As the editor of the Lewis and Clark quarterly journal, We Proceeded On, I attended the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation annual meeting in Missoula at the end of June. About 200 lovers of Lewis and Clark gathered at the Holiday Inn downtown for four days of lectures, performances (including by Lewis’ fetching mother Lucy Marks!), round table discussions, one of which I led, awards ceremonies, walking tours, and bus tours to LC-related landscapes within school bus distance of Missoula.

If you are interested in Lewis and Clark, I invite you to become members of the Trail Heritage Foundation, which gets you a subscription to We Proceeded On (WPO).

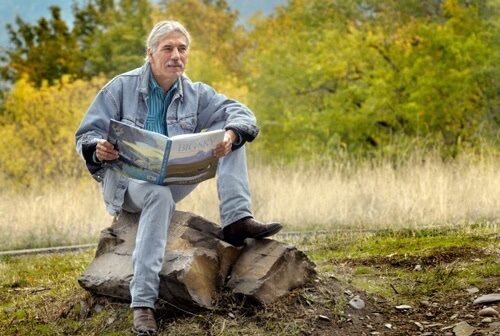

The keynote address was given by one of my favorite writers, Dan Flores. He’s the author of several outstanding books, most recently Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals and People in America. My favorite of his books is The Natural West: Environmental History in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. But American Serengeti is also a must read.

Flores is a warm and gentle man. He has a ponytail and a slightly grizzled look — just enough to remind you these books aren’t written in a library tower.

His talk began with a sobering account of the ways in which Industrial Man has denuded the planet, forced a large number of animals into extinction, with more to come. Just the day he spoke I read about the seals and dolphins dying off the coast of southern California — victims of toxic algae thanks to global warming. It seems that every month we learn of a new way in which human-caused-or-accelerated climate change is wreaking havoc on the biosphere — giant forest fires, savage tornadic waves, atmospheric rivers. …

Because he was in front of Lewis and Clark obsessives, he told the story of the expedition’s encounters with the grizzly bear, which Lewis for a time thought he might name the “variegated bear.” I can hear it on CBS: “There was another variegated bear attack on a tourist at Yellowstone today. …” Lewis famously discounted the ferocity of the grizzly bear, confident in the lethal firepower of 1805 rifles and muskets. But after a couple of harrowing bear fights, during which several of his expedition members (once including himself) might well have been mauled or killed, Lewis said, “I find that the curiosity of our party is pretty well satisfied with respect to this animal. He has staggered the resolution of several of them.” At the Great Falls of the Missouri, on June 14, 1805, Lewis had a harrowing encounter with a variegated bear which propelled him into the river holding his spear (espontoon) in a defensive position. The bear menaced Lewis but declined water combat.

When Flores recounted grizzly bear stories, the banquet audience laughed happily. He was talking to us about us!

His point was not lost in the nods and chuckling. Lewis and Clark encountered their first grizzly bear on October 20, 1804, just south of today’s Bismarck, N.D. Grizzly bears were a plains creature not particularly a denizen of the mountains. Industrial Man forced them up into the recesses of the mountains, along with a range of other species that once flourished in the American Serengeti. Flores estimated that there were once 58,000 grizzlies in the lower 48 states. Lewis and Clark did not run into many grizzlies (minding their own business) until they reached today’s eastern Montana.

When I take cultural tour groups on my annual canoe trip in the White Cliffs section of the Missouri River southeast of Fort Benton, Mont., we are so far from “civilization” that cell phones don’t work and there is no way out until the mouth of the Judith River. Off the grid. Imagine the great river s-curving its majestic way towards North Dakota, a breathtaking blue. And then copses of cottonwoods dotting the river on either bank. Some deer, more eagles and hawks. Few signs of white settlement — some barbed wire fencing, a broken-down log cabin here and there. At some point on the second day, someone says, “It looks unchanged since 1805.” Well, yes and no. Mostly no. No Costco, no asphalt bike path, no wind turbines. But …

The grasses are at least half imports from Eurasia. No bison. No elk. No wolves. No grizzly bears. No Native Americans.

Dan Flores reminded us of how massively and ruthlessly Industrial Man has erased one West and substituted another; and even the places like the White Cliffs where you can still get a whiff of what it once was, those places have been saved from industrial ravagement by concerted efforts of small numbers of American people who want to save something for seed, something for the soul, something that we can agree to leave alone. Thoreau, remember, says “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone.”

Flores knows whereof he speaks. He and his wife Sara Dant (an excellent historian with a new book called Losing Eden) served as advisers to Ken Burns’ forthcoming documentary on the Buffalo (October 2023). He’s prominent in the film. I’m in there somewhere, too, but I don’t know how much or how many banalities I uttered!

At the end of his talk, Flores spoke movingly about the passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 — during the Nixon administration. A full 46 species, including the Humpback Whale, the Grizzly Bear, the Condor, and Bald Eagles have been a least modestly “restored” under the terms of the Endangered Species Act, and more than 200 species have been saved from extinction. There are periods in history when humans come together to do the right thing. That was one of them.

Wilderness Act

Emissions Standards

National Environmental Policy Act

Clean Air Act

Clean Water Act

Endangered Species Act

1964

1965

1970

1970

1972

1973

Not to mention the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities (1965).

It was a lovely talk by an amazing man and a fine writer. There was an implied cautionary note: don’t be so devoted to your great journey story of the past that you forget the conservation imperatives of the present and future. What you love about your story is endangered. Focus some of your zeal on making sure the West is available to your great grandchildren.

My hope is to spend a couple of days wandering the Sangre de Cristo Mountains (or some others) with Flores in the next year. There is so much to talk about, and what better companion/guide than Flores?