While John Steinbeck was not much interested in National Parks, he traveled through a nation whose conservation footprint was indelibly shaped by a visionary Iowa Congressman.

Steinbeck confessed that he was not particularly impressed by “the spectacular, the astounding — the greatest waterfall, the deepest canyon, the highest cliff, the most stupendous works of man and nature.” He said he would rather gaze at a photograph by Matthew Brady (1822-1896) than at Mount Rushmore.

John Steinbeck was not much interested in America’s National Parks. He said he dipped down into Yellowstone National Park merely to forestall criticism from his friends. He wrote (in Travels with Charley) that if he drove through Livingston and Bozeman, Montana, and didn’t visit America’s first National Park (1872), they’d load him with recriminations. The Yellowstone visit proved abortive when his French poodle Charley went berserk when he saw his first-ever grizzly bear through the window of the GMC pickup. Steinbeck saw some primordial savagery in Charley he had never seen before and didn’t think possible. So, the great novelist immediately left the way he came, abruptly, and without remorse. No Old Faithful for John and Charley Steinbeck.

Yellowstone was his only National Park on the Travels with Charley trek. He did not stop to take a look at the Grand Canyon. He did not visit Bryce Canyon National Park or Zion or Big Bend or Great Smoky Mountains. He kept moving, on the best roads America had at the time, though few then were Interstates. Steinbeck did not share William Least Heat Moon’s obsession with blue highways, the narrow asphalt roadways that connect America’s small towns like a string of kitschy pearls. For most of his transcontinental trek Steinbeck was in a kind of slow-motion hurry — from third wife Elaine encounter to the next Elaine encounter. He does not mention museums, interpretive centers, the world’s largest this or that, or the site of this or that famous battle. Except for a brief visit to the Little Bighorn, which he described (and dismissed) in a single paragraph.

Steinbeck said he undertook his great 1960 journey “in search of America.” He confessed at the beginning of Travels with Charley that he had lost touch with the people of America who did not live in New York or San Francisco. He believed his creative mojo had ebbed to a dangerous level and he was living on the fumes of his once-great talent as a writer. He wanted to reconnect, to listen, to fill the tank of creativity. In the autumn of 1960 John Steinbeck drove America (some 11,500 miles worth, around the perimeter) and the book he wrote about that journey is full of interesting observations about the homogenization of American language, food, and style; about the coming of fast food and mobile homes; about the sterile triumph of plastic; about the litter and junk heaps that line many of the nation’s roads; about the reluctance of the American people he met to talk about current events, even in a consequential election year. But he did not stop to see much along the way. Diner to diner, motor court to motor court, gas station to gas station (when they sold little more than gas, candy, and cigarettes). Elaine to Elaine.

He had a couple of dozen important encounters with people along the way. His sons John and Thom later said they didn’t believe he really talked to anyone out beyond New York City, in part because he was a shy and private man. Maybe so, but I think his sons exaggerated, partly because they carried some pretty deep skepticism about their famous father, whom they didn’t know very well. The greatness of Travels with Charley is really about those periodic encounters — with the Canadian potato growers at the top of Maine; with the itinerant Shakespearean actor in eastern North Dakota; with a young gay man in northern Idaho who aspired to be a hairdresser; with several individuals (black and white) roiled by the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South.

And Charley, of course. Take Charley the haughty but lovable French poodle out of the picture and Travels with Charley is not much of a book. Charley, not Steinbeck, is the star of the story and the whimsical cur managed to get his name into the book’s title. Whenever Steinbeck is in danger of getting ponderous in his assessment of America in 1960, Charley reclaims the journey with his signature gap-toothed “ftt.”

Look Homeward Author

After confirming in Monterey and Salinas, California, that Thomas Wolfe was right in declaring “you can’t go home again,” Steinbeck said goodbye to his wife Elaine, who had joined him from Seattle to Monterey Bay and would next meet him on a ranch near Amarillo in the Texas panhandle, where they spent Thanksgiving 1960. His old friend Toby Street rode with him and Charley in the pickup across southern California to Flagstaff, Arizona, where apparently Street decided he had enough of truck camper life.

By the time he turned Rocinante around at Monterey Bay and began the long journey back to New York (and home), Steinbeck admitted that he had run out of steam. “Starting on my return journey, I realized by now that I could not see everything. My impressionable gelatin plate was getting muddled. I determined to inspect two more sections and then call it a day — Texas and a sampling of the Deep South.”

Steinbeck must have driven along Route 66 toward Albuquerque and Amarillo. He wrote, “I know this way so well from many crossings — Kingman, Ash Fork, Flagstaff, with its mountain peak behind it, then Winslow, Holbrook, Sanders, down hill and up again, and then Arizona passed.”

Petrified Forest National Park

I spent a night recently in Holbrook, because I have always wanted to visit Petrified Forest National Park. We have a petrified forest in western North Dakota, in the south unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Ancient Cypress trees turned like Lot’s wife to stone, 50 million years old. I take visitors there as often as they will agree to it. I like North Dakota’s petrified trees all the more because you have to walk well more than a mile to get to them. They are not just lined up by the side of the road for the tourist’s convenience.

