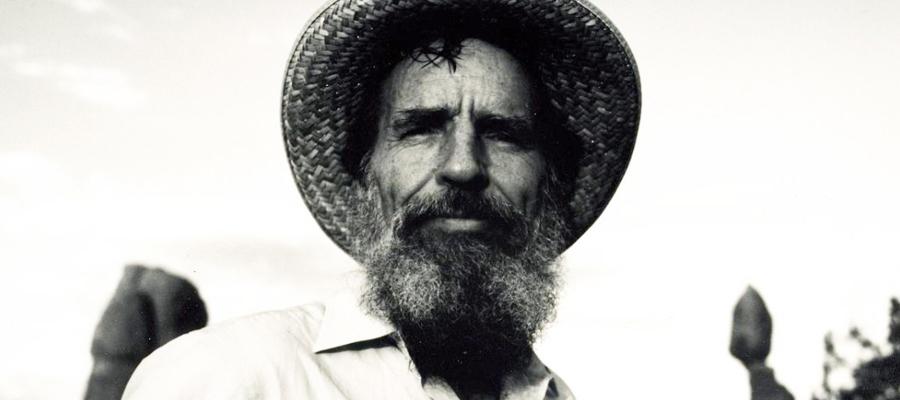

Clay visits with Edward Abbey, the colorful, eloquent, and passionate advocate of the American West

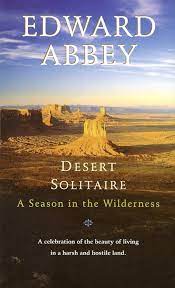

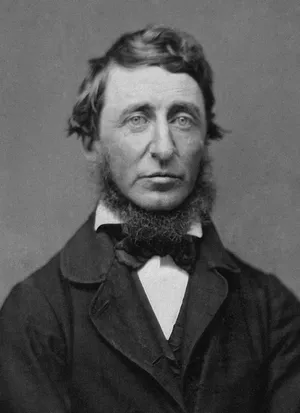

Edward Abbey — you won’t hear me calling him Ed, as if we played tennis together last week — has taken over my life. I’ve known his book Desert Solitaire for 30 years, and have read it half a dozen times, once just 10 days ago. Why? I’m conducting a humanities retreat in January at a lovely retro resort west of Missoula, and the subject is Thoreau’s Walden and Abbey’s Desert Solitaire — two curmudgeonly wilderness lovers who wrote their great books about a century apart.

Partly to get ready and partly to enjoy a rendezvous with some good friends, I’m traveling to Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, and Moab in early October as I return to my Travels with Charley Airstream tour of America. I haven’t been to Arches NP for ages, and the last time I hiked out to see the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers was with the best friend of my youth, Douglas, 30-some years ago now, maybe closer to 40. The ostensible reason for this Arches and Canyonlands adventure is to “get the feel” of Abbey’s world, to visit the site of the modest trailer he inhabited as a seasonal ranger near the old entrance of Arches National Monument (as it was known then). But whom am I kidding? What a great excuse for having three or four days in some of the most sublime landscapes of America. With friends who know how to appreciate. In the autumn, when children are back in school.

To prepare for the Utah adventure, designed to prepare me for the January Lochsa retreat, I’m reading well beyond the perimeter of Desert Solitaire (1968). I’ve read Down the River (1981). I’m reading through Abbey’s amazing journals: Confessions of a Barbarian. It is a poor title, which makes the common mistake of locking Abbey in as a monkey-wrenching anarchist. He is sometimes that, of course, the Abbey of southwestern legend, the Abbey who was the prophet of rage against the industrial machine. I admire that Abbey, but if you force yourself out of that alluring and reductive critical cul-de-sac, you discover that Edward Abbey is much more than a desert lands curmudgeon. He did some very serious reading in his life, and most of it was not memoirs of river rats and desert iconoclasts. He says he doesn’t like Shakespeare, but his books are filled with riffs on famous Shakespeare sentences. Here’s one I just read this morning. “The novel creeps along from day to day, a petty pace, lighting the way.” He’s talking about the slow progress of his first novel, Jonathan Troy, published in 1954. Abbey is riffing on a famous passage from Macbeth: “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day / To the last syllable of recorded time / And all our yesterdays have lighted fools / The way to dusty death.”

