Some thoughts on the J. Robert Oppenheimer film. First, I predict that Robert Downey, Jr. will win the Academy Award for best supporting actor. It is a stunning performance as Lewis Strauss, the nemesis of Oppenheimer. The film will win half a dozen Oscars at minimum, including perhaps best supporting actress for Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer.

I got home from a Listening to America trip to the Black Hills and the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation on the evening of Thursday, July 20. I was scheduled to see the movie with friends on Sunday. But when I woke up Friday morning, I realized I couldn’t wait. The first showing in Bismarck, N.D., was at noon Friday. I got to the metroplex at 11:35. The doors were still locked! Fifteen or so people stood around waiting for the theater to open. The local TV station was there, but they only wanted to talk with people who were there to see Barbie.

I bought the first ticket for Oppenheimer in Bismarck. I was the first in the theater. I chose the ideal seat.

In my strange career, I have portrayed perhaps a dozen different historical characters. Because I was the director of the Great Basin Chautauqua in Reno, Nev., I had to select themes and take on characters to fit those themes. One year we did World War II characters. I chose Oppenheimer.

Why? My background in physics was merely (pathetically) Physics for Poets in my first year of college. But I had somewhere read that when the test bomb went off, Oppenheimer said, quoting the Bhagavad Gita, “I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.” This is precisely why I chose to portray him in Chautauqua. Someone who could say that, could quote that, whose mind worked like that, who had that soul — I wanted to try to understand. So, I studied Oppenheimer. The first book I read was Peter Goodchild’s J. Robert Oppenheimer: Shatterer of Worlds. And then many more. Eventually the splendid American Prometheus. I still have the notes I wrote in reading Goodchild’s book, much of it one day in Arles, France, where I was leading a cultural tour about Jefferson there.

As I got to know Oppenheimer — a complicated genius — I learned for the first time that he had been destroyed by the military industrial complex because he was insufficiently supportive of the American quest to build a hydrogen fusion device. He believed that an H-bomb could only be seen as a weapon of mass destruction. I learned of the security clearance hearing in the spring of 1954. The learning curve was straight up.

I even attempted to learn something about quantum mechanics. I read four or five books, including the Tao of Physics and some more serious accounts, but every time I thought I was just about to understand, my mind fell back into Newtonian ruts. I was a little relieved when I read that Niels Bohr (the greatest of quantum physicists) had said, “If anybody says he can think about quantum problems without getting giddy, that only shows he has not understood the first thing about them.” I was awash in Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, Schrödinger’s Cat, one atom at one end of the universe tickling another faster than the speed of light. …

It wasn’t until I realized that Oppenheimer was a tragic figure that I fell in love with him. Aristotle’s formulation is that a tragic figure is a great man (or woman) who winds up being complicit in his fall. As Hamlet puts it:

So oft it chances in particular men

Hamlet, William Shakespeare

That for some vicious mole of nature in them

As in their birth (wherein they are not guilty

Since nature cannot choose his origin),

By the o’ergrowth of some complexion

Oft breaking down the pales and forts of reason

Or by some habit that too much o’erleavens

The form of plausive manners — that these men

Carrying I say, the stamp of one defect

Being nature’s livery or fortune’s star

Their virtues else (be they as pure as grace,

As infinite as man may undergo)

Shall in the general censure take corruption

From that particular fault.

Oppenheimer contributed to his fall. He was arrogant. He did not suffer fools and by his intellectual standards, most people were fools. He treated others to what someone called his Blue Glare Treatment. He arrogated to himself the right to determine what constituted a security breach. He spent the night with an old girlfriend during the project while he was married and she was a communist party member. He mishandled the notorious Chevalier Incident. From a certain point of view, he was security nightmare.

Hubris. Oppenheimer had hubris. When his enemies decided to destroy him, they found that he had handed them the hammer.

As a humanities scholar, I am drawn to individuals who have a fissure at the center of their being: Jefferson (race and slavery), Meriwether Lewis (who could not reenter civilized life), Steinbeck (who fundamentally believed he was mediocre), John Donne (worldly Jack Donne, otherworldly John Donne the divine), Hamlet (what a piece of work is a man, and yet what to me is this quintessence of dust?), and Oppenheimer, who could not reconcile his capacity to build a weapon of mass destruction with the ethical consciousness he had assiduously developed over a lifetime of hard reading. I’m fascinated by the divided self. I suppose I have taken on historical characters because I have a divided self. Not that we all don’t, but most people find ways to live in cheerful denial, except when they are drunk, terminally exhausted, or over the line of acceptable human conduct. I seek out the fractured.

But if we accept that Oppenheimer had significant faults, and that he contributed to his demise, the truth emerged in my research that he was victimized by some of the worst dynamics of American life: intolerance for eccentricity, intolerance for views that are not squarely within the establishment’s worldview, demonization of irony and nuance, distrust of intellectuals, anti-intellectual smugness, fear of the cosmopolitan. … This is the spirit of Joseph McCarthy, Richard Nixon, Barry Goldwater, Sean Hannity, and countless others not worth naming in an historical essay. The American Cold War establishment destroyed Robert Oppenheimer because they wanted to live in a Manichaean world of black and white, good and evil, simpleton “values,” heroes and demons. They destroyed him because he was a fully evolved human being with a rich and delicious moral and ethical consciousness, and they wanted merely to call the Soviet Union an evil empire. So, too, when John F. Kennedy gave his fabulous peace speech at American University on June 10, 1963, wherein he said that the Russians were people just like us and though we disagreed profoundly with their political and economic system, we need to realize that they love their children just as we do, that there is more we have in common than that which divides us and we must learn to share the world — as soon as he said those words, the bullets were finding their way into rifles on the streets of Dallas. Because we could not tolerate such a man in a position of power.

