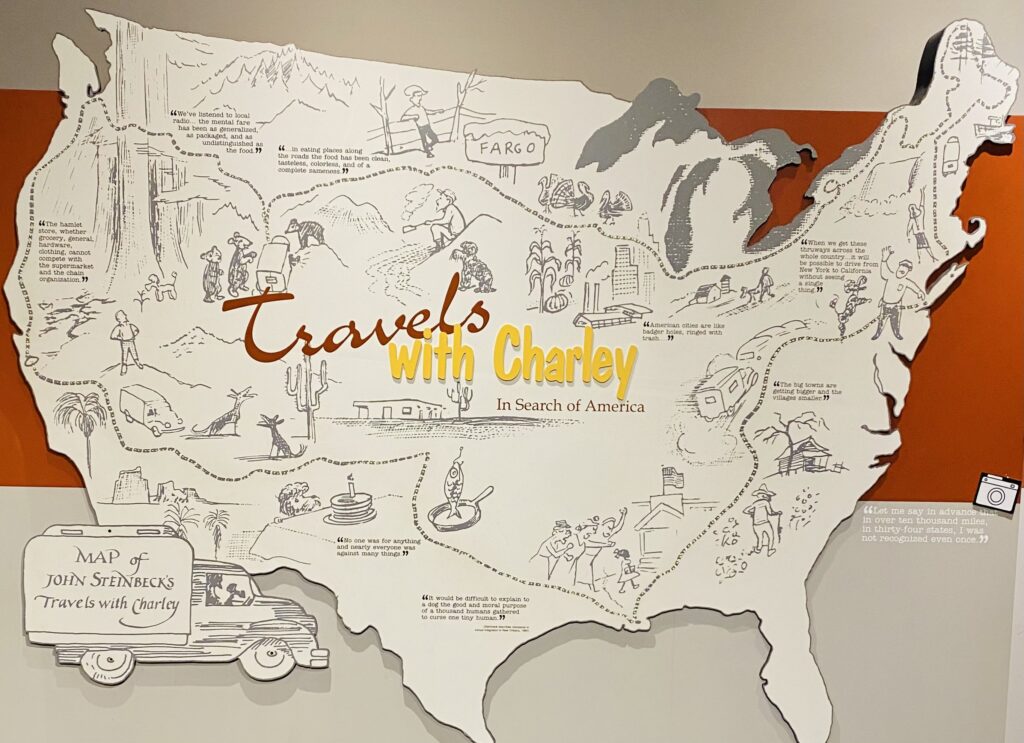

It has been about four weeks since Clay began retracing John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley Tour. Shadowing the famous author’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA, Clay notes some advantages and disadvantages between his trip in 2024 and Steinbeck’s 1960 journey.

John Steinbeck stopped every week or so to reflect on what he had seen and experienced and what it signified about America or himself in 1960. I’m a month into my trip, somewhere in Ohio, vaguely on my way to Chicago, and with a bit of time on my hands, I thought I might summarize my sense of what is different in a journey of this sort today, in 2024, from a similar (but far from identical) journey in 1960. Here’s my preliminary report.

I have so many advantages over Steinbeck — all except transcendent talent.

Here’s a short list.

1. Air conditioning. Fortunately, he was traveling in the autumn, but we now have sophisticated climate control systems in our vehicles. When Steinbeck wanted to open the windows, he had to hand-crank them.

2. His seat did not recline. My grandfather had a 1957 I-H pickup. It held you upright, and the cushions were adequate. Over time, you could feel the springs beneath the fabric. My vehicles, including my pickup, have seats that can recline enough to make it possible to get a good night’s sleep. The pickup has electric seats and lumbar support, too.

3. Safety features. Back then, the dashboard was made of metal. There were no seat belts, shoulder belts, airbags, or emergency flashers. My father, otherwise enlightened, removed the seatbelts from our new Ford Falcon in 1964.

4. Steinbeck had power-assisted steering. That was the Beta or VHS tape phase of what would become true power steering a few years later. He reported being exhausted after driving his GMC pickup a couple of hundred miles. He actually did fairly ridiculous calculations of how much arm and foot muscle was expended in driving such vehicles.

5. There were no RV parks in his time. He often squatted on private property, which I would not dare to do today. I’ve had two run-ins with property owners on the Little Missouri River, and though both ended civilly enough, in both instances, I was required to acknowledge that I was trespassing and that one does not have the right to trespass on private property.

6. I have GPS and Google navigation. This matters much more in the East and New England than it would west of the Mississippi River. Steinbeck was frequently lost. He got lost on the final day when he ventured back into New York City over the bridge. But it is more than just the accuracy of GPS guidance. If you constantly fumble with a map or an atlas, you are not concentrating enough on the road. This always matters, but it matters most when driving a trailer or a truck camper.