Does Abbey expect you to make the connection? Yes, maybe, but mostly no. He’s just having fun. Abbey’s ideal reader needs to know the geography of the Colorado Plateau, must know what it is like to float the whitewater rivers of the Southwest, must have read some Western philosophy (he’s no Thoreau dabbling in the spiritual traditions of the East), must know Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Bertrand Russell, whom Abbey adored. Must have read a good deal of Shakespeare, some Milton, some Keats, and some Wordsworth. But most readers then and even more now pass over these literary references, allusions, and riffs without recognizing them. This means they miss some of the literary exuberance and linguistic joy in Abbey’s writing, but it is not essential to find the echoes of T.S. Eliot (whom he pretended to despise) in order to get a full-ish appreciation of his work. But his literary legerdemain lights me up, I can tell you that. But I don’t know Canyon Country well enough to appreciate Abbey’s books fully. I’ve not been to Rainbow Bridge. I’ve not floated the San Juan. I’ve not spent months alone in a fire tower overlooking a New Mexico forest. I’ve never spent a night in jail for vagrancy. Everyone brings to Abbey what they have in stock — travels, books, adventures and scrapes, conversations, politics, love affairs, and reading. Nobody brings enough. He was sui generis.

Here are some things I have learned from reading around Desert Solitaire.

1. The journals indicate that, like Thoreau, Abbey combined several years of experience at and around Arches National Monument into one sustained seasonal narrative. Thoreau combined his two years, two months, and two days (1845-47) into one “season” at Walden Pond. He admits this freely. Abbey is a bit more coy about his literary strategies. More to the point, he doesn’t bother to inform us that his wife Rita and their first child Joshua were with him during his second season as a seasonal ranger at Arches. To have revealed that would have damaged the book, and the title Desert Solitaire would have been a problem. This leads to insight number two.

2. Abbey was married five times, fell in love 20 or more times, and pretty much slept with any woman he could lure into bed, usually but not always furtively, to avoid as much marital strife as possible. Each of his wives knew that he slept around in an obsessive, addictive way. His super-intense womanizing damaged the people who loved him best, including the five children he fathered and mostly neglected along the way. His journals are so obsessed with sex, so frank in a Boswellian way about his inability to keep his zipper up, that it becomes a little tedious, and any 21st-century reader, male or female, must lose some respect for him in the process. Think of all the pain he sprayed around like an old billy goat. I say old because he was invariably 10, 20, or even 30 years older than the women he married or seduced.

3. Abbey was impoverished for much of his life, at times desperately poor, living-in-squalor poor, with one Dickensian landlord after the next threatening to throw him (and whichever wife or girlfriend he was with, plus children) out on the street. He had to move all the time until the proceeds of Desert Solitaire (1968) made him economically comfortable. He led a sad Grub Street sort of life because he regarded himself as a novelist, but his gift was for creative nonfiction, and he resisted that Muse for several impoverished decades. Again, I think of the “cost” to his women and children, living like Wilkins Micawber in David Copperfield, constantly scratching to make rent and hoping “something will turn up.” Like his contemporary Jack Kerouac, Abbey got famous almost too late. Kerouac was in the deep trough of embittered alcoholism by the time On the Road changed everything in 1957, and by then, for him, it was too late. Abbey did somewhat better in this regard. He was a hard drinker but never an alcoholic, and — as the son of the latter and the friend to many of the former — I can attest that there is a world of difference. In reading the standard biography by James Cahalan and in reading his journals, I fret for him. I hate to think of a genius living hand to mouth. I feel sorrow that his gift was not recognized sooner. But it was mostly his fault for believing the novel was his genre.

