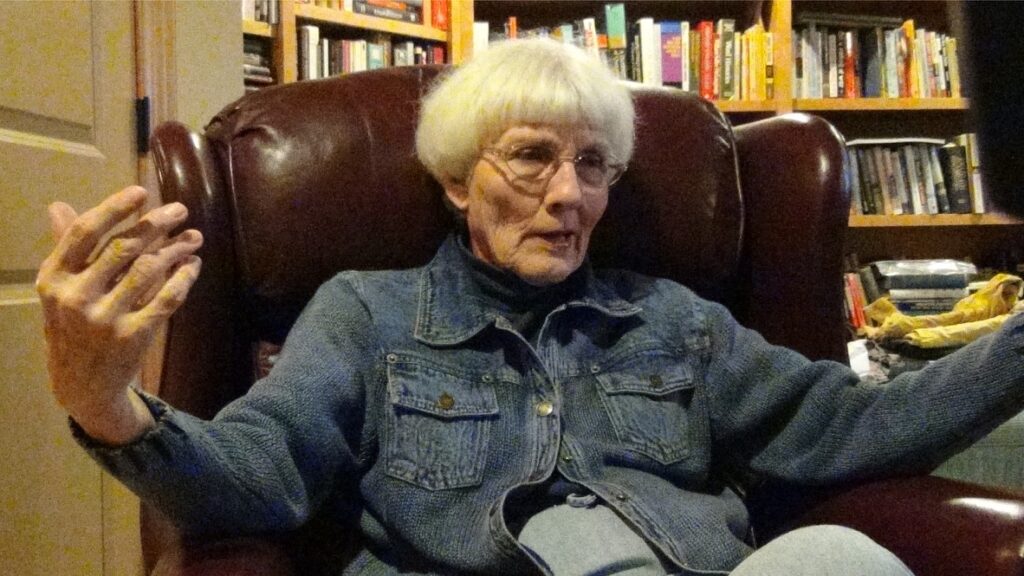

My mother has been dead for five years now. She died at 86, without spending a single night in a hospital. She always said she wanted to die with her boots on. My mother had a lifelong crush on westerns and cowboys. She taught “Westerns as Literature” at the public high school in Dickinson, North Dakota for 24 years, and she had been retired for that long, too. She died suddenly. In fact, I was out of the country when she died. She had intended to drive me to the airport for my trip to Britain, but she called that morning and said I had better take a cab, because she was feeling “punky.” I got the call at the British Museum. By the time I got home to North Dakota, she had been dead for a day. My daughter got to Bismarck about the same time, from New York. She looked like Eva Peron in her coffin.

Mother liked to be contacted on Mother’s Day, but she was not sentimental about such things. I always called and sent a card, and occasionally flowers. But flowers did not mean much to her. If I were close by, say within 200 miles, I would drive to Dickinson and spend the day with her. If I got there in time to go to church with her, she was genuinely pleased. As we left the church, where by now she was one of 40 surviving members, she would thank me in an explicit way. She was not worried about my salvation status. And she was not sorry that I do not routinely go to church. She just liked having me with her there once in a while. She knew that I would not have chosen to go to church if I had been alone.

Then she would make me a lovely Mother’s Day dinner. She was a master and a bully in the kitchen, so nobody was ever really allowed to participate. She’d say, “I’ll let you chop this onion,” or “I’ll let you take the garbage out, it needs it,” or “I’ll let you get out the big frying pan.” She’d make what she called Swiss Steak for me, with a salad and French dressing, some scalloped potatoes on the side and a vegetable. And she’d pour me a glass of white wine from one of a dozen open bottles of wine, white and red, in her back refrigerator. I would invariably say, “Mother, you know that wine is not like ketchup or vinegar, you can’t just expect half-consumed bottles of wine from New Year’s to be any good.” But she never adjusted this habit.

Whenever possible, I baked a pie for my mother for Mother’s Day. I think gifts that take some effort are the best. And she and I share a love of rhubarb pie. The first thing I did when I moved back to North Dakota in 2005 was drive the 300 miles to Fergus Falls, Minnesota, to my grandparents’ dairy farm, long since abandoned. There I dug up rhubarb from a long row of trees they had planted as a shelter belt. I regarded these rhubarb plants as my lares and penates of my new home. The ancient Romans had a little shrine at the entrance to their houses, and the household gods were placed there to protect the family.

So on the Saturday of Mother’s Day I’d go cut some rhubarb and make my mother a homemade pie. I can do good crusts. I’m not a great crust maker (I have known some), but I’m competent. Nor would I ever buy a grocery store crust. This was an area of dispute between my mother and me. She hated to roll out anything. She was not only beyond the period in her life when she would make a homemade crust, but in fact there had never been a time when she regarded that as a worthy pursuit. So, just to tease her a bit, I’d make my pie with a homemade crust. And the many imperfections in my crusts pleased her. In several ways, some of them positive.

Once she was in Bismarck (100 miles east) to spend the weekend with me. She wanted to drive home at mid-day on Mother’s Day because she had a hair appointment or something equally grave on Monday morning. So, I made our traditional family Sunday brunch — a cheese, onion, and green pepper omelet, ring sausage, orange juice, and toast. She invariably bought white bread, pre-sliced. She’d get out the butter tray for me — brown plastic, ca. 1965, and the special electric frying pan (why?), and she’d line up the first two slices of bread in their toaster slots. She’d pour us each a glass of orange juice in little repurposed dried beef jars. She always exclaimed over my omelets though they weren’t anything more than competent. And before she left town, we’d share a piece of rhubarb pie. Maybe with ice cream.

She loved that Mother’s Day pie. And it was a gift that really mattered to her, much more than some book I would have sent by way of Amazon.com or some kitchen gadget.

Two times over the years she wrote me an email the next day full of this and that, including gratitude that I had gone to church with her. And then she said (twice in non-consecutive years), “I have to confess that I sat down in the evening and ate the whole darn thing!”

I loved that. She was on the whole a temperate woman but when one of her appetites was aroused, she could devour a whole pie in a single evening, preferably watching something in which Tom Selleck starred. And later she’d say, “I had a good laugh over it.”

We were very good friends in addition to everything else. I’m glad she died in her late prime. I remember her in all her strength. Although the winter was very late here this year, I’m going to go out and check on my rhubarb supply, right after I make a slender version of the family memorial Sunday brunch.