So I ditched the Airstream at an RV site in Holbrook and drove to the south entrance of Petrified Forest National Park. Once in, I saw desert country in every direction, Edward Abbey country, blue-gray far distant mountains to the West. Thanks to my geezer pass ($80 forever, available when you turn 62), I passed quickly through the entrance kiosk and drove to the museum and interpretive center. Then I strolled over the .3 mile loop trail just west of the museum and took photographs of petrified tree segments. They are amazing to look at and to contemplate. These trees fell into swampy water several hundred million years ago. They were covered with silt. Silica and other minerals slowly replaced the organic matter — essentially cell by cell — to form an exact simulacrum of the tree, lifeless, but amazing. A fossil tree. They always fill me with wonder, except when they are dropped as ornaments in people’s driveways.

It was a hot day and I had miles to go before I slept, so I didn’t linger long among the rock forest, which has the feel of a rock garden.

I have the following observations about Petrified Forest National Park.

— I hope this doesn’t sound callow, but when you have seen a hundred petrified trees you have pretty much seen them all. No, this is not strictly true. The petrified cypress sections in the badlands of North Dakota are white and gray. The petrified trees in Arizona are a deep brown-red, and some of them have astonishingly beautiful crystals embedded in their trunks. The fragments in Dakota are short — none more than 10 feet in length, most about half that length or less. The petrified trees in Arizona are long, not always intact, but in many cases the segments line up. They cracked into segments well after the petrification was complete. A few are more than 150 feet in length. At first glance, the petrified forest in Arizona looks like a dense, above-ground fossil tree cemetery. It’s overwhelming. But after 45 minutes or so wandering among them, their capacity to maintain your sense of wonder begins to fade a bit.

— People must try to abscond with chunks of petrified wood, picked up in the National Park because there are stern warning signs everywhere and when I left the National Park by way of the north entrance, all cars were required to stop for “inspection.” The ranger waved me through. I must not have fit the profile. Or maybe he glanced into the crowded cab of my pickup and reckoned it wasn’t worth the trouble. This reminded me of the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz movie, The Long Long Trailer( 1954), in which Lucy collects large rocks throughout their journey and stores them in the interior of the long long trailer. Since they are massive and round and not tethered down, her volleyball-sized boulders wreak havoc throughout the interior. Ricky is not happy (never was outside of the Tropicana) and as usual Lucy has some ‘splainin’ to do.

I took nothing but pictures, left nothing but footprints in Petrified Forest National Park.

The Indelible Legacy of Congressman John Lacey

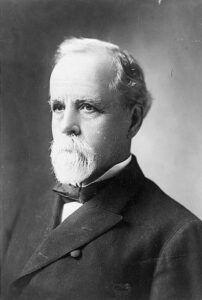

Not far from the north entrance I stopped at a magnificent vista called Lacey Point. I know this Lacey! John Lacey (1841-1913) is an incredibly important figure in the history of American conservation. He was an Iowa Congressman. Born in West Virginia, he moved with his family to Oskaloosa, Iowa, in 1855. He fought for the Union in the Civil War. Then he studied law. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives for eight terms (seven sequentially). In 1902 he was inducted into Theodore Roosevelt’s Boone and Crockett Club. For 12 years he was the Chairman of the House Committee on Public Lands.

But that’s just his resume. Lacey’s name is attached to three monumental pieces of congressional legislation.

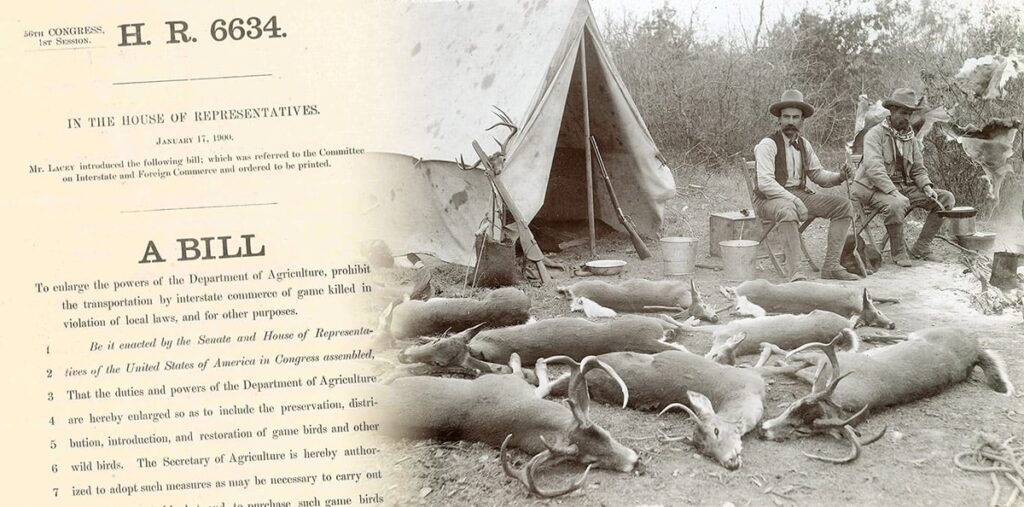

First, the Lacey Act of 1894. Thanks to his leadership, Congress gave the Department of Interior the power to arrest and prosecute poachers in Yellowstone National Park. This was the first time the United States created a mechanism to prevent trophy and commercial hunting in Yellowstone and — by extension — the National Parks generally. The Lacey Act of 1894 helped to formulate the conservation principles for the entire National Park System, then and now.

