Clay visits Northern Maine on the trail of John Steinbeck’s visit with French Canadian potato harvesters, detailed in Travels With Charley.

In my second week of travels, I drove up much of the length of Maine, because in 1960 John Steinbeck was determined to touch the roof of the United States before turning west, and I reckoned you aren’t really fulfilling the mission unless you follow his path.

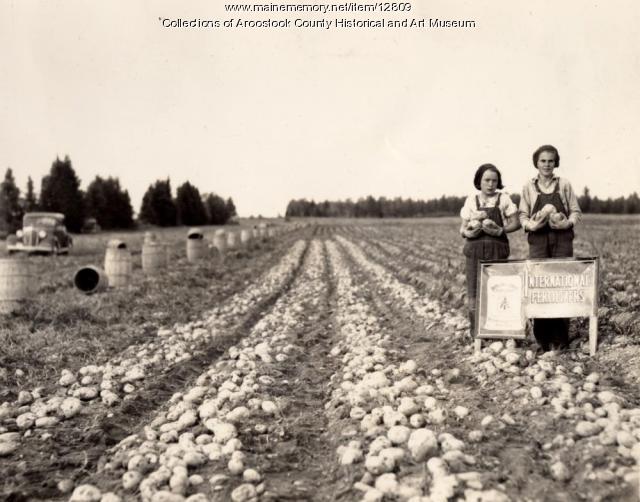

When I was in central and northern Maine, I asked about “Canucks” or, more specifically, French Canadian potato harvesters. Everyone I met said you have to go all the way up to Fort Kent to have any chance to meet such people, and maybe not even then. When Steinbeck came through, Maine still ranked first in American potato production and automation had not yet eliminated the need for human laborers.

Maine is no longer the great potato producer it once was. Today, it ranks eighth after Minnesota, Colorado, North Dakota, Oregon, Wisconsin, Washington, and Idaho.

We don’t use the word “Canuck” anymore. Various dictionaries label it as “sometimes offensive,” “often derogatory,” or”considered by some insensitive.” It can refer to all Canadians but is more often used by eastern Canadians or French Canadians.

John Steinbeck had a chance encounter with a family of French Canadian potato harvesters during the first week of his transcontinental journey in 1960. He called them Canucks with no sense that the term might be regarded as unflattering.

At the end of a day of travel, Steinbeck parked his rig on the edge of what he called a lovely lake about 95 yards from a cluster of tents and trucks where the agricultural laborers spent their nights. He did a little lakeside laundry. When he smelled the odor of soup wafting in from their camp, he wrote, “I found myself thinking, ‘What charming people, what flair, how beautiful they are. How I wish I knew them.’ And all based on the delicious smell of soup.”

Steinbeck decided to make contact with them. As usual, he sent his French poodle Charley out as his ambassador, waited a few minutes, and then wandered over to reclaim the dog and apologize for any trouble he may have caused. The party consisted of three giggling girls, the family chieftain in the prime of his life, three wives, one pregnant, the elderly patriarch of the family, two brothers-in-law, and “a couple of young men who were working toward being brothers-in-law.” Plus, an unspecified number of children.

After some small talk about Charley’s birthplace in France, during which the French Canadians praised Rocinante (what they called his “roulotte”), Steinbeck invited them to stop by later to look at his rig.

The great novelist bustled about preparing his camper cabin for guests.

