Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

This is the seventh in a series of dispatches from Clay Jenkinson chronicling his recent journey with two compatriots following the Colorado River and neighboring region. The day was spent at Canyon de Chelly on the Navajo Nation. The two-week expedition explored the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West.

The writer, Timothy Egan calls Canyon de Chelly “the garden spot of Navajo land, where rock, sun, wind, water and the ages had produced one of the world’s singular places.”

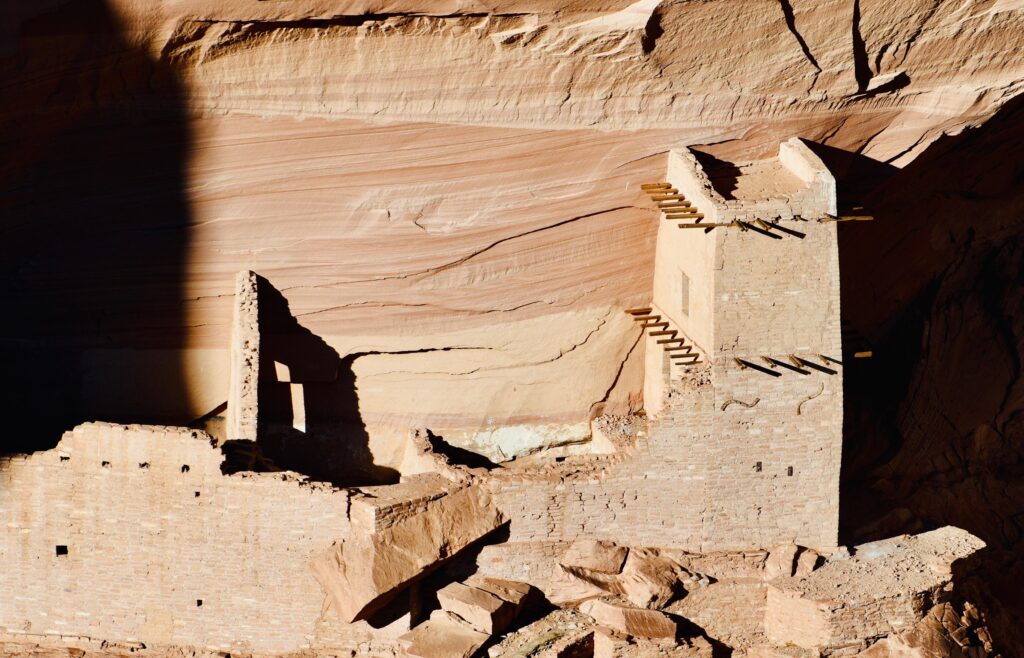

Canyon de Chelly is one of America’s most magical places. I first visited it 35 years ago with my closest friend Douglas. We were traveling from southern California to Colorado Springs, and we detoured a few hours to see it. I remember being overwhelmed with awe: the green cottonwood trees embraced by the pink and red canyon walls; how contained, almost miniature the canyon is, the elegance of the ruins, the desert varnish. It had an air of mystery about it then that I didn’t feel this time through. You can only see Canyon de Chelly for the first time once. As you can only read Hamlet for the first time once.

The canyon is hidden, and you come upon it from above with such suddenness, and its twin reaches are so modest in length (30 miles) and remote that Canyon de Chelly is essentially a magic portal into an alternative America. It doesn’t have the depth or the grandeur of the Grand Canyon. It doesn’t overwhelm you as much as it seems to invite you to hide out from the world. It feels mystical. Hampton Sides writes, “It was, the Diné believed, protected by supernatural powers no white man could touch.”

Part of me wishes it were still hidden away and only the Navajo and the Hopi knew of it. I’m with John Muir that some places in America should be protected forever from economic intrusion — that some places should never be visited by humans unless they hike in over a series of days with a minimum of gear. This place maybe should be off limits to non-Natives. It was a sanctuary rudely violated by the U.S. Army in the 1860s and ’70s. Sides writes of this tragic episode, “In their heart of hearts the Diné had always regarded Canyon de Chelly as their last stronghold and sanctuary, the one place where they felt truly safe. When their wider world was in turmoil, when they could find no relief from pestilence or harrying foes, they had always fallen back here, to hide in the timeless folds.”

We not only wrested the Indigenous people out of the canyon, but did everything in our power to disrupt, destroy, and desecrate one of their most sacred places. Why? What did we have to gain? This is not the island of Manhattan or the shore of Lake Michigan. Why did we have to conquer it and cut its life throat?

The name de Chelly is a Spanish garbling of the Navajo word Tsegi, “rock canyon.”

