John Steinbeck spent the night of October 12, 1960, in Beach, North Dakota, just a few miles from the Montana border. He was about to fall in love with Montana.

In homage to Steinbeck, I spent night one of Phase Two of my national John Steinbeck Travels with Charley tour in Beach, even though it is only 158 miles from my home in Bismarck.

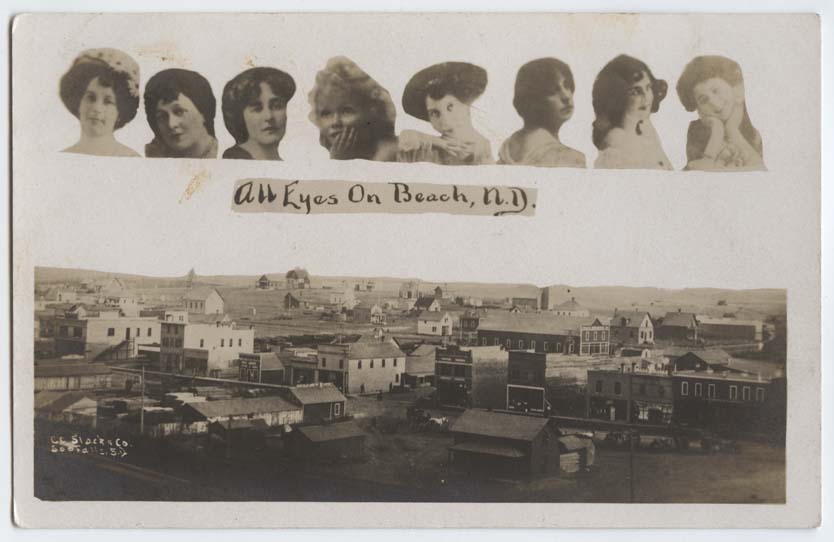

Today, Beach has a population of 981. In 1960, the population was 1,460. Ten years earlier, it had topped out at 1,461. North Dakota has scores of towns with a population of under 1,500 — and falling.

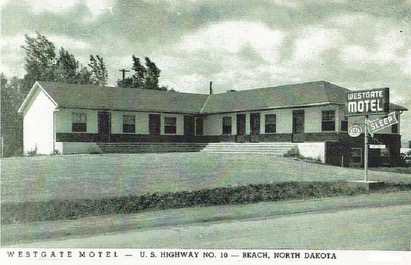

Thanks to the investigative work of a reporter named Bill Steigerwald — often mentioned in my Travels with Charley dispatches — we now know that Steinbeck almost certainly stayed at the Westgate Motel on the main drag of Beach on the night of Columbus Day 1960.

The Westgate is defunct. A local rancher and developer named Mark H. is gutting it inside with the plan to transform it into a 21st-century Airbnb sort of place. He generously permitted me to park my Airstream in the motel parking lot for the night.

Steinbeck wrote a letter to his wife, Elaine, on the little desk in his room. He reported that he had begun the daylong transit of North Dakota on old U.S. Highway 10 at 6 a.m. “I get a little tired, particularly tonight,” he wrote. “The roads were very rough and the wind high.” That certainly sounds like North Dakota!

“I’m staying in a motel called the Dairy Queen,” he wrote. “Reason? The only public telephone in forty miles. The Dairy Queen has a large, beautiful tub and I’m going to get into it almost at once.” Steinbeck may have been confused, or maybe he was making a joke, but there never was a Dairy Queen motel. He was merely identifying the Westgate by way of the Dairy Queen across the street.

Steinbeck wondered out loud in his letter why the town is called Beach. At first glance, it seems like a perfectly absurd name since Beach, North Dakota, is 1,076 miles from the Pacific Ocean, 1,978 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, and 2,172 miles from Hudson Bay. As they say, “There ain’t no beach in Beach.” Steinbeck didn’t have internet access, of course, and although he was aware of the outstanding WPA guides available to individual states, he did not include any of the volumes in his traveling library. Thanks to revolutionary tools that were unavailable in 1960, we can immediately learn that Beach was named for U.S. Army Captain Warren C. Beach, who led a team of railroad surveyors through Dakota Territory in 1880.

Not that you really want to know anything about W.C. Beach — yet another obscure Army officer or railroad engineer for whom a town along the Northern Pacific Railroad was named — but here is a bit. He graduated in the West Point class of 1865. That means that he did not see service during the Civil War. During Reconstruction, he was stationed in a number of places in the former Confederacy: Vicksburg, Mobile, and Galveston. Then, he was transferred to frontier duty, first at Fort Concho, Texas, and later at the Cheyenne Agency (Eagle Butte, South Dakota) in Dakota Territory. He was stationed at Fort Abraham Lincoln (near Bismarck, North Dakota) from 1879 to 1881. During this stint, he captained a railroad survey crew for America’s second transcontinental railroad.