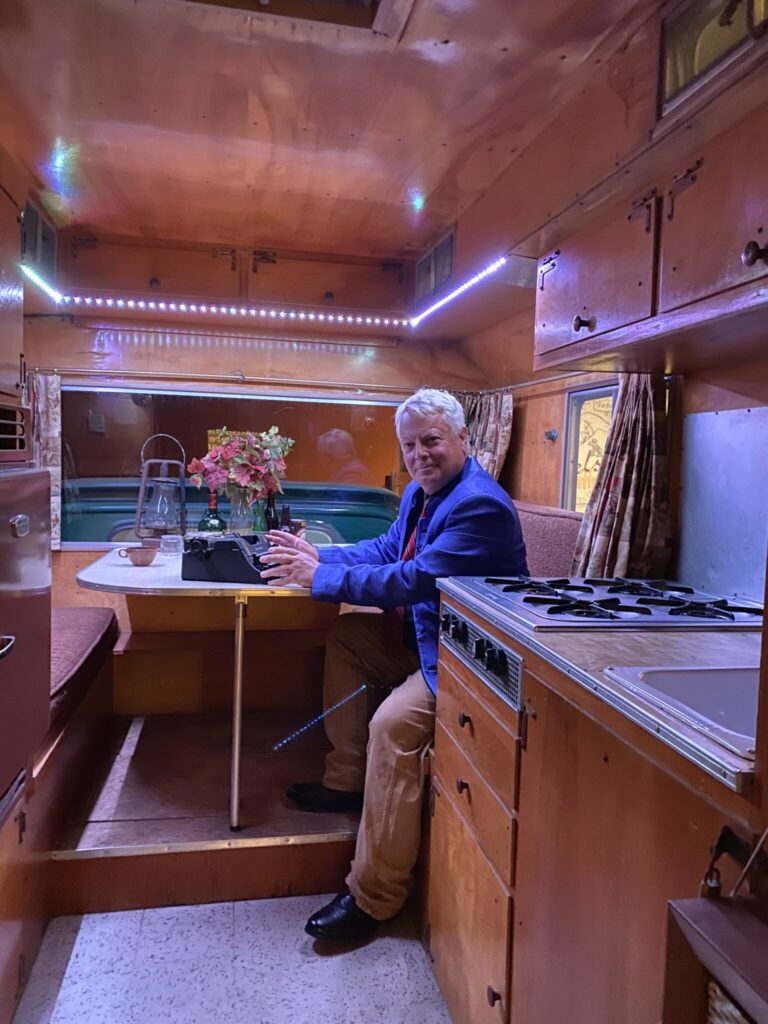

The French Canadian family (never named) stopped by in the evening. Steinbeck invited them into the “cabin” and urged them to sit around his dinette table. I’ve been in Steinbeck’s camper (at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California), and I can confidently declare that it must have been a tight fit. Here’s how he puts it: “Six people can squeeze in behind my table, and they did. Two others beside me stood up, and the back door was wreathed with children’s faces.” Counting the host, that puts nine adults in the little cabin, 10 if you include Charley, who was a very large dog.

Steinbeck served the adults beer.

He wrote, “After the [previous] night of desolate loneliness, I felt very good to be surrounded by warm and friendly but cautious people. I tapped an artesian well of good feeling and made a small speech in my pidgin type of French.”

In the conversation that followed, the family told their story in that congested cabin. They were migrant laborers. They crossed the border from Canada every year to harvest potatoes in Maine. The border authorities of both nations were friendly, understanding, and cooperative. Their transnational transits and paperwork were handled by a professional agent who took a small percentage of their pay for his services. Steinbeck, who knew something about seasonal laborers, wrote that wherever he had met migrant workers in America, “there has always been a contractor in the background to smooth the way.”

The family had a small farm in Quebec. Each year, they “came over the line to make a small nest egg. They even carried a little feeling of holiday with them.” All of the adults worked in the fields, and the children helped to the extent that they were able.

After a decent interval, when everyone had relaxed and the atmosphere seemed right, Steinbeck reached into a storage bin and produced a bottle of fine cognac. The “chieftain” John, who managed the family’s day-to-day affairs, passed the bottle to the patriarch, “and the old man smiled so sweetly that for the first time I could see that he lacked front teeth.”

Steinbeck poured. When his guests tasted the “particulier du Departement de Charente,” the cabin hummed with non-verbal sounds of pleasure all around. “The cognac was very, very good,” Steinbeck reported, “and from the first muttered ‘Sante’ and their first clicking up you could feel the Brotherhood of Man growing until it filled Rocinante full — and the sisterhood also.”

