Day Seven, Thursday: Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

Clay Jenkinson and his colleges spent the day on the Hopi Reservation with Donald Dawahongnewa, learning about traditional dry farming practices and visiting the three Mesas that comprise the Reservation. This is the eighth in a series of dispatches from Clay chronicling his recent journey with two compatriots following the Colorado River and neighboring region exploring the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West.

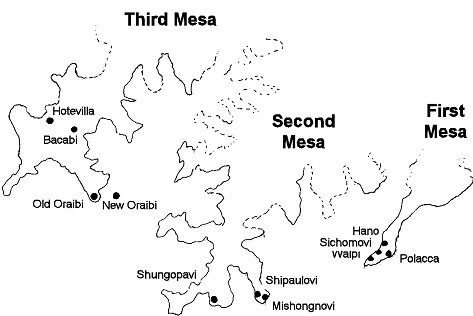

Snow was on the ground when we awoke on the second Hopi mesa. We feared a snowstorm, possibly a blizzard. We slipped and lurched to a remote coffee house that Dennis and Frank had scoped out the previous evening and then drove back to the Hopi Cultural Center, where we met Donald Dawahongnewa. Before long, the snow and ice had all melted, and a wan late-winter sun came out.

Donald Dawahongnewa is a humble Hopi farmer. His pickup had a problem, so he asked us to pick him up at his home in Shungopavi. We got a little lost, but he talked us in on his cell phone and stood outside when we rolled up. We took him back to the Hopi Cultural Center and moved toward the room where we did the interview. In the middle of a plaza at the Cultural Center, he stopped at a pyramid about eight feet high. He explained that this was a time capsule containing several objects and documents important to the Hopi people, erected in 1972 but not to be opened until 2072. Its purpose was to pass knowledge to future generations important to the Hopi people of the late twentieth century. Donald had been part of the group that constructed the time capsule, filled it with significance, and dedicated it.

We had been well-prepared for this interview by Paul Ermigiotti back at Crow Canyon, but Donald took us much deeper, in a humble and even nonchalant way. He described the traditional Hopi corn planting rhythms throughout a calendar year. He grinned from ear to ear when he said he hated the tractor because it had seduced many other Hopi away from traditional planting methods. I asked many questions about water; some he would answer, some not. He talked about the springs on the Hopi mesas — springs that were first discovered hundreds, even thousands of years ago.