I did not know back then when I first came here that the U.S. government harried the Navajo relentlessly, especially in 1864, defeated them in their canyon redoubts, and hustled them off to a truly wretched reservation at Bosque Redondo. Mountain man and scout Kit Carson was tasked with flushing the Navajo out of Canyon de Chelly. He expressed his reluctance and then did what he was expected to do. As he undertook his campaign, Carson assured his commanding officer James Carleton, “Of one thing the General may be assured … before my return, all that is connected with this canyon will cease to be a mystery. It will be thoroughly explored [with] perseverance and zeal.” After he defeated the Navajo in a series of small skirmishes, he ordered his subordinates to “lay waste to everything: every hogan, every brush arbor, every animal, every store of grain. It was to be more scorched earth, in other words, only this time the work was to be carried out right in the high church of the Navajos,” as Sides puts it.

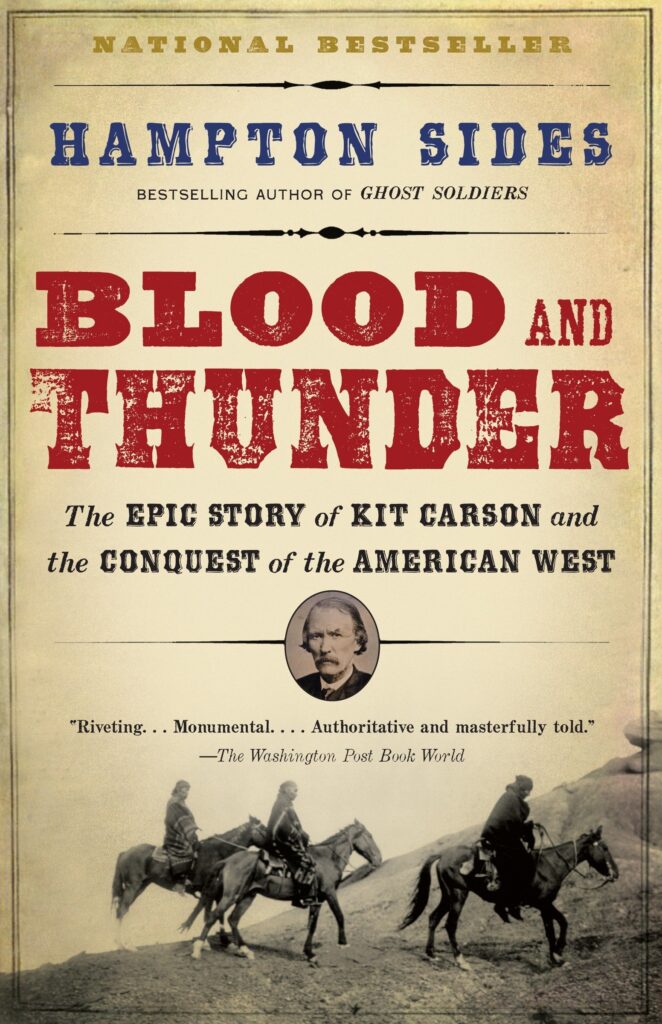

Among other things, Kit Carson had his men cut down and burn literally thousands of the Navajo’s peach trees in the Canyon. Although this was nothing as horrible as his killing of any Navajo who resisted, Carson’s willingness to cut down all those fruit trees somehow carries a special moral opprobrium. It feels like an atrocity. Eventually, the Navajo were permitted to return to their ancestral homeland by way of what is remembered as “the Long Walk of the Navajo,” but when they arrived, they had to start from scratch in their orchards. The U.S. government, having appropriated or killed off the Navajo’s great sheep herds, now provided a modest new starter herd. All of this is superbly handled in Hampton Sides’ book, Blood and Thunder: The Epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West.

