“I am in love with Montana. For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection, but with Montana it is love.” John Steinbeck

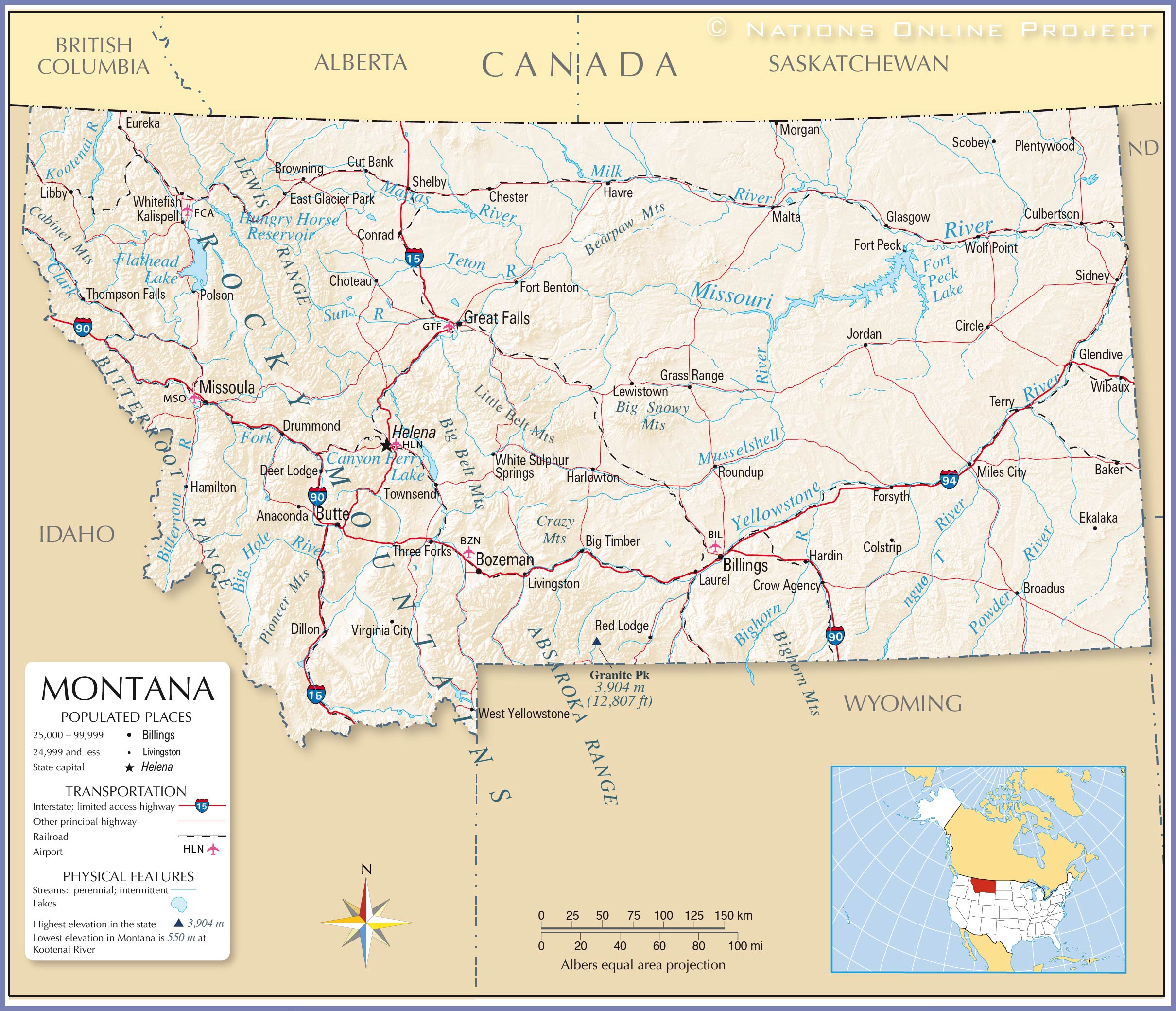

John Steinbeck loved Montana — actually, he fell in love with it. So far as we know, he had never been there before 1960. His travels across the country had all been at lower latitudes. On October 13, 1960, he crossed the North Dakota state line west of Beach and drove through Montana on old U.S. Highway 10 for the next couple of days.

As he left North Dakota, he wrote, “The next passage in my journey is a love affair. I am in love with Montana. For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection, but with Montana it is love, and it’s difficult to analyze love when you’re in it.”

