Clay visits Cedar Rapids, Iowa, boyhood home of pioneering journalist and author William Shirer, who later became friends with John Steinbeck.

As I made my way from Bismarck, North Dakota, to Long Island, New York, to visit John Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor home, I wanted to make several “humanities stops.” These include Pipestone, Minnesota, one of the most important pipestone quarries in North America; Mankato, Minnesota, site of the largest mass execution in American history; and Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, where Jefferson’s friends and proteges quarried mastodon bones to send him at Monticello.

Planning my initial itinerary with maps spread out before me and a copy of Travels with Charley, I decided to pilgrimage to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the boyhood home of William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Shirer is one of my heroes. His talent, drive, and some good luck made him one of the most important American journalists of the 20th century. After graduating from Coe College in Cedar Rapids in 1925, Shirer ventured to Paris in hopes of finding a job at an English-language newspaper and maybe writing the great American novel. He found work first as a print journalist and, soon enough, as one of the first of CBS’ Murrow Boys. With Murrow, Eric Sevareid, and a few others in March 1938, during the Anschluss (Hitler’s annexation of Austria), Shirer helped to invent the radio news roundup. His appearances on CBS radio, usually beginning with “This is Berlin!” were not as widely acclaimed as Murrow’s London rooftop commentary during the Blitz; nevertheless, Shirer was famous in America well before the U.S. entered the war in December 1941.

Shirer wrote more than a dozen books, including one of the best autobiographies of the 20th century, the three-volume 20th Century Journey. Volume two, The Nightmare Years, is one of the best books I have ever read.

John Steinbeck met William Shirer in New York not long before he (Steinbeck) traveled to Europe and North Africa in 1943 as a war correspondent. They met through a mutual friend, Lewis Gannett, the book editor for the Tribune. As he prepared to see the war for himself, Steinbeck sought out Shirer several times for advice about what to expect in war-torn Europe and how to report it. Shirer’s Berlin Diary was published in the United States in June 1941, at a time when most of the American establishment was skeptical of the horror stories coming out of Germany — the Gestapo, the SS, persecution of the Jews, the concentration camps.

The Complexity of Marriages

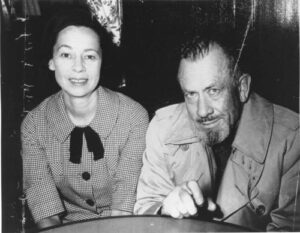

John Steinbeck’s domestic drama began unfolding at the same time. He was married three times. His first wife, Carol Henning (1930-1943), typed his manuscripts, helped him creatively, and named The Grapes of Wrath. She saw him through the lean and hungry years. After their divorce in 1943, Steinbeck selected his second wife on the rebound. He married aspiring singer Gwendolyn Conger in 1943. On the rebound — a leggy blonde with what observers called a “great figure,” a frustrated aspiring singer and actress, 20 years John’s junior, edgy about his celebrity. What could go wrong? In their five years together, Gwyn bore Steinbeck two children: Thom (1944) and John (1946). They divorced in 1948. In 1950, Steinbeck married Elaine Scott. They had most of two decades together. Elaine survived Steinbeck by 34 years. It was the happiest of the three marriages.

The second marriage was never really happy, partly because Gwyn convinced herself that she had sacrificed a promising stage career to become the wife of a selfish and famous novelist. But Steinbeck may have poisoned the marriage from the start by deciding, almost immediately after the wedding in New Orleans, that he had to get himself “into the war.” John and Gwyn were married in New Orleans on March 29, 1943. Just over two months later, he left for Europe. Gwyn was devastated. I think she never really forgave him for running off to war.

Desperate to keep her husband home during the honeymoon period of their relationship, Gwyn had visited Shirer secretly to convince him to dissuade Steinbeck from taking the assignment. Shirer refused. He told Gwyn that he understood John’s desire to get into the arena, contribute to the war effort, and not miss the greatest story of his lifetime.