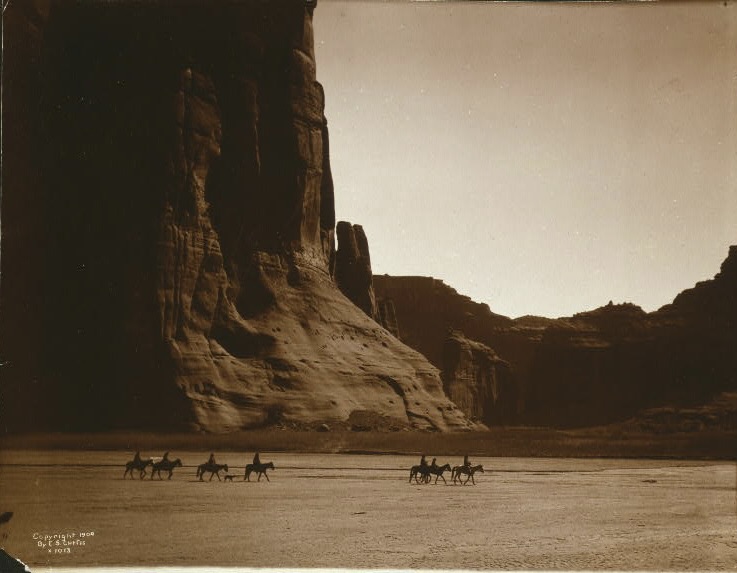

What struck me on my most recent visit is the preciousness of water. Because it has been a wet winter in the West, all the creeks are running, and the streams, and the Chinle Wash at the bottom of the canyon. Running water in a desert country is lifeblood in a way that cannot be exaggerated. And it is better felt than described. We were fortunate to be visiting at a time when the earth was flush with the flow of lifegiving water. Everyone we met in the canyon was in a good mood. Water is life. When the canyon is bone dry, it can feel like an oven. The dust whips up with the wind. In a parched August there is a kind of lunar serenity, but not much life stirring. But let the wash run like a river, slosh around in it in childlike joy, and all the life in the canyon begins to stir. A big year like this can make up for a prolonged series of dry years. Most of America can afford to take water for granted. Turn on the faucet, out comes clean potable water. We regard water as an entitlement, a taken for granted fact of life. But out in desert country, water is something you never dare take for granted, even in a wet year like this. Edward S. Curtis visited the canyon twice. He loved its peacefulness and serenity.

Touring the Canyon

After breakfast we paid our fee and joined a tour group in three-axle Austrian vehicles. We three joined two couples, one of which appeared to be the sort of earnest senior citizens who travel America in search of enlightenment. The other couple was late. They had flown in that morning in a private plane solely for the purpose of seeing the canyon. I wanted to dislike them for their wealth and sense of entitlement, for keeping us waiting, but the canyon was so magical that I couldn’t stay grumpy very long.

We got off the gear-grinding vehicle a couple of times to pee and stretch. I bought a lovely vase from a shy Navajo woman. When I said I was traveling she shouted across the wash for another woman to bring a box and something to stuff around the fragile vase. All this in one of the most isolated places in America.

At the time of our visit, the canyon floor was a real river. We splashed or slogged through it several dozen times on the four-hour tour. Early on, an identical vehicle ahead of us got stuck in the wash — quicksand is everywhere and unpredictable we were told — and another vehicle had to winch it out.

Our Navajo guide stopped six or seven times during the tour. He pointed out ruins we might otherwise have missed. He used a pocket mirror as a pointer to show us rock art, and to trace the outline of giant figures etched into the sandstone walls. I asked about the location of several of the famous photographs taken in Canyon de Chelly by Edward S. Curtis. Our guide said the location of the photograph of the horsemen moving slowly through the canyon was currently inaccessible because of the high water. I showed him a greeting card we had purchased in the motel shop of the photograph in question. He shrugged. It did not seem to me that the work of Curtis was one of his concerns. And he was right. Satisfying as it was to us to visit the canyon in the footsteps of Curtis, and to try to line up his famous photographs with the contemporary landscape, we were mediating the experience. Instead of just drinking in Canyon de Chelly in all its challenging sacredness, we (mostly I) were grooving on the work of a white man who turned up in 1904 as he lived and worked among the Diné.

Why did I feel uneasy in the canyon and wonder if it should not be off limits to white people? We venture in, spend a bit of time, leave behind some money, take some photographs, buy a souvenir, and venture out again. In a certain sense we were privileged white people having our way with Canyon de Chelly. If the Euro-American history of the American West is the history of exploitation and extraction, weren’t we more squarely in that tradition than is comfortable to contemplate? Weren’t we extracting pleasure and a kind of cache of virtue by going there? I have noticed over the years that when people talk about visiting Canyon de Chelly (I am one of them), they lower their voices a little because it means they belong to a special club. It’s a much greater mark of enlightened travel than, say, Yellowstone or Yosemite. Saying you have visited Canyon de Chelly carries a bit of virtue signaling.

Even a cursory reading of the history of the place reveals that it was a profound sanctuary for the Navajo. It was and is one of their most sacred places. Even with the vehicular limitations now observed in the canyon and a touring price that was not inexpensive, there was a lot of roar and rumble on the canyon floor. In four hours, we saw scores of pickups. We could only get through the saturated gravels of the wash with extremely powerful industrial vehicles. It felt a little like we were part of an Indiana Jones movie. Our guide was clearly bored with us. We were, of course, just group x. In fact, when he dropped us off back at the motel, the next tour group jumped right into the vehicle and off they went for the two o’clock.