4. For all the anarchic theater and the bluster and the crude philandery, Edward Abbey was a serious, at times deep, thinker. He had a huge, sensitive, and thoughtful soul. That’s why Confessions of a Barbarian is so inept a title. The selection of journals published by David Peterson, one of his friends and admirers, embraces about a quarter of the 20-some journal notebooks Abbey kept from 1946 to just weeks before his death in 1989. Of course, the Abbey of American mythology has a place in the journals, but only a modest place. Most of what he wrote in those fascinating, at times gripping journals might be called self-excavation: why do I betray the women I love and drive them away? Do I really enjoy solitude as I so loudly proclaim, or am I lonely in desperation when no comely woman is hovering somewhere in the zip code? What makes for a good book? What makes for a good novel? Am I as talented as I think, or am I dead mediocre? What should I do if it is the latter? Why are my children wary of me? Do I love the desert as much as I think, or is it, in some regard, a pose?

5. The Abbey who emerges from the journals is richer, deeper, more nuanced, more reflective, more widely read, more uncertain of himself than the persona he crafted into a Western legendary figure: the man who will light a tire on fire and roll it over the brink of the South Rim of the Grand Canyon; the man who throws his beer cans out the pickup window; the man who trades witty insults with overweight tourists at the Arches entrance station. The non-legendary Abbey is, to me, more interesting than the figure of American myth. I’ve marked hundreds of passages from the journals but only a few dozen in Desert Solitaire (which I love).

My favorite Abbey is the Abbey of the river journeys. There is a great one in Desert Solitaire with Ralph Newcomb. My favorite is Down the River with Henry Thoreau, but I am going to criticize it just a bit. It could have been one of the great essays of our time — but it is just really good. Who better to carry a greasy, tattered copy of Walden down Glen Canyon and write about the insights, the magic, the quirks, and the frustrations of Henry David Thoreau? Much though I love it, the Glen Canyon essay has the feel of being pretty quickly assembled without really probing into the heart of Thoreau’s genius. Abbey is mostly bewildered by Thoreau’s chastity — and has a hard time loving him wholly, given Henry’s abdication of the fundamental carnality of humanity. He is not quite sure a celibate could be wholly admirable. Like his river essay, Down the River with Major Powell, it feels more assembled than thought through. I very much admire Abbey’s Running the San Juan, which contains a perfect description of a playful water battle among the floaters, which ends this way: “the battle fades, the swimmers struggle back into their boats. The sun blazes down and we begin at once to dry out; the evaporating cooling effect, in this intense heat, is double refreshing.”

That passage could not be improved upon. Anyone who has ever floated a river in a hot summer remembers the moment. There is nothing “literary” or “poetic” in what he wrote here; it is just muscular, direct prose without any Ciceronian flourishes that would damage the effect. His use of the word “struggle” is the genius of the passage. If you have ever struggled back into a kayak or onto a raft in a white water river, you know he chose the perfect word.

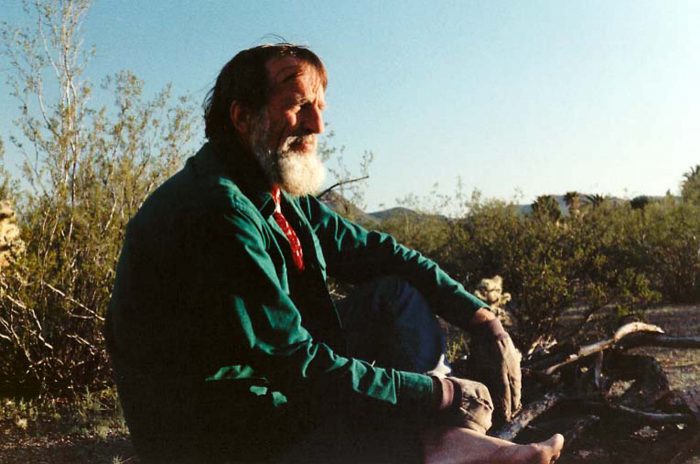

Abbey is a man of exquisite intellectual sensibility — perhaps a little undisciplined, as he would be the first to admit — which he successfully hid under the declarative rhetoric of Desert Solitaire. Ask a thousand people who was Edward Abbey. Most will say, isn’t he the guy who wanted to blow up Glen Canyon Dam? Something about monkey wrenching? Which is a good enough one-sentence characterization, but here are a few other possibilities.