Steinbeck embarked for England in June 1943. He took a typewriter, 4 quarts of Scotch, 2 pounds of pipe tobacco, and a hundred Multicebrin tablets (vitamins). Some of his war reporting was published as Once There Was a War in 1958. Steinbeck spent considerable time with William Shirer in London, partly, according to his biographer Jackson Benson, because Shirer “was of the breed of correspondent that is part scholar, part newspaperman.”

Readers of Travels with Charley know Steinbeck was carrying Shirer’s magnum opus, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, with the other volumes he packed in his truck camper. After a satisfying conversation in the rig with a local farmer in New Hampshire, Steinbeck wrote: “Charley looked after him and sighed and went back to sleep. I ate my corned beef hash, then made down my bed and dug out Shirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. But I found I couldn’t read, and when the light was off I couldn’t sleep.”

There is a mystery here. This incident occurred in late September 1960 in New England. However, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich was not published until October 17, 1960. How does John Steinbeck have a copy in his rig? There are only a few possibilities. 1) He’s making this up, perhaps because he doesn’t want to report that he was really reading Heidi or Old Yeller 2) He got an advance copy of the book before he left Long Island. This is entirely possible given Steinbeck’s friendship with Shirer and his celebrity. 3) He bought a hardback copy somewhere on the road when the book came out (Seattle? San Francisco?) and misremembered the sequencing when he came to write Travels with Charley. We have no way of knowing.

How to Read Travels with Charley in an Age of Disillusionment

At this point, I should explain my Travels with Charley methodology.

1. I believe that John Steinbeck really made this 10,000-mile journey in 1960, leaving Long Island on September 23, 1960, and arriving home sometime in December.

2. I believe he is reporting his itinerary accurately.

3. I believe every story or virtually every story in Travels with Charley is true, that every or almost every encounter and incident in the book happened during the trip.

4. Several writers, chiefly Bill Steigerwald, have proven (beyond any doubt) that Travels with Charley is not a book of punctilious fidelity to a kind of reporter’s “the facts and only the facts in precisely the right sequence” objectivity. It is clear that Steinbeck embellished his adventures and, I suppose, invented some of the dialogue. How could it be otherwise?

5. Steigerwald has shown beyond doubt that

- Steinbeck did not sleep in the truck camper as often as he would have us believe.

- Steinbeck’s wife Elaine was with him far more than Travels with Charley acknowledges. Steinbeck admits to meeting Elaine in Chicago for a couple of days of R & R (at a luxury hotel), in Seattle, and in the panhandle of Texas, where John and Elaine celebrated Thanksgiving on an opulent and ostentatious ranch to which Elaine had a connection. It’s not entirely clear how much of the time Elaine was with Steinbeck, but it comes close to 40%.

- Steinbeck tended to rush from one Elaine rendezvous to the next in such a way that he could not have been doing much searching for America.

6. I accept all of that, in substance if not with my friend Steigerwald’s gotcha tone. But I am not nearly so bothered by these discrepancies as Steigerwald. I’ve always accepted that Travels with Charley is the work of a literary master, not a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Steinbeck reminds us several times in the book that an author inevitably shapes his material. That to turn an adventure into a book requires structure, a beginning, middle, and end, and that the stories he tells in Travels with Charley — like all stories from the beginning of time — behave like stories — they get tidier, more dramatic, and more tightly structured as they are transformed from something that happened at the Maple River in eastern North Dakota into a usable incident in a work of non-fiction literature.

7. My default position, therefore, when I come upon a story, incident, or personage in Travels with Charley is that it is true, or I should say True in a higher sense. My default position is not — and this is where I chiefly break with Steigerwald — that the story is probably not true, that it was probably invented or so heavily embellished as to make it unreliable from the perspective of what a Steinbeck Cam would have revealed on that day.

8. Reporters should read Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech before embarking on this kind of investigative journalism. On that occasion, December 10, 1962, in Stockholm, Steinbeck reminded his worldwide audience that humans are fundamentally a story-telling species:

“Literature is as old as speech. It grew out of human need for it, and it has not changed except to become more needed. The skalds, the bards, the writers are not separate and exclusive. From the beginning, their functions, their duties, their responsibilities have been decreed by our species.”