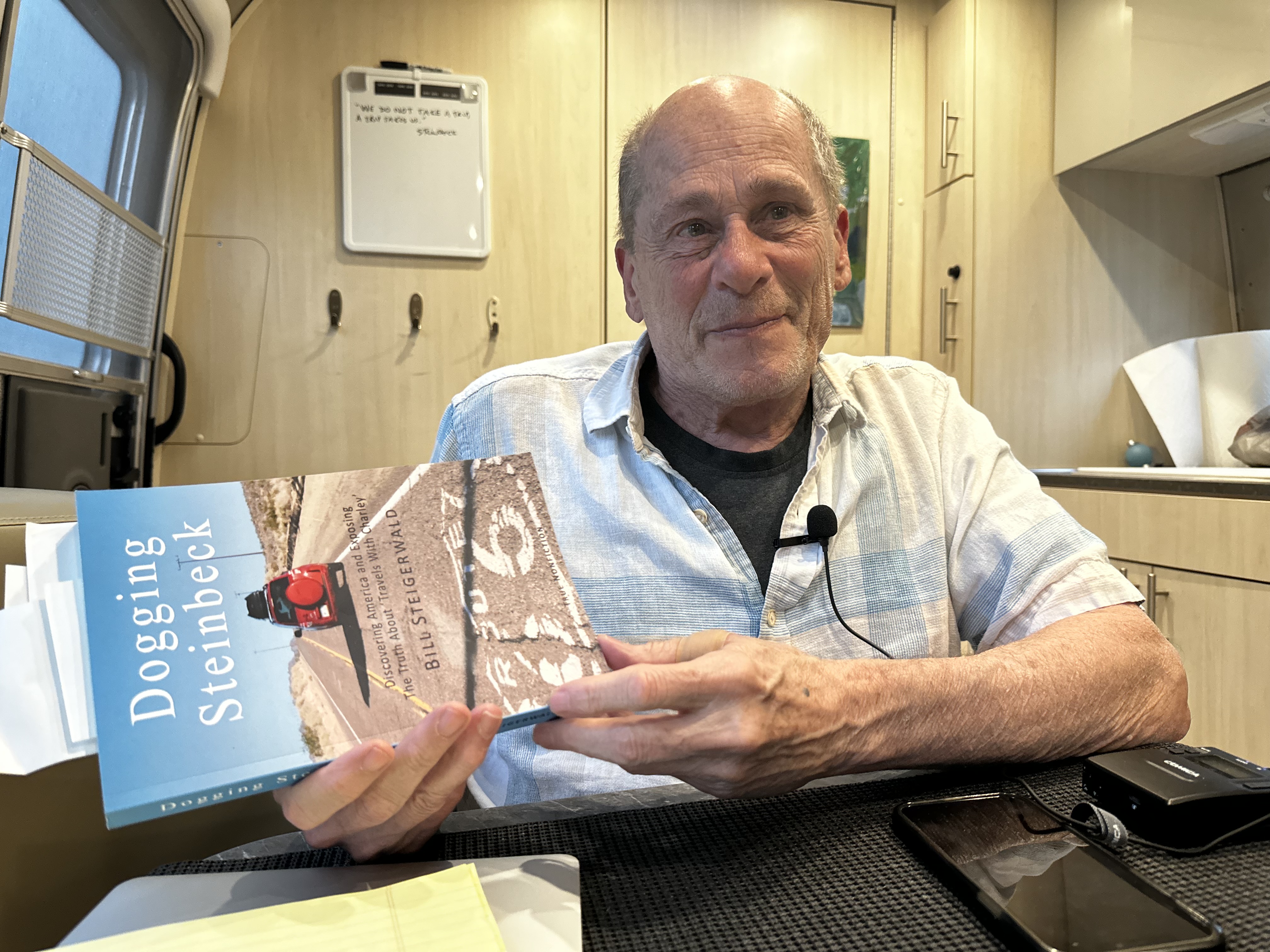

Ode to Bill Steigerwald

Bill Steigerwald retraced Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley journey in real time in 2010, on the 50th anniversary of the Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s 11,500-mile trip. Bill doesn’t like being called a Steinbeck detractor, but that is how he is universally perceived in the “Steinbeck community.” If you title your book, Dogging Steinbeck: Discovering America and Exposing the Truth about “Travels with Charley,” it’s going to be difficult to deny that you are a detractor.