His guests predictably and properly refused seconds, but they quickly yielded and let Steinbeck refill their cups. Then Steinbeck wrote one of the best lines in Travels with Charley: “And the division of thirds was put on the basis that there wasn’t enough to save.” Occasional lines like this one make Travels with Charley such an endearing book.

Steinbeck realized he was experiencing a moment of magic in a far corner of the United States.

“And with the few divided drops of that third there came into Rocinante a triumphant human magic that can bless a home, or a truck for that matter — nine people gathered in complete silence and the nine parts making a whole as surely as my arms and legs are part of me, separate and inseparable. Rocinante took on a glow it never quite lost.”

A glow it never quite lost.

Shortly thereafter, the patriarch motioned everyone out of the camper: “Such a fabric cannot be prolonged and should not be. … They went into the night, their way home lighted by the chieftain John carrying a tin kerosine lantern. They walked in silence among sleepy stumbling children and I never saw them again.”

He never saw them again.

Verisimilitude

Travels with Charley recounts about a dozen major (and many more minor) encounters between Steinbeck and the people he met along his 11,500-mile journey in 1960. The first of the major encounters was with the Canuck family in northern Maine.

Virtually all Steinbeck scholars now agree that there are some fictional elements in Travels with Charley. At the very least, there is now a consensus that some of the dialogue in the book was embellished as he wrote up his journey in retrospect, months after his return to New York. It is possible, too, that there are a few composite characters in the book. It is even possible that Steinbeck invented parts of or all of a few of the encounters. I doubt this, but it is possible. One end of the spectrum of critical opinion is occupied by the investigative journalist Bill Steigerwald, a determined and militant skeptic who gives credence to few, if any, of Steinbeck’s road encounters. The other end of the spectrum is represented by Steinbeck scholars like San Jose’s Susan Shillinglaw, who is, of course, aware that Travels with Charley is what is known as autofiction but who believes that there is substantial authenticity in the bulk of Steinbeck’s encounters.

At this point, every Steinbeck scholar (and readers interested in this exercise) must decide where they land on the spectrum. My view, which comes after repeated readings and rereadings of Travels with Charley, several close readings of Steigerwald’s Dogging Steinbeck, Jackson Benson’s relevant chapters in his massive 1980 biography of Steinbeck, the outstanding literary criticism of Steinbeck scholar Robert DeMott and biographer Jay Parini, and my own long, careful interviews with Steigerwald, DeMott, and Parini, all conducted on this national Steinbeck journey, is that the great majority of the encounters in Travels with Charley actually occurred, in much the way Steinbeck remembered them. That there is embellishment is undeniable. Travels with Charley is a work of literature, not objective reportage. As Steinbeck notes several times in the book, storytellers inevitably shape their experiences to give them coherence and narrative bite. That some encounters might have occurred elsewhere than reported in the book is quite possible. That several minor encounters and conversations picked up along the way may have been melded during the writing process into composite characters — consciously or unconsciously — is certainly possible. But I doubt Steinbeck invented anything in the book out of whole cloth.

I may be wrong. One of the fruits of a long, obsessive adventure like this, indeed one of the purposes of my journey, is to feel my way through his 1960 journey as it was reported in the book he published 18 months later; to let my journey enlighten my understanding of his. My mind is open.

The probability that the Canuck incident never occurred at all approaches zero. That it happened in precisely the way Steinbeck writes about it is unlikely. But I believe it happened, and here’s why:

- The encounter came early in the mission when Steinbeck’s energy and exploratory spirit were still high. He went on his journey to reconnect with the peoples of America, and at the top of Maine, he did so.

