterey was brief. The purse seiners became victims of their own success. By the mid-40s, they had caught all the fish, and before the decade was out, the Flyer had sailed out of town for good. By then, Ricketts was dead, Steinbeck was a New Yorker, and Cannery Row was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Though the Flyer would fish the Pacific Northwest and Alaska waters for another half century, there was no longer any reason to return to Monterey. The boat was modified several times and renamed Gemini. In 1971, it hit a reef off the Alaska coast and was nearly lost. It would later sink — twice — and in 2012, it was left sitting at the bottom of Swinomish Slough in northern Washington for six months. Any suggestion at that point that the Western Flyer would ever sail again would have been met with disbelief. But in 2015, a marine geologist named John Gregg bought the boat for $1 million. Sea of Cortez had inspired him as a boy, and he saw something worth saving. Gregg is a humble man who is visibly uncomfortable in the hero’s role, but that is precisely what he became in the Steinbeck world. He wasn’t sure exactly what his plans were, but he pledged early in his efforts to return the Western Flyer to Monterey.

It took him eight years, but John Gregg made good on his pledge. At around 11:40 am on Saturday, November 4, 2023, Captain Paul Tate eased the Western Flyer around the breakwater and back into Monterey Harbor. Hundreds of people lined Old Fisherman’s Wharf, and hundreds more watched from the neighboring commercial wharf, the Coast Guard Pier just to the south, and the parks and trails that line the harbor’s rocky shore. The inner harbor was swarming with kayakers looking to infiltrate the parade of boats that escorted the Western Flyer into the port. People stood in line for hours for the opportunity to step on board. There was a mariachi band. The politicians spoke as they must, but on this day, their speeches struck perfect tones. This was a community celebration, a homecoming, an homage to the fishing families and the industry integral to Monterey’s history. Even the inland town of Salinas, Steinbeck’s birthplace, and Monterey’s longstanding rival as “Steinbeck’s town,” sent a county supervisor with a warm message. Steinbeck, once vilified in his home county and gone now for more than half a century, still draws a crowd on California’s Central Coast.

Steinbeck and Ricketts in the Gulf of California

Steinbeck went to the Gulf of California in 1940 as an escape. He was fleeing the madness that followed publishing The Grapes of Wrath, searching for some vestige of the anonymity he felt was crucial to his work. His marriage was crumbling. The world was descending quickly into war. And, perhaps most importantly, he went because of his friendship with Ed Ricketts. Their ostensible motivation for the trip was to collect marine specimens and study the ecology of the Gulf, but Sea of Cortez is remembered today not so much for its marine biology as for its philosophical ruminations: objective reality, atavism, non-teleological thinking, ecological holism, and the interactive dance between microcosm and macrocosm that permeates so much of Steinbeck’s work. The account is infused with humor and Steinbeck’s remarkable talent for describing the natural world. Like all his great works, it captures the magic of the marginal times of day after the work is done. Steinbeck and Ricketts used these opportunities to play a game they called speculative metaphysics, “lopping off a piece of observed reality and letting it move up through the speculative process like a tree growing tall and bushy.” The beer-stoked sessions that played out on the deck of the Western Flyer led to some of the most quoted passages in all of Steinbeck’s work. Sea of Cortez reads like poetry at times and like an alcohol-fueled bullshit session at others. The ability to walk such a line was central to Steinbeck’s work and success. It’s a big reason his books are still in print. And it’s a big reason why the restoration and return of the Western Flyer means so much to so many.

Travels with Charley remains Steinbeck’s best-loved travelogue. It’s a very American book. It is Steinbeck, that most American of writers, at his most personal. It’s Route 66 in a GMC pickup truck with a camper top and a dog. It’s roadside America, national parks, mobile homes, and 60s-era politics, and the Civil Rights Movement. Perhaps only Kerouac can claim a firmer hold on the American image of a road trip. But the Sea of Cortez journey, taken 20 years earlier, is a West Coast book, a book of the sea. It’s Monterey’s book. It has become a bible of sorts for hardcore Steinbeck enthusiasts. It represents the zenith of the Steinbeck/Ricketts friendship that dominates many discussions of Steinbeck’s work. Travels with Charley may be America’s Steinbeck book, but in and around Monterey and among hardcore Steinbeck enthusiasts all over, Sea of Cortez is the account they keep returning to.

Rocinante, the truck in which Steinbeck and Charley circumnavigated the United States in 1960, now sits in the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas. It is the Center’s star attraction, rightly so, and yet one cannot help but be disappointed in the way the vehicle is displayed. It sits tucked into a corner, visible only as one exits the museum, almost like an afterthought. The surrounding plexiglass frustrates both viewers and photographers. The Western Flyer can anticipate a more productive future thanks to John Gregg and his team. As Gregg said in his short talk that closed Saturday’s festivities, “I don’t think we have accomplished anything yet.” The Flyer will not be moored in Monterey as some relic of the past. A state-of-the-art science lab is going in its old fish hold. The boat, he says, is ready to return to work. Its mission is no longer that of a predator, pulling fish out of the ocean by the ton, by the thousands of tons. In its new life the Western Flyer takes its place alongside the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, San Jose State’s Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, and Stanford University’s Hopkins Research Center, area organizations working better to understand the ocean and our relationship to it. The Western Flyer, Gregg concluded, “can inspire future generations to make better use of the planet than we have.”

It seems trite to ask what Steinbeck would think of the “hooptedoodle” being raised over the renaissance of the Western Flyer. He had a lifelong disdain for publicity of any kind, and he once opined that if his hometown wanted to honor him, the best way to do so might be to name a bowling alley or dog track after him or perhaps a medium-priced brothel. But it’s hard to imagine Steinbeck being cynical this time. The Western Flyer Foundation’s stated mission, “to stir curiosity by connecting art and science,” serves as an apt description of the 1940 expedition as well. The key to the Steinbeck/Ricketts relationship, many say, was that Steinbeck was a writer who viewed life through a biological lens, while Ricketts was a biologist who approached the world through the humanities. Blending art and science was at the heart of their friendship and work together.

After Saturday’s festivities, we left Old Fisherman’s Wharf and strolled down Cannery Row. Ed Ricketts lab, the birthplace of the game of speculative metaphysics, still stands at the far end, dwarfed by the neighboring Monterey Bay Aquarium. The doors to the lab were open, so we climbed the aging steps and went inside. A first edition of Sea of Cortez lay on a table in the front room, fittingly opened to Chapter 2:

“… to nearly all men, a boat more than any other tool he uses is a little representation of an archetype. There is an ‘idea’ boat that is an emotion, and because the emotion is so strong it is probable that no other tool is made with so much honesty as a boat … Apparently the builder of a boat acts under a compulsion greater than himself. Ribs are strong by definition and feeling. Keels are sound, planking truly chosen and set. A man builds the best of himself into a boat — builds many of the unconscious memories of his ancestors … This is not mysticism, but identification; man, building this greatest and most personal of all tools, has in turn received a boat-shaped mind, and the boat, a man-shaped soul. His spirit and the tendrils of his feeling are so deep in a boat that the identification is complete.”