Steigerwald’s investigative discoveries can be summarized in this way. 1. Steinbeck did not sleep in his pickup camper as often as we are led to believe in Travels with Charley. 2. His third wife, Elaine, was with him on the journey more frequently and for longer periods than the book would have us believe. 3. Steinbeck tended to rush from Elaine encounter to Elaine encounter, which meant he had little time to have meaningful encounters with the American people, especially in the West. 4. Some episodes and incidents in Travels with Charley, including some of the most famous, did not occur. 5. Steinbeck was a rich and entitled literary celebrity who loved the good life and was not particularly comfortable roughing it in a truck camper with a chemical toilet. 6. Steinbeck’s New Deal/Great Society Adlai Stevenson and LBJ politics are obnoxious (to Steigerwald, a self-styled libertarian).

I agree with some of this, but I very strongly disagree both with the accusatory (aha! And gotcha!) approach Steigerwald took to his investigations and with the allegation that many of the incidents in the book either didn’t happen at all or not in the way Steinbeck reports them. I believe that almost all of the encounters actually occurred while acknowledging that Steinbeck (like all other writers, including Bill Steigerwald) shaped his experiences when he put them to paper. This is what writers do. Life is almost never as tidy, linear, or straightforward as the stories we tell about life in retrospect.

Put it this way. Travels with Charley is a work of literature based on an actual journey that John Steinbeck took in 1960. Bill Steigerwald naively (in my opinion) wanted to read Travels with Charley as if Steinbeck intended a rigorous book of reportage, as if there were a Charley-cam from which an actual transcript of the conversations could be drawn and a snarky fact-checker should be able to verify that every incident occurred 1) where it is placed in the book and when; 2) precisely as it is narrated in the book; 3) with no embellishments or imaginative reconstruction of dialogue; and that there are no errors of omission or commission. Since Steinbeck didn’t travel with a tape recorder, and he did not have the capacity to memorize every stray conversation on the journey, he inevitably reconstructed those conversations when he wrote the book, and OF COURSE, he brought his enormous gift for storytelling to the enterprise.

Steigerwald and I are now friends. He sat for a two-hour interview in my Airstream way back in Phase One, at Bethany, West Virginia, at a mobile home and RV park that might have been the poster for the Rust Belt. He has mellowed quite a bit in the last decade — his exposé was published in 2014. When I contacted him to set up the interview in his zip code, he invited me to park in his driveway. And he said, “Heck, if you need a hot shower and a comfortable bed, we can provide them.” To which I said, “Hey, wait a minute. You cannot fool me. If I take a shower in your house, you’ll wind up denouncing me for faking the purity of my travels.”

During his journey through North Dakota in October 2010, true to his self-description as an investigative journalist, Steigerwald tracked down the son of the man who built the Westgate Motel in Beach. Doug Davis of Bozeman said his father built the motel, his uncle “designed it,” and his mother managed it. Steigerwald wrote, “His mother had died a few weeks earlier, and he and his older brother found all the motel’s registration books, including those from the fall of 1960, stored at her house — and immediately pitched them in the trash.”

Alas. If those records had been preserved just a few more weeks, Steigerwald might have been able to determine a: whether Steinbeck registered at the Westgate on or about October 12, 1960, and b: what room he stayed in. It is possible, of course, in that more innocent era, that Steinbeck, who insisted that he traveled America incognito in 1960, registered under an alias. Now, if Steigerwald were really a top investigative journalist, he would have found the landfill in question and excavated those registration records. The Search for Truth has its limits.

I had dinner in Beach with old friends and new. We agreed that making more of Steinbeck’s visit would be an asset to the community. We talked about the plight of small towns in rural America. We group-gushed at how much we love the plains, the buttes, and the badlands of North Dakota.

Steinbeck did not keep a journal during his 1960 trek. He wrote several letters to his wife Elaine back in New York and called her once or twice a week from somewhere on the road. He was dependent, of course, on the telephone infrastructure of his times. It was on one of those calls that his book got its title. Elaine was listening to his account of his misadventures with the poodle Charley. Suddenly, she said, your adventures remind me of Robert Louis Stevenson’s book Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. Steinbeck immediately said, that’s it, that’s my title. You have given me the title for the book. This was not the first time a Steinbeck spouse gave him a world-class title. His first wife, Carol Steinbeck, suggested the title The Grapes of Wrath for his greatest book. It’s hard now to think of the novel by any other name.

Every Steinbeck scholar studies his countless letters with great care. He was a voluminous letter writer, and he often used his morning letters as a warm-up ritual to process the artistic ideas he was struggling with and to tune up his prose. The Travels with Charley letters are essential background reading for anyone trying to make sense of the 1960 journey. It’s hard to think of any American writer whose letters are as essential to understanding their work as are those of Steinbeck. Lovers of his last big novel East of Eden, know that the letters he wrote most mornings to his longtime publisher and intimate friend Pascal Covici were published posthumously as Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters, which themselves represent an American classic.