Steinbeck only diverted from U.S. 10 twice in colossal Montana, the fourth largest state: first, to visit the Little Bighorn Battlefield, which merits only one short paragraph of 74 words in Travels with Charley; second, to visit Yellowstone National Park, which proved abortive when his French poodle Charley went berserk at his first encounter with Yellowstone’s bears.

We know Steinbeck spent one night at an “auto court” near Livingston and a second night camping somewhere northwest of Missoula, near Superior, Montana. As he rolled through the state, he bought a Stetson cowboy hat in Billings, a jacket (it was autumn) in Livingston, and a Remington bolt-action .222 rifle (with scope) in Butte.

U.S. Highway 10 is mostly gone now, either subsumed under I-94 and I-90 or demoted to frontage road status. In retracing Steinbeck’s 1960 journey, I spent as much time on Old U.S. 10 as possible. Each time I found a patch of U.S. 10, a wave of romance and nostalgia percolated through me. I’m old enough to have grown up when the interstate highway system was only in its adolescence out West. I remember the old asphalt two-lane highway as a thrilling roller coaster journey between Glendive and Miles City.

Steinbeck said he would perhaps choose to live in Montana, if only there were an ocean nearby. “Montana has a spell on me. It is grandeur and warmth. If Montana had a seacoast or if I could live away from the sea, I would instantly move there and petition for admission. Of all the states it is my favorite and my love.”

If There Were Only One State

If he had been younger and in better health, he possibly would have purchased property in Montana, which has become a writer’s (and celebrity) paradise. Tim Cahill, Thomas McGuane, Rick Bass, Jim Harrison, Ivan Doig, James Welch, William Kittredge, and Annick Smith are (or were) all Montana authors. Livingston and Missoula (home of the University of Montana) are regarded as the state’s writers’ communities.

I’m a proud North Dakotan and one of the state’s leading cheerleaders, but like Steinbeck, I have a confession to make. Not only do I love Montana more than any other state (and that includes Colorado, California, Utah, and Wyoming), but when people ask me about my love of the West, I invariably say, “If there were only one state, it would have to be Montana.”

The U.S. 10, I-94 and I-90 Northern Pacific Railroad corridor that Steinbeck drove is very beautiful, particularly those stretches that follow the course of the Yellowstone River. America’s interstates are routinely abused for being boring, preferring efficiency over beauty, and piercing America through its least scenic landscapes. This is not always true — not on I-70 between Vail and Grand Junction, including the stunning highway terracing through the Colorado River’s Glenwood Canyon gorge. And no reasonable person could find fault with I-94 and I-90 through much of Montana.

The drive from Glendive, Montana, to Three Forks ranks high on my list of top 10 American highways. I’ve seen the Yellowstone — regarded as the longest undammed river in the U.S. — in all of its moods, and they are all beautiful to behold. But my favorite season in the Yellowstone Valley is October, when the river is low and almost incredibly blue, and the cottonwood trees have turned to the most vibrant yellow-gold you could imagine. Off in the distance, you see ridges, bluffs, buttes, and then, as you move west of Billings, the lesser mountain ranges of Montana, all beckoning, all urging you to slow down, turn off the freeway, and explore.

If Steinbeck had had more time, he could have seen parts of Montana that are even more beautiful than the corridor he drove on cool (even chilly) fall days in his pickup camper Rocinante. I could spend the rest of this weekend writing joyously about dozens, even scores, of Montana highways you’d want to travel if you had the opportunity.

Sometimes, when I travel from North Dakota to Missoula (and beyond), I drive U.S. 12, once regarded as “the shortest route from Minneapolis to Yellowstone National Park.” I generally pick up U.S. 12 at Miles City and drive along the Musselshell River to White Sulphur Springs, then to Helena and beyond. The Musselshell River is more modest, isolated, and closer to the highway than the Yellowstone. As William Least Heat Moon argued in Blue Highways, one of the benefits of the interstate highway system is that it draws most of the commercial traffic away from the rest of America’s roads, particularly interstate truck traffic, and frees up those secondary and tertiary roads for those who are not in a hurry.