David Lilienthal said of Oppenheimer, “It is worth living a lifetime just to know that mankind has been able to produce such a being.” Although I love Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis and take great joy in Theodore Roosevelt, Oppenheimer is the role of a lifetime. He’s my favorite character. This startles some people, but if you know my fatal attraction to unresolved human great ones, it makes perfect sense.

I sat in the theater Friday for three hours, and though at some point I had to pee, I would not let myself leave even for four minutes. I was mesmerized. The film is historically accurate. In fact, it precisely quotes some of the most important utterances of Oppenheimer and everyone around him. There is no significant historical problem in the film. I will review it here as soon as I finish this personal account of my experience, but what I expected — that I would be shaking my fist at the screen, outraged over Hollywood’s inability to let a story stand — never happened, not even slenderly.

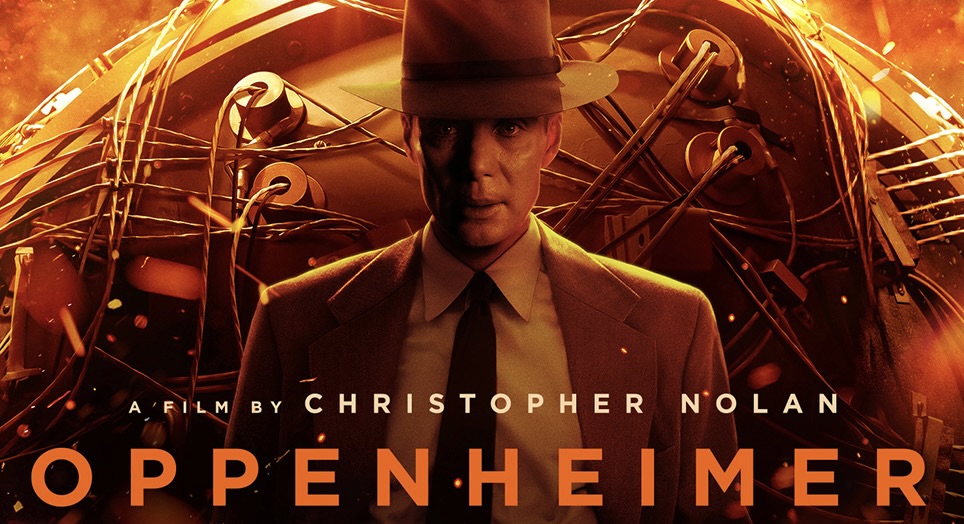

Oppenheimer is one of the best movies I have ever seen. I had expected to feel peevish about Cillian Murphy because I am J. Robert Oppenheimer, but of course that was ridiculous. He nailed it. His existential loneliness. The downcast eyes. The embrace of martyrdom. The unresolvable paradox of his agency in killing 200,000 people and his revulsion at what he had unleashed.

I have a strange personal connection with Oppenheimer, along the lines of the first chapters of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, that what is going on in the minds of your parents when they conceived you is significant. My father was a brilliant liberal alcoholic, a young man when Oppenheimer was rejected and shamed. My father was something of a Kerouacian in the years just after the war. He had served in the Army at White Sands when Wernher von Braun was there. He saw missiles rocket out of White Sands. I know he would have been appalled by the government’s treatment of Oppenheimer and even living in a small North Dakota town he would have been riveted by the security hearings, outraged by the verdict. He might have tried to talk to my mother about these things, but back then, at least, she would not have done more than listen without fully comprehending what was at stake. I mean no criticism of my mother. She was a Minnesota farm girl then raising her first child. On the night they conceived me, Oppenheimer was in the Inferno of the Cold War in America. I was born with my father deeply concerned about America. Just saying …

I would love to tour the country performing Oppenheimer. I have several performances lined up. Last night I ordered a new 1940s gray suit. My porkpie hat is ready on the shelf in my closet. I have my slide rule handy. I have my father’s pipe. I’m re-reading the two finest books about Oppenheimer: American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, and Mark Wolverton’s A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

I burst into tears two and a half times in the film. First, when Oppenheimer names the test site Trinity after a sonnet by my favorite poet John Donne, “Batter My Heart Three-Person’d God.” Why? Because of my lost youth. I remembered the young man I was when I first came away from Oxford University — the world was all before me — and I grieved the loss of that promising young scholar. Second, when Oppenheimer (C. Murphy) was all alone in the cosmos while his Los Alamos colleagues danced and cheered orgiastically at the success of the bomb. And third, the half-choked moment, when Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer unleashed her fury on the government’s prosecutor Roger Robb near the end of the film. (Robb is mischaracterized by Jason Clark.)

This morning, I pulled the Sermons of John Donne off my Renaissance literature shelf — after an interminable, inexcusable absence.