In the letter from Beach to Elaine, Steinbeck reveals several details that never found their way into Travels with Charley. The book (published in 1962, written in NYC and Barbados) does not mention a motel and leaves the reader believing that he spent the night in the badlands in his truck camper. Not so. Score one for Steigerwald! He needed a telephone. He wanted a bath. “The Dairy Queen [motel] has a large, beautiful tub, and I’m going to get into it almost at once.” Steinbeck loved his baths

In the letter, he writes what amounts to the first draft of one of the most famous passages in Travels with Charley, the one in which he says that it is the Missouri River at Bismarck and Mandan, North Dakota, where the map should fold. Here’s the passage from Steinbeck’s letter:

“North Dakota is like the great plains anywhere, and then — Wham! The Missouri River instantly becomes the West, brown hills, and then the moon country of the Badlands.”

In the book, this becomes:

“Someone must have told me about the Missouri River at Bismarck, North Dakota, or I must have read about it. In either case, I hadn’t paid attention. I came on it in amazement. Here is where the maps should fold. Here is the boundary between east and west. On the Bismarck side it is eastern landscape, eastern grass, with the look and smell of eastern America. Across the Missouri on the Mandan side, it is pure west, with brown grass and water scorings and small outcrops. The two sides of the river might well be a thousand miles apart.”

Reread the passage from the letter to Elaine and then the finished product in Travels with Charley. You immediately get a glimpse into the creative process, how a brief observation in an informal letter becomes — months later — an example of literary genius. This creative transformation may be seen as a metaphor for the entire literary gestation of Travels with Charley.

In the letter to Elaine, he provides additional details about his impressions of North Dakota, particularly the badlands. The West country features “what you call painted canyons [he drove past Painted Canyon Scenic Overlook on Highway 10] all blue and red. It was rainy at first and then the sun burst out and whopped it up. Charley has had his dinner now and peed on a rock and is sitting there watching me with a look of amused satisfaction on his face.” I’ve read this letter dozens of times over the years, and yet this is the first time I noticed the rain.

Steinbeck announces that after his luxurious bath, he will “then wash shirts and sox.” In the tub, one guesses.

And he says that he ventured a block or two to one of the taverns of Beach but “there was nothing talked but deer hunting. I’ve seen about six go by on car fenders today.” October was deer hunting season — and Dakotans, then and now, take the short deer hunting season very, very seriously. Now the detract. … I mean the investigative journalist Steigerwald did not pin down which bar Steinbeck visited on Columbus Day evening, perhaps because one of the few enterprises small towns have in multiples are bars — and churches. There are, for example, even now two Lutheran churches in Beach. And to his great credit, Steigerwald is one of the only Steinbeck re-tracers who does not obsess about food and IPA beers.

The other night, I was able to tour the inside of the Westgate Motel’s shell. Most of the interior walls have been knocked down, but there are still four old bathtubs right where they sat in Steinbeck’s time. I reckoned that the laws of probability favored at least one of those tubs in which Steinbeck soaked his weary body. The tubs were pretty short, and Steinbeck was pretty tall (6 feet even). I got in one fully clothed as part of my pilgrimage but did not lie down.

It was a wonderful stop on the Steinbeck Trail. I can attest (I would swear) that I have not fabricated any person, event, place, or encounter from my 20 hours in Beach. There are considerable omissions, of course, the kind that bring down the wrath of the Steigerwaldians. I walked across the street to buy a sponge at the Dollar General store; in some quarters, that is rural town sin. At dinner, I ordered the San Francisco Sourdough patty melt, but I did not eat all of it. I had a glass of pinot grigio (or, in Beach’s nomenclature, White) with dinner. Some local ruffians fired off bottle rockets, Roman candles, and firecrackers in the middle of the night at close range to my Airstream. I took delivery of an exquisite ceramic bowl from Beach’s superb potter Tama Smith, an old dear friend, the kind of North Dakotan we could use a lot more of. I did not pee in the Badlands.

I hope these additional details satisfy my friend Bill. If he finds out later it was Merlot (i.e., Red), he’ll go after me like a badger.

Let me make the following statement for the record. I said these words to Steigerwald in the Airstream in Bethany, West Virginia, and he very nearly blushed. “No future Steinbeck scholar working on Travels with Charley will be able to avoid coming to terms with Dogging Steinbeck.” Steigerwald did absolutely important legwork during his 2010 re-enactment (that nobody had bothered previously to do), and the facts he ascertained from excellent and dogged research change the way we see the man, the novelist, the husband, the great book he wrote about it.

The next hotel I know Steinbeck stayed in is not until San Francisco, and our Listening to America budget will not permit an honorary stay even for a night. So, one takes the identifiable Steinbeck hotels/motels one gets.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.