Another superb drive is Montana 200, which you can take all the way from Sidney on the North Dakota border to Thompson Falls, out near Idaho. I just drove it from Missoula to Great Falls (165 miles) on a perfect July evening. Although I needed to get to Great Falls before dark, I stopped a dozen times to get out and stand by the side of the road, taking photographs that cannot possibly do justice to the vast magnificence of the landscape. One of the additional benefits of driving that stretch of Montana 200 is that you pass through the lovely hamlet of Lincoln (population 1,005), which was the home of the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. His cabin used to be on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. Now, it can be seen in the museum at the FBI headquarters in Washington. Kaczynski lived in the mountains near Lincoln for 25 years, sent out 16 bombs, killed three people and injured several dozen others. He died in the Federal Medical Center at Butner, North Carolina, in 2023. He was 81.

Highway 200 from Circle, Montana, to Lewistown belongs on any shortlist of the loneliest highways in America. You come to the top of a hill and look down at the narrow ribbon of highway stretching to the far horizon through essentially unpopulated country. It takes your breath away, and you understandably ponder what it would mean to break down on that highway, out of cell range and as far from a AAA rescue as you can imagine. And when you finally reach the next ridgeline 10, 20, or 40 miles farther west, you look down on another endless thread of highway, and then another, and another. Every time I drive that road, I fall in love with America all over again. I invariably stop a dozen or more times on that 195-mile stretch to take photographs and thank my lucky stars that I live in the American West when it is still possible to drive your own vehicle at your own pace and for your own purposes through endless plains country. I have an artist friend in Duluth, Minnesota, who paints giant murals of America’s grasslands, sometimes dozens of feet wide. Her name is Catherine Meier. I always text her a photograph of the starkest, most beautiful landscapes, and I can almost hear her sigh all the way from Duluth at the artistic possibilities. You can see her work at catherinemeier.com.

Steinbeck spent a statistically minimal amount of time at the Custer battlefield in 1960. If he had had “world enough and time” and the inclination, he might have visited several other important hot spots of the 50-year conflict between white and Native Americans in Montana. He might have ventured to the site of the Marias Massacre near Shelby, where, on January 23, 1870, troops of the U.S. Second Cavalry massacred 173 (some say 200) Piegan Blackfeet men, women, and children, many of whom were suffering from smallpox. Reason? Border depredations carried out by the Native resistance.