-Edward Abbey was a lover of America’s wild places and a crusader to protect them from degradation at the hands of bulldozers and drilling rigs, but also from flabby tourists who wanted to carry their home comforts into all the places they visited and maybe dig up a cactus to put next to the bay window.

-Edward Abbey was an author who struggled to write the great American novel and knew by the time of his death that he had failed in that quest. Meanwhile, his nonfiction turned out to be his authentic voice. Still, it has been misunderstood as the expression of smart-aleck anarchy rather than the work of an exquisitely interested and complicated man.

-Edward Abbey had become a myth before he died in 1989. He knew this was humbug, but he loved it anyway because he had finally achieved fame and economic security, and even more women threw themselves onto their backs for him.

-Edward Abbey was a genius who envisioned a desert western utopia where people lived more lightly on the land, helped each other out, engaged in adventures and great conversations, where there was no class system and no industrial state.

-Edward Abbey was a thoughtful and sensitive man, a desert intellectual, who spent his life wrestling with the problem of industrial civilization.

If you didn’t know the source, who would guess that Edward Abbey wrote the following:

“Is Hamlet a tragedy? Or a muddle farce? A little of both, I would say, though a little more the latter. First thing, of course, the Christian metaphysical underlying the play has to be ignored; for how can death be taken seriously if it is merely the gateway to Hollywood? … since Shakespeare himself thought of Hamlet as a tragedy, and since most Englishmen have followed his suggestion, it seems obvious that, at least while watching or reading the play, most Englishmen have suspended their Christianity and taken death, not the doctrine of immorality, as something real and important.”

Or this:

“It is midnight in Edinburgh [what? Abbey lived in Edinburgh?] and I am haunted by a dim sorrow, a sweet sad gentle little anguish as soft and lovely and impossible to touch as the glowing coals in my fireplace.”

Or how about this:

“And the Enemy says, “Behold, how sleek and fat I have become. Am I not the wonder of the world? Am I not the richest and most powerful beast on earth? Would you turn against the thing which has enriched you, which has given you safety and security and comfort, which promises you still more wonders in the future — electronic toys, computerized thinking, a life air-conditioned from womb to grave, an existence of endless novelty, luxury, diversion, things and more things, a universe of sport and adventure and romance and travel in the softness of your armchair, the ease of your V-8 four wheel drive wheelchair tourism, the sedation of your living room? A painless, discreet, sedated death? And all this for so little, so very little—merely the price of some of your independence, a bit of your freedom, a little part of your manhood or womanhood, for only a little sacrifice of your humanity and honor.”

The major Abbey themes are here, but this is way beyond the snark and carp of Desert Solitaire (which I love).

I’ll keep reading up to and through my time next month in Canyon Country. I find Edward Abbey endlessly fascinating, and I am embarrassed that I had joined the chorus of typecasters until now. The breakthrough came when I decided to pair him with Henry David Thoreau to determine whether Desert Solitaire is a grumpy twentieth-century update on Walden. It wasn’t until I left the joyous confines of Desert Solitaire and considered Abbey through a wider lens that I started to understand his genius. If I were Abbey, I would say that the next time I hear someone who never met him call him Ed Abbey, I’d punch that person in the snout.

If I close my eyes, I can see him in public, lecturing in Boulder or Tucson or Barstow, bearded, rangy, denouncing and posturing, with vulgar and self-revealing asides, working the crowd into against-our-better-self ecstasy, then going drinking with a few new friends, including the woman he will convince to spend the night with him as the bar finally empties at 2 a.m. But it takes some serious and dedicated reading and musing to recognize how much more interesting he was when he was not in costume.