7. The roads are infinitely better today than in Steinbeck’s time. I don’t mean the interstate highway system, which he decried, but I am certain that he would have used it and loved it when he was trying to eat up miles, as when he flashed across the Great Plains from Chicago to Seattle to meet his next rendezvous with his wife, Elaine. The non-interstates are dramatically safer today, with better and wider shoulders. Most secondary roads have passing lanes every few miles. Road signage is better now. When my family drove from Fargo to Fergus Falls, Minnesota, in the 1960’s on old U.S. 52, there were dangerous concrete curbs at the edges of the narrow roadway. And, as William Least Heat Moon explained in Blue Highways, the interstates have drawn 90% or more of the traffic off the secondary and tertiary roads, making them much safer and dramatically less congested.

8. Steinbeck had only a tube-type AM radio. Today, we have entertainment systems. He could have made a Steinbeck playlist if he had lived in our time. He liked to write to the sound of great symphonies. My pickup is ancient (2013), but it has AM/FM/XM and (because it is so old) a CD player, and I can plug it into my smartphone with a USB cord. I can remember traveling America with only an AM radio. There was a compensatory pleasure in spending time fine-tuning the radio to get the best signal available in what was (especially in the West) a media desert.

9. I’m trailing an Airstream, which would be like a five-star hotel by the standards of Steinbeck’s 1960 truck camper. He had a small chemical toilet. No shower. The barest of refrigerators, and they didn’t work well back then. He had to take down the dining table and convert that space to a bed when he wanted to sleep. I believe this caused him to stay in motels more often than he admits because setting up such a bed at the end of a long day is tedious. He reports that when he was in a hurry to get started the following day, he frequently just slept on the dining couch. The lights in a modern camper are excellent. I have his and hers reading lights over the bed. He often read by gas lantern.

10. Gas stations in 1960 were just gas stations. Perhaps they had a glass cabinet of candy. They were cramped. Usually, they had no more than two pumps. You could only fuel up with the help of a gas station attendant. Most people paid cash for fuel back then. If you wanted food, you had to find a grocery store or a ma-and-pa store. Today’s “fueling stations” are spectacular. You can cross the country today without ever going into a grocery store or a restaurant by selecting good plastic-wrapped sandwiches, boiled eggs, or individual packets of cheese, or — if you were starving — those hot dogs that have been slowly turning all day in the open air!

11. Fast food was in its infancy in 1960. There were just 228 McDonalds in 1960. Although Burger King had been created in 1953, there were only 274 stores by 1967, a year before Steinbeck’s death. The first Arby’s opened in 1964, Subway in 1965. If you were looking for fast food in Steinbeck’s time, you either found a locally owned drive-in or looked in cities for White Castle or Big Boy. Steinbeck railed against the coming of commercial homogeneity in America, but sometimes you need provender. The easy-on, easy-off fast food options of our time — as well as nationally franchised motel chains and fuel stations — make long-distance traveling easy and efficient. They have also helped to hollow out the downtowns of America, local restaurants, and regional variety. I can imagine Steinbeck preaching jeremiads against fast food, but I can also imagine him saying, “You know, the Big Mac is pretty darn good,” at least until he read Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation.

12. Today’s audio devices are tiny, inexpensive, and — used properly — they can provide state-of-the-art audio recordings. He would have had to take a reel-to-reel tape recorder to capture sound or conduct interviews. If you wanted “video” in Steinbeck’s time, you had to have an 8mm movie camera. I know from experience all the things that can go wrong with 8mm cameras. I routinely record interviews on one of five devices (a teeny digital recorder, a handheld digital recorder, a recorder the size of an old transistor radio, a 35mm SLR camera, and my smartphone).

13. We have the internet, with everything that represents, makes possible, distorts, and damages.

14. When Steinbeck wanted to be in contact with his wife Elaine, he had to find a phone booth, work through an operator to place a collect call, and hope that Elaine was actually at their phone in NYC or Long Island. The calls would have been brief, even for a wealthy man like Steinbeck, because they were horrifically expensive then. When I was a boy, if we called my grandmother long distance over in Minnesota except on holidays, the first question she asked was if anyone was sick or dead. Today, I can text anyone I know, send instant photos or short videos, or speak with my daughter on FaceTime or WhatsApp.

15. Books on tape. I can listen to thousands of books, some of them read by outstanding professional voice artists. Steinbeck carried a just-published copy of his friend William L. Shirer’s massive Rise and Fall of the Third Reich in 1960, but he was too tired at the end of a long day to read much. Today, he could have listened to all 57 hours and 11 minutes of R&FoTR read by the outstanding Grover Gardner as he drove America. I am sure he would have done that if such a technology had existed.