Second, the Lacey Act of 1900. This was his greatest legislative achievement. This Lacey Act protects all the wildlife, plants and animals in America’s public lands by way of significant civil and criminal penalties for a range of violations. The act prohibited the sale or trade of wildlife, fish, and plants that have been appropriated from the National Parks. Once the bill found its way through Congress — thanks to the indefatigable efforts of Lacey and a few others — President William McKinley signed it into law.

Third, the Lacey Act of 1907. This one made it possible for the federal government to allot tribal funds to certain classes of Native Americans. At a time when U.S. government policy was determined to “kill the Indian, save the man,” as the father of the Indian Boarding Schools Richard Pratt phrased it, Lacey’s compassionate leadership made it possible for the government to do something for America’s indigenous people rather than to them. That bill was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt, who was a close ally and admirer of Lacey.

And then there is the Antiquities Act of 1906. Lacey was co-author of this monumental piece of legislation, which permits the president to unilaterally designate (without the participation of Congress) parcels of public land deemed to have archaeological and historical importance. It would be impossible to exaggerate the importance of this legislation. Think of Aztec Ruins (New Mexico), Devils Tower (Wyoming), Montezuma Castle (Arizona), Canyon de Chelly (Arizona), Craters of the Moon (Idaho), Dinosaur (Colorado & Utah), Fort McHenry (Maryland), Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad (Maryland), Little Bighorn Battlefield (Montana), and scores of others. And more recently Bears Ears (Utah), Grand Staircase Escalante (Utah), and Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley (Illinois & Mississippi).

Few presidential powers are as unchecked and sweeping as the authority granted under the Antiquities Act. If Joe Biden (or soon, Donald Trump) wishes to carve out a National Monument in the middle of Montana’s public lands, he has a virtually unstoppable right to do so. A piece of legislation so enlightened and impactful would stand no chance of passing Congress today. In fact, it’s more likely that today’s Congress would try to limit or abolish the Antiquities Act.

A number of the National Parks began their existence as National Monuments: Grand Teton (Wyoming), Bryce (Utah), Zion (Utah), Olympic (Washington), Acadia (Maine), not to mention Grand Canyon National Park that began as Theodore Roosevelt’s Grand Canyon National Monument, at more than 800,000 acres. (The Antiquities Act was intended to protect small parcels of 5 to 25 acres, but Roosevelt characteristically read the legislation in the most expansive and empowering manner.)

All national monuments are created by executive order! The most recent is Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni-Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument, established by President Biden in August 2023. It embraces 917,618 acres in Arizona.

When we think of conservation in the 20th century, we tend to think first of the great Theodore Roosevelt, who served a little less than two terms as president, but set aside 230 million acres of the public domain for permanent protection: five National Parks; 150 new National Forests (150 million acres); 18 National Monuments; 51 National Wildlife Refuges; and four National Game Preserves. Roosevelt’s achievement was staggering, and it changed the face of America, even the Idea of America, forever. Roosevelt had faults, but they must not be permitted to obscure his almost unbelievable achievements as the 26th president of the United States. It is impossible to conceive of his predecessor William McKinley giving so much of his political capital to conservation, equally impossible to imagine his successor William Howard Taft doing so.

But Roosevelt never visited most of the parcels he set aside for permanent protection. In every case, a large number of local and regional advocates worked tirelessly, often for their entire lives, to call attention to spectacular or endangered landscapes. It was their efforts which sent nominations of these parcels up the chain until they finally reached Gifford Pinchot, TR’s U.S. Forester, and Roosevelt himself. After Roosevelt, Pinchot, and TR’s trusted nature adviser George Bird Grinnell, nobody was more important in securing America’s public lands than John Lacey of Iowa — from a state mostly given over to till agriculture, not the most likely nursery of one of America’s greatest conservationists.

Unlike TR, Lacey had visited Arizona’s Petrified Forest and many other conservation properties in the American West. We owe him an enormous amount of gratitude. And he is the more interesting, perhaps, because unlike his celebrated friend in the White House, Lacey preferred not to call attention to himself for the great work he was doing.

As I stood there looking out on one of the most beautiful viewsheds in America, I was pleased that that vista was named for John Lacey. His leadership was explained in detail by an excellent interpretive sign; but I was chiefly inspired to think of what one person of vision, discipline, and perseverance can do to make life better for all the rest of us.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.