9. Finally, where there are discrepancies or things don’t quite track or match up, my approach is to figure out what actually happened (where he actually slept and under what circumstances) and then to try to understand why Steinbeck was shaping the narrative as he did. For what literary purpose? The two easiest “distortions” to understand are a: that he exaggerated how often he really camped somewhere and slept in the rig sipping Scotch and reading under the light of a gas lantern and b: how often Elaine was with him in his travels.

Steinbeck wants us to picture him at the end of the day, parking under the trees in some quiet and obscure place on the backroads of America, heating a can of chili con carne, reading under the light of his gas lantern, sipping some smooth Scotch, letting Charley out for the last pee of the evening, writing a letter to Elaine, and making up his bed. It’s romantic and a little forlorn, with a bit of risk, a long way from the comforts of home. We’d probably be pretty dismayed if we knew exactly how many (or, as Steigerwald puts it, how few) nights he slept in his rig. Although he admits to staying from time to time in a “motor court” to have a good hot bath, he does not explain how often he wound up in a luxury hotel. That’s not the spirit of the quest.

The book would have been less satisfying if he had admitted how much he was with Elaine on the journey, how often he did not sleep in the truck camper, and how much he rushed to the next rendezvous site with Elaine. He was more candid in the original manuscript, now a treasure of the J.P. Morgan Library in New York City. But by the time the book went to press in 1962, Steinbeck and his editors had done what it took to cast the journey as a lone man’s adventure that ended almost every night in a camper bed converted from the dining table. He refused to eliminate Elaine altogether, but nearly so. This is what good authors and editors do to shape a story for publication.

I certainly don’t doubt that Steinbeck carried his friend William Shirer’s masterpiece for some at least of his 1960 odyssey around America.

And So to Coe College

So I made an appointment at Coe College to talk with their library staff about Shirer, one of the handful of the college’s greatest alums. The campus is beautiful. Coe’s Stewart Memorial Library has a splendid art collection, including a Picasso, a Matisse, and a fair number of paintings by another Cedar Rapids worthy Grant Wood. I was treated as an honored guest.

But no shrine to Shirer, not even a portrait (or a photograph) or, for that matter, a plaque. What a mistake! When Shirer graduated, Coe College president Harry Morehouse Gage, impressed by the young man’s talent and aware of his big dreams, gave Shirer a loan of $100 (about $1,785 today) and told him to go take on Paris and the world. Thanks to that act of inspired mentoring and faith, Shirer went on to write more than a dozen books, including the critically acclaimed and still widely read Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Shirer’s father died when William was just 9 years old. Raised by his widowed mother in provincial Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Shirer was lucky to be able to attend college at all, and thanks to big dreams, discipline, and drive, he went on to become one of the 20th century’s most successful journalists, as important to the ways of modern broadcast media as Edward R. Murrow or Walter Cronkite.

What could be a better student empowerment story than this? Or maybe they would all be demanding $1,785 upon graduation!

I lobbied hard for Coe to do justice to Shirer — with the usual result. So far.

Because Steinbeck knew Shirer and because he carried with him a copy of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich in his rig, I’m carrying the book, too. I first read it when I was 15. It was one of my father’s favorite books, and he urged me to read all 1,249 pages. I did. Much later, I portrayed Shirer in the Great Basin Chautauqua. I suppose I have read it five or six times over the years, and it never ceases to live up to one’s great expectations.

It would be a small but important contribution to Steinbeck studies if I could solve the mystery of how he seemed to have with him a book that had not been published by the time he said he lay awake reading it. An audio interview between Shirer and biographer Jackson Benson, housed at Stanford’s Green Library, may hold some clues. My friend Russ Eagle has ordered a digital copy. Stay tuned.

Over the next few months, Clay will shadow Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and make a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures and subscribe to our newsletter.