Bismarck, N.D. — Normally I don’t observe the birthdays of my literary and historical heroes. I know Jefferson’s birthday (April 13, 1743) and Shakespeare’s (April 23, 1564), and Bertrand Russell’s (May 18, 1872), and Samuel Johnson’s (September 18, 1709), and not many more, at least by day of month.

Today is John Steinbeck’s birthday. I had never really thought about this before. That makes him a Pisces, if that counts in any way. My sister was a Pisces and one of my girlfriends. Both depended on the kindness of strangers and were in some important respects helpless alone. If this is not just gibberish.

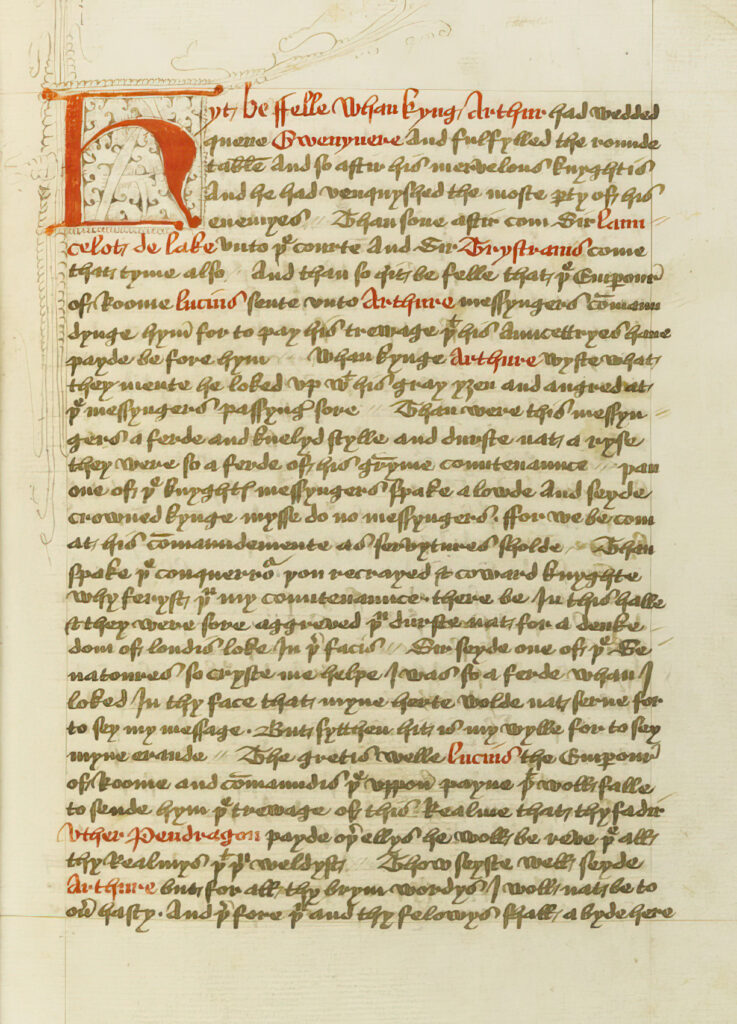

I’m observing this day by reading about Steinbeck and the Morte d’Arthur, the 15th century prose romance about the Arthurian world. Steinbeck attempted to translate the Morte into a slightly archaized modern English. He failed. He claimed that his failure brought on a stroke in the winter of 1959.

I have a very close friend who loves Steinbeck but has trouble with the Morte. I want to help him get over the hump with this book, because once you find the key that unlocks its genius, you never feel quite the same way about any other piece of literature again. I first read the Morte in the late 1970s, in Wiltshire, England, not far from Salisbury. I was spending the summer as a paying guest of a middle class Wiltshire family that needed the extra cash. That summer I spent five hours a day struggling to learn to read Homer in the original Greek. They cleared out a 17th century stable for me and we fashioned a desk. There I sat with the West’s first great poem and a word list and a cheater’s translation (Richmond Lattimore). Later in the day, after a good walk, I read Malory. It took maybe three weeks. I’m sure I took extensive notes, but I have no idea where they are, if they still exist.

Today, almost fifty years later (arghhh) I am reading a book called An Introduction to Malory by Terence McCarthy. McCarthy teaches foreign literature at Dijon, France. I looked that up just now. I would have expected him to be either at a South Carolina university or in a red brick English university like Manchester or Reading. But no. Dijon. I should have guessed by the single “r” in Terence.

McCarthy is talking about how difficult first reading of the Morte can be. Which is precisely my friend’s challenge. And then he says this: “Let us say that for twentieth century readers it is easier to read the Morte Darthur [he spells it thus] for the first time if we have already read it once.” Page 2.

Exactly! I had to stand up when I read this, because it resonates with a koan that I often offer those who sign up for my humanities retreats, my Smithsonian talks, or my online courses. I say, you have to read a great book for the first time, and struggle with it, before you are really ready to read it. The first time we read The Epic of Gilgamesh, or the Iliad, or Dante’s Divine Comedy, or even Moby Dick, we are just trying not to drown. I feel serious sympathy for the college freshman suddenly in a great works course trying to read the Iliad or The Wife of Bath’s Tale for the first time. There are so many obscurities — gods and goddesses, names of major and lesser heroes, battle implements we have never encountered before, literary conventions, tropes, allusions and references, and syntax that is not our own — that many students just drown. This turns them off of great literature — “it’s just too hard,” or “it doesn’t speak to me,” or “I can’t get into it” — and they usually never return. And their professors don’t do them much service, either. In my experience, professors usually wind up just browbeating their students and wringing their hands about the decline of cultural literacy and capacity.

I repeat: “Let us say that for twentieth century readers it is easier to read the Morte Darthur for the first time if we have already read it once.” My way of saying that is that I ache to read Hamlet again for the first time, and I long to read Huckleberry Finn again for the first time.

But we cannot. In reading Crime and Punishment again recently, for the fifth time, I understood the novel so much better than on my first couple of encounters, but I felt the deep sadness of recognizing that something had been lost even as I understood more. The first time you read of Raskolnikov and Sonia alone in the dark room lit by the dying candle, sitting across from each other at a small deal table, the murderer and the harlot, you are overwhelmed with the magnificence of the scene, the mastery of Dostoevsky. That’s just how I felt the first time I read of Miss Havisham’s sallow bridal room in Great Expectations. And the first time I heard Lear say, “Thou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is nothing but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art.”

I can read those scenes a hundred times, even at full attention, but they never again deliver what they did the first time I encountered them. Realizing this produces one of the sharpest pains of my life. I sometimes say that I wish we had that gadget from the Men in Black movies, which blanks out the consciousness of the person who is zapped. But then, of course, reading Hamlet for the first time would be like reading it THE first time, with all the bewilderment and insecurity we felt when we were eighteen.

I’m going to order a copy of this book and send it to my friend the Steinbeckian, in the hopes that a: he has time to give it some attention, and b: that it alters the trajectory of his reading life. I believe it will. That would be the greatest gift of friendship I could ever offer him. You cannot tell when you do something like this if it will work. He may be too busy, may set it aside for next week and never come to it. We have all done that in the face of the encouragements of even our closest friends. But I reckon he will rise to the occasion. I must send the book to him by U.S. Postal Service. To have it sent by Amazon.com is not the same. It will automatically mean more to him when he sees that I chose to take more trouble with the gift.