What have I done to deserve to penetrate this sanctuary? In what sense do I deserve to be here? You can say that we visitors bring much needed income to the Navajo. You can say that choosing to come here and not Disneyland indicates something good about our values and priorities. You can say that calling attention to the nineteenth century desecration of the canyon and the conquest of the Navajo can contribute to a new understanding of the history of the American West. But what really have we done to earn this experience? We drove into Chinle in one of the finest machines western civilization can produce. Then we rumbled through the canyon in a specialty vehicle designed for difficult terrain. Somewhere in Dakota or Texas or Saudi Arabia an oil well bought us our tickets. In the course of the day, we did not walk more than 200 yards. If we had had to walk into the canyon in waders, five, then, twenty miles, would we have done so? If the canyon was only available by horseback, would we have spent the day in the saddle?

Aren’t we in some way still occupying Canyon de Chelly? Isn’t our very presence disruptive and disturbing? When it became a National Monument by executive order in 1931 (Herbert Hoover), were the Navajo consulted, compensated, considered? If, as we learn from the administrative history, President Hoover made it a national monument to preserve the ancestral pueblo ruins from poaching and pot hunting and vandalism, did that necessarily imply that it should become a tourist destination, too? The monument was closed during the pandemic. I try to imagine the serenity of those 477 days. Think of how many critters came down into the wash to drink.

Don’t get me wrong. I loved my second visit to Canyon de Chelly. And I would probably visit it again. But it felt a little violative.

When we got back to the lodge, we piled into the pickup and headed towards the Hopi mesas.

A Final Note: Writing (and Reading) American History

One last note. In the months before our visit, I read two books about Kit Carson, Hampton Sides’ Blood and Thunder (mentioned above) and Stanley Vestal’s Kit Carson: The Happy Warrior of the Old West. Sides’ book was published in 2006. He’s entirely a product of our time — especially sympathetic to Native peoples and the environment. He would not have written a full-length book about Kit Carson if he were not fascinated by the mountain man, explorer, scout, Indian agent, and Indian fighter. And there is a great deal to admire in Carson. He got the somewhat bumbling John C. Fremont to South Pass and was as important as anyone for his success as the great white explorer of the mid-nineteenth century. My favorite Carson moment occurs in 1849 when he comes into the abandoned camp of Ann White who had been kidnapped on the Santa Fe Trail. Carson found a dime novel portraying the legendary “Kit Carson.” According to the New Yorker’s Jill Lapore, “White was killed just moments before Carson and his party reached her. Rummaging through the abandoned Apache camp where White had been prisoner, Carson found a copy of Averill’s just published ‘Kit Carson’; Ann White had carried it with her all the way from Missouri. ‘The book was the first of its kind I had ever seen, in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundred,’ Carson recalled, ruefully. ‘I have often thought that as Mrs. White would read the same, and knowing that I lived near, she prayed for my appearance and that she would be saved.’”

Stanley Vestal (1887-1957) was a prolific Oklahoma historian, the author of books on Sitting Bull, Jim Bridger, the Old Santa Fe Trail, and one of the classics of the Rivers of America series, The Missouri (1945). He was Oklahoma’s first Rhodes Scholar (1904). He was generally sympathetic to Native Americans, and he did hard pioneering work in Indian Country, including interviewing contemporaries and colleagues of the Lakota holy man Sitting Bull. But he was, like the rest of us, a man of his time. He devotes only a short final chapter to Kit Carson’s mayhem in Canyon de Chelly. There Vestal writes, “the conquest of the Navajo is unquestionably one of his greatest achievements.” He does not mention the slaughter of the quadrupeds of the canyon, and he never mentions the holocaust of the peach trees. He concludes his narrative with, “The Gibraltar of the Navajo was taken, and from that day they have been quiet, thrifty, law-abiding citizens, increasing in number and wealth from year to year.”

Two conclusions. First, thank goodness the historiography of the American West has evolved into a more generous, multicultural, culturally sensitive narrative over the last two generations. We all owe a great debt of gratitude to Patricia Limerick of the University of Colorado, whose revolutionary book, Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (1987) inaugurated a new era in our understanding of frontier history. Second, it is essential that we who study these things today respond to these paradigm shifts in history with humility rather than righteousness. Every generation is alert to some things and blind to others, and every generation tends to run the zeitgeist in which it comes to maturity. What will they say of us in 2075 or 2123?

We drove on to the Hopi Cultural Center on the Second Mesa.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.