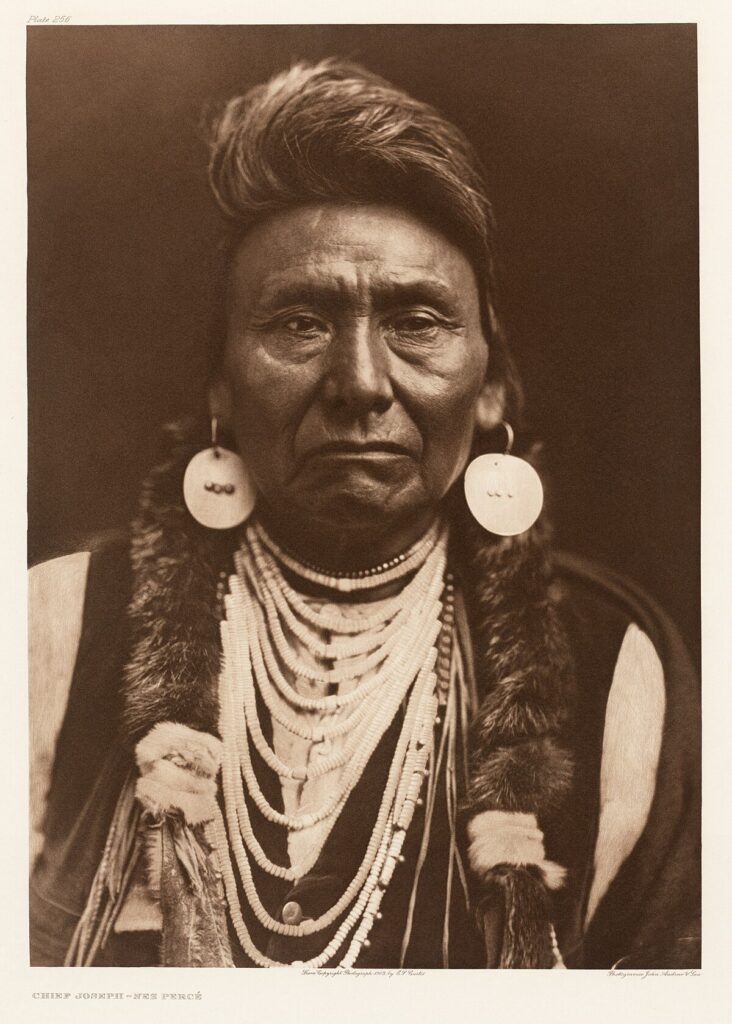

Chief Joseph

Steinbeck might have visited the site of the surrender (October 5, 1877) of Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph and his bedraggled band of 87 men, 184 women, and 147 children, just 40 miles from the Canadian border near Chinook, Montana. Joseph, who did not regard himself as a war chief, led his people on a 1,170-mile flight from the Wallowa Valley in Oregon to the Bear Paw Mountains in north central Montana Territory. The Nez Perce were pursued along that immense refugee odyssey by various companies of the United States Army, in what amounts to a running defensive battle of more than a thousand miles through the Bitterroot Mountains, Yellowstone National Park, and the Crow Indian Reservation before Joseph made a last-ditch run for the Canadian border, on the other side of which, in “Grandmother’s Land” (i.e. Queen Victoria), they would be safe from further pursuit. It was there that Joseph is said to have declared, “I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed … It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death … Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sad and sick. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed … It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death … Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sad and sick. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph

Whether Joseph actually spoke these words or sent them by messenger to the U.S. Army’s Nelson Miles and O.O. Howard is now regarded with considerable skepticism. It may well be that Joseph’s interpreter turned whatever the Nez Perce leader actually said into the poignant and poetic words that are attributed to him. How much of this was known to Steinbeck is unclear, but he gives a fair amount of space in Travels with Charley to the plight of the Nez Perce in 1877. For a time, the Steinbecks lived near the home of Charles Erskine Scott Wood in Los Gatos, California. We now know that Wood transcribed and almost certainly embellished Joseph’s remarks. Wood later wrote, “No one was told to take it down. I was not told. The speeches of Indians were not considered important. I took it for my own benefit as a literary item.” Steinbeck writes that when Wood spoke in the 1930s of the battle and surrender, “his memory of it was very clear and very sad. He said it was one of the most gallant retreats in all history.”

Steinbeck also might have visited the confluence of the Madison, Gallatin, and Jefferson Rivers at Three Forks, Montana, an important Lewis and Clark site, but also the site of one of the most famous incidents in early Montana history, “John Colter’s Run for Life.” Colter, one of the ablest veterans of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, turned back before the expedition reached St. Louis and became an important figure in the Upper Missouri fur trade. In 1808, he was trapping along the three forks of the Missouri when he and his partner John Potts were intercepted by a band of Blackfeet men defending their sovereign territory (and the beaver, sacred in their culture) from the trespass of white extractionists. Potts was killed immediately, but Colter was stripped naked and given a brief head start before the Blackfeet warriors chased after to kill him, too. He outran his tormentors, turned and killed the lead warrior, and then submerged himself under driftwood in the Madison River until the Blackfeet gave up and left the scene. After that, he walked 225 miles barefoot to Fort Raymond on the Bighorn River. You can imagine — almost. In Steinbeck’s time, Colter’s run would have been regarded as a hero story. In our time, we are sufficiently aware of the dispossession of Native American homelands and resources to view the incident through a more complex and ambivalent set of lenses. It would be interesting to know what Steinbeck would have thought of the cultural revolution in America from 1960-2024. He made his epic journey in Rocinante just before the 1960s heated up and changed everything.

Montana Highway 59 from Miles City to Jordan goes through some of the most desolate and least populated country of the United States. It’s perfect! It was north and west of Miles City that the Smithsonian’s William Hornaday (1854-1937) had a conversion experience in 1886 worthy of St. Paul and rededicated his life to the mission of saving the buffalo from extinction. At the time of Lewis and Clark, there may have been 60 million buffalo in America, from the Appalachians to the Rocky Mountains. There were too many to count, William Clark wrote in July 1806, and too many even to reckon. By the time Theodore Roosevelt shot his first buffalo in 1883 in southwestern North Dakota, and Hornaday, saving them from extinction in 1886, fewer than 1,000 buffalo were alive on earth. (Today, there are about 600,000 buffalo, mostly in private hands.) I’m used to being alone — I love to be alone — in big, empty places in the American West. Still, when I drive offroad onto gravel in that district northwest of Miles City between the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, I feel a touch of agoraphobia. I’m a little nervous, even in a splendid vehicle.