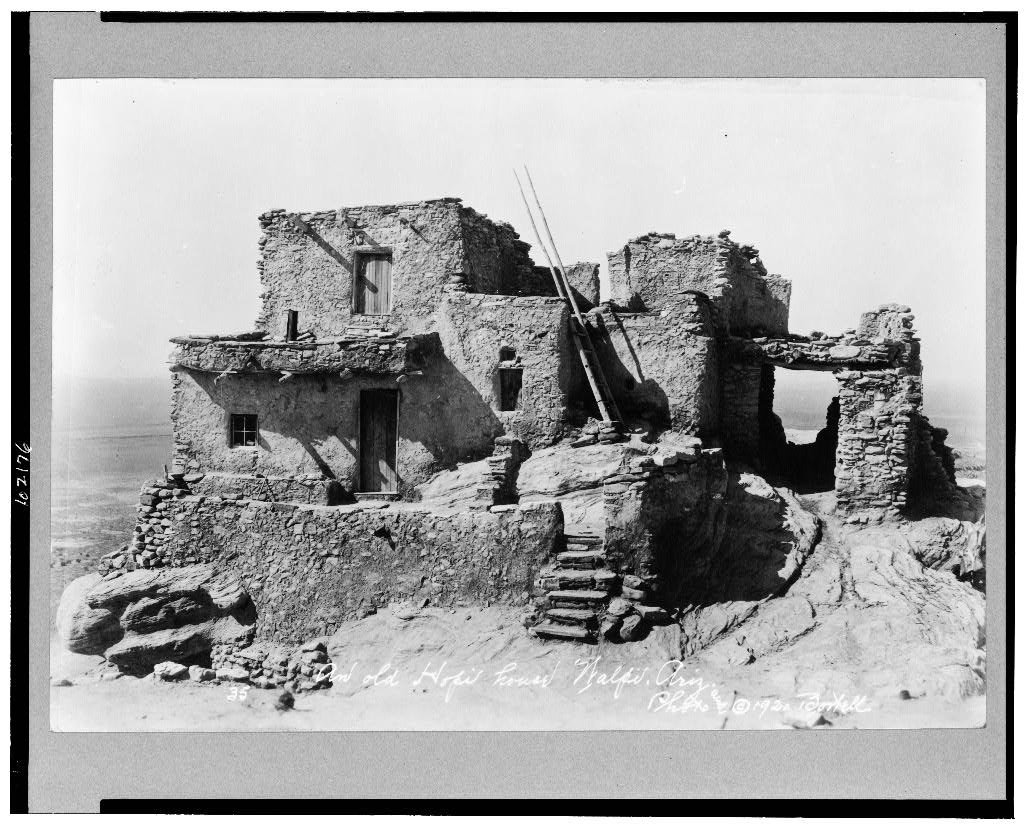

After lunch at the Center, he took us to several villages on the mesa. At some, we were welcome; at others not. Most villages had security checkpoints that linger on as the Covid 19 pandemic wanes worldwide. At one station, he assured the guard we would not get out of the vehicle. He took us to some of the oldest structures on the mesas and pointed out ancient and some recent kivas. He showed us one of the places where the great Pueblo Revolt of 1680 played out. It was as important to his sense of Hopi history as Valley Forge is to white Americans. When we drove past Walpi Village, I perked up in the backseat. Edward S. Curtis took several of his most beautiful portraits at Walpi. Donald would not take us there. He gave several reasons, but we sensed that he had sufficient but not disclosed reasons for remaining below.

It’s the 21st century, 400 years since the Pueblo Revolt. Yet here, in a very remote place in the Americas through which highways leave their threadlike trace, and most tourists are either unaware that there are villages on top of the mesas or are simply indifferent to their existence, an ancient people continue to pursue their lives. Donald and seemingly every other mesa dweller lived in what would be regarded as extreme modesty and a considerable amount of clutter in the white world. He has a pickup, a telephone, electricity, and running water. But he has these things in their more basic form. It feels not like poverty — though there is plenty of poverty here — but more like a deliberate choice to make as few concessions to the white materialist paradigm as possible. Not to eschew the comforts and amenities of modern American life but to keep them in their place. The agriculture Donald practices are unchanged since before first contact with the Spanish: the digging stick, the heritage seeds, the zigzag rows, the water rituals, the prayers and songs, the planting and the harvest festivals, the control of the seeds by Hopi women. He told us he knows it is time to plant when certain birds sing to him. He said strangers bring rain, which is why the Hopi are so generous to strangers. He said the Hopi hate war now and always and do everything in their power to remain at peace with everyone, no matter how serious the provocation. Clearly, if Donald did not have a truck, he would simply walk to his fields. You get the feeling that when American civilization collapses, when the faucets in Phoenix and Scottsdale run dust, when the highways break up, and the electrical grid goes down, these traditional Hopi will go about their business, shaking their heads at the newcomers who were so sure their ways and means were a permanent settlement of the American West.

The Hopi mesas are a little eerie and unsettling. Although there is a perfectly logical reason why a people would choose to live on plateaus high above the surrounding countryside, we still could not help wondering why a people would choose to live on top of mesas in the 21st century. There are hundreds of sizable mesas in Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, yet most do not support inhabited villages. Of all the places we visited, I felt the least legitimacy in being there. It felt like another world within a world I thought I knew. I have spent time on the Lakota reservations in the Dakotas, the Absaroka and Flathead and Blackfeet reservations in Montana, and the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho, and though I always remember that I am a guest in another people’s sovereign land — the way I feel in France, for example — I nevertheless have the sense that I belong in those places. The Hopi world seemed a little forbidding to me. Now that I have been there, I want very much to return, see Donald again, be a little bolder with my questions, and find a way, if permitted, to get up to Walpi.

It was one of those days we won’t forget.

We were sorry to say goodbye, and he said he expected to see us again. We headed to Marble Canyon. By then the winds were so strong that they were shoving the big gray pickup all over the highway. Or maybe it was just Frank’s driving.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.