- The incident seems to have carried Steinbeck back to the mid-1930s when he traveled the Central Valley of California in his “pie wagon,” a panel truck formerly used to deliver bakery goods, to study the plight of the displaced Okies, and to provide help where possible. Here, at the other end of the country, was an economically marginal itinerant family, toiling together to eke out some modest prosperity away from their home across the border, and here — in his new pie wagon — was the American novelist who achieved his fame writing about a family in a similar, albeit more desperate, situation. These were, in a sense, French Canadian Joads. In a number of the episodes of Travels with Charley, Steinbeck seems to be hearkening back to themes of his earlier books. In some respects, Travels with Charley is a kind of summing up.

- Steinbeck tells us at the beginning of his book that he stocked up on a fairly serious volume and variety of alcohol precisely to be in a position to host parties in Rocinante. Here in potato country, it was his first real opportunity. One of his goals was to entice some of the people he met into his little aluminum den, hear their stories, and show them genuine hospitality. The success of his early Canuck and cognac party boded well for the transcontinental quest he had undertaken. Unfortunately, there would not be many such intimate evenings in Rocinante, but he had started the trip successfully.

- As usual, “the genius is in the details.” Because he did not have enough glassware to host so large a group, Steinbeck cobbled together “three plastic coffee cups, a jelly glass, a shaving mug, and several wide-mouthed pill bottles,” from which he “emptied their capsules into a saucepan and rinsed out the odor of wheat germ with water from the tap.” He made coasters out of “folded paper towels.” He had “picked a bouquet of autumn leaves and put them in a milk bottle on the table.” I ask of the Travels with Charley skeptics: how likely is it that Steinbeck made these particulars up? After he “set my cabin in order,” and fussed over all of these preparations, Steinbeck wrote,”It’s amazing what trouble you will go to for a party.” As far as I am concerned, this has the ring of truth and authenticity.

- Why would Steinbeck make this incident up? I ask this question of each of the major encounters in Travels with Charley: the Canucks, the Canadian border officer, the couples in the mobile homes, the itinerant Shakespearean actor in eastern North Dakota, the taciturn and the voluble ranch denizens of the North Dakota badlands, the closeted young gay man in Idaho, the four men he questioned about Civil Rights in the Deep South? What does Steinbeck gain by inventing this encounter with French Canadian harvest gypsies? What convincing argument can be made that he invented an encounter with potato pickers?

- Retracing Steinbeck’s journey in 2010, my friend Steigerwald became so disillusioned when he discovered that not everything in Travels with Charley happened as if recorded by a “Rocinante cam,” that he determined to prove that the whole thing was a sham and Steinbeck a fraud. Of this famous incident, he writes: “The extended family of Canucks jamming into Rocinante is a favorite scene in Charley. But like other favorite scenes in the book, it most likely never happened — certainly not in the protracted, theatrical way Steinbeck described. … My guess is [that this incident happened] only in his novelist’s imagination.” Later, Steigerwald concludes, “The more I learned about Steinbeck’s journey, the more obvious it was becoming that nothing in it could be believed.”

- Above all, Steinbeck was deeply moved by his evening with the shy potato harvesters, which had an innocence that carried him back to the most intense period of his creative life. The following morning, “I made a little sign on cardboard and stuck it in the neck of the empty brandy bottle, then passing the sleeping camp I stopped and stood the bottle where they would see it.” He drove away “as quietly as I could.” And he concludes the episode with two sentences that essentially guarantee the authenticity of the encounter: “There are times that one treasures for all one’s life, and such times are burned clearly and sharply on the material of total recall. I felt very fortunate that morning.” There is, I believe, no snarky answer to this.

Unfortunately, I had no such encounter with a French Canadian family in northern Maine. At any rate, it would have been impossible to replicate the magic. The agricultural and petrochemical industrial complex manufactures today’s potato harvester. And we are no longer a people much open to innocence.

I asked my friend, Nate Calderone of Salida, Colorado, to make one of his delightful and spirited illustrations in honor of the Canuck incident. (See top of story.) I find his work whimsical and deeply satisfying. I hope you enjoy his art as much as I do.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.