A Few More Montana Byways for Your Consideration

In the unvisited country of extreme southeastern Montana, you’ll discover the town of Ekalaka (population 397) and Medicine Rocks State Park. Young rancher and cowboy Theodore Roosevelt camped there in 1884 on his way to the Bighorn Mountains, where he would kill his first grizzly bear (and much else!). The Medicine Rocks are so enchanting they’d qualify as a national park in many states. The same is true of Makoshika State Park just outside Glendive, which is also the home of the Creationist Fossil and Dinosaur Museum. If you ever visit Glacier National Park in northwestern Montana and thread your way east along the fabulous Going to the Sun Highway, suddenly, almost instantly, you drop off the Rocky Mountains and onto the Great Plains. There are about a dozen such places in the West — including I-70 from Idaho Springs to Denver — but the view of the plains just before you drop down onto the Blackfeet Indian Reservation is my favorite.

I’ve been to the actual “source” of the Missouri River down near Idaho and Yellowstone National Park at Upper Red Rocks Lake on local highway 509 and Meriwether Lewis’ source at Lemhi Pass west of Dillon. Like so much else that is magnificent in the American West, these places aren’t on the way to something or somewhere else. You have to want to visit them. And they deliver greater satisfaction because they are not casual encounters.

This is just a short list of my favorite places in Montana. I’m sure my Montana friends will accuse me of ignoring other extraordinary places in the state, but I am ready to hear their recommendations. In fact, I’m scheming of a way to spend a month exploring Montana alone sometime in the next two years.

Think of it. Two of the great national parks of America are in Montana. Two of the world’s great rivers are in Montana, the Missouri and the Yellowstone. Seven Indian Reservations: Cheyenne, Fort Peck, Fort Belknap, Rocky Boy, Flathead, Blackfeet, and Crow. Montana has 100 named mountain ranges! The storied Powder River in southeastern Montana passes through some of America’s prime antelope and ranch country. The Powder is where the Lakota leader Crazy Horse wanted his reservation — but we assassinated him first, on September 5, 1877. It was along the Yellowstone in eastern Montana in 1872 that the Lakota leader Sitting Bull walked calmly out onto the grass within rifle range of the U.S. Army, sat down, and quietly smoked his pipe while U.S. soldiers attempted to kill him. He finished a pipeful of kinnikinnick, calmly got up, and sauntered back to safety. That’s how you become a legend.

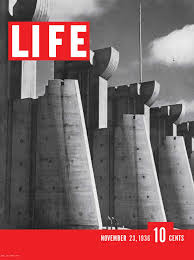

One of America’s great dams is located in eastern Montana, Fort Peck, photos of which graced the first issue of Life magazine on November 23, 1936, thanks to the artistry of photographer Margaret Bourke White. Not far from the Fort Peck reservoir, one of the great conservation experiments in American history is underway. The American Prairie Reserve is creating a vast buffalo commons in partnership with U.S. environmental agencies and Native American tribes. Their goal is tens of thousands of genetically pure bison within an unfenced commons of more than three million acres. Their work is controversial — local ranchers and communities are not so sure — but when they succeed, they will have created a world heritage site that will draw enlightened tourists from all over the planet, especially Europe.

In a few days, I’ll be floating in the sacred White Cliffs section of the Missouri River southeast of Fort Benton, Montana, a stretch of the 2,540-mile Missouri only accessible by canoe, Meriwether Lewis’ “scenes of visionary enchantment.” The White Cliffs offer one of the most spectacular canoe rides in the world. Lewis and Clark came through twice and the river is so hemmed in there by cliffs on both sides that we know we are floating precisely where they labored and precisely where they camped. I’ve got two dozen fellow Americans champing at the bit to get out on the river. The temperature is very high, and the river is low, but as the presocratic philosopher Heraclitus said, “You can never walk into the same river twice.” This is my 23rd time through the White Cliffs. I’ve never had a bad experience. The river is new every time, and I am … well, I cannot really say new anymore, but ready for a new experience.

John Steinbeck was a Californian and later a New Yorker. Mostly, he hugged the coasts. He traveled the American heartland a few times in his life (1902-1968), and on the great Travels with Charley journey he saw Montana — sort of. He would have loved the state even more if he could have lingered on its backroads and byways. And, like so many others, he would have considered purchasing a place out here. He could have exchanged quips with David Letterman or (in his time) NBC’s anchorman Chet Huntley. Steinbeck would indeed have looked up U.S. Senator Mike Mansfield, a friend of JFK and LBJ, one of the most progressive politicians in Montana history.

I repeat, as a lover of California, Utah, Wyoming, and the Dakotas, if there were only one state, it would have to be Montana. Because I live so near, I spend more time here than in any other state except North Dakota. And I am only getting started.

Editors Note: Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.