16. Weather prediction has become a reliable science and art in our time. Not so, then. The other day, I heard a massive storm with tornadoes would rock the country’s central section. Fortunately, I was hundreds of miles north of the storm, but if I had been in its path, I would have found a giant concrete warehouse and parked adjacent to the northeast wall to wait out the trouble.

Probably, there are more advantages today that do not come readily to mind. Still, if you think about the accumulated advantage of all of this, you may wonder (as I do) in what sense this guy is actually retracing John Steinbeck’s 1960 Travels with Charley journey. Indeed. I wonder how much I would like this journey if I tried to travel in an identical truck camper (the chemical toilet alone makes me shudder), with its unreliable and primitive amenities and the rigor of driving a pickup with such rigid seats, no air conditioning, and only power-assisted steering; if I used only AM radio, called home from whatever’s left of phone booths, found few or no RV campgrounds, and drove on narrow hair-raising roads choked with slow-moving traffic.

I can report that I have been on the road for a month and have not stayed in any motel or hotel. I have yet to purchase a single fast-food meal. I have stayed in commercial campgrounds as seldom as possible. At least six times, I have been in state or county campgrounds without water or electricity. However, I regard staying in contact (at least with my website and social media platforms and my daughter in Great Britain) as so vital that we splurged on the Starlink system, which usually (but not invariably) permits me to contact the outside world.

So, What Were Steinbeck’s Advantages?

The list is shorter but of extraordinary importance.

1. His pace was necessarily slower. The pace of America was dramatically slower then. He had a better opportunity to just amble along, passing through the center of countless villages, towns, and cities. If you want to reconnect with America, that pace is superior.

2. He wrote letters to communicate. Most of them went to Elaine back in New York. Since he does not seem to have kept a journal, they formed the basis from which he later wrote Travels with Charley in 1961. I lament the disappearance of the handwritten or typed letter. He took a manual typewriter with him. How often he used it is unclear, though my sense is not much. He preferred to write his notes and letters by hand.

3. America was more regional and varied then. The great homogenization of America was only beginning. He lamented the loss of regional accents, vocabularies, and ethnicities, but compared to today, the America of 1960 was a dizzying patchwork of localisms and regional diversities.

4. America today is more sophisticated and savvy, but there has been a palpable loss of trust and innocence. Even if you haven’t read Bowling Alone, you know the thesis: that voluntary associations and group activities have been eviscerated by all sorts of factors, including, of course, home entertainment systems. In most places, the Masons, Elks, Eagles, Optimists, and Kiwanis are either gone or on life support. People don’t know their immediate neighbors now. There has been an atomization in virtually all aspects of American life.

5. America has always had a potent politics, but the great paralysis had not set in yet in 1961. Steinbeck heard the presidential debates in 1960. John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon were civil and respectful of each other. Aside from the John Birch Society, few Americans believed that people of different political persuasions threatened the future of democracy. Three times in three days of the last week, while minding my own business at my campsite, strangers have ambled over and within minutes spewed exceedingly angry opinions, all three assuring me that the 2020 election was stolen, that Joe Biden is only a figurehead and Obama is really running the country “from the basement,” that the people who did the rioting on January 6 were either Antifa or the FBI, and that there will be civil war if the Democrats steal the 2024 presidential election. I do not exaggerate. Because I am trying hard to listen to America, I have not done much more than ask a few careful Socratic questions, but none of these bothered to ask me what I think. So far, I have not been approached by a single Democrat, as far as I can tell, and the number of what might be called centrists has been negligible. Perhaps I am choosing the wrong campgrounds!

6. I have no Charley. Steinbeck rightly understood that everyone loves a good dog, with the possible exception of the governor of South Dakota. When he stopped, he turned Charley loose, and Charley served as his ambassador. It worked almost every time. Because I chose not to take a dog, I have no such advantage, and I believe it has limited my contact with people along the way. My daughter lived in New York for five years. She dog sat for a few weeks, and suddenly, scores of people in Central Park were friendly and eager to engage in conversation.

7. But the great difference is that John Steinbeck was one of America’s great writers. He had long since perfected his craft. Now 59 and in declining health, he felt he had nothing to lose or gain in the fall of 1960. He knew exactly how to shape a journey narrative — having written one of history’s best — and you can feel in the prose of Travels with Charley that he was at ease. He knew, too, that whatever he wrote would be read by hundreds of thousands and perhaps millions of readers in America and beyond. He says he traveled incognito, but this was not entirely so. When he needed to get special treatment, he could invoke his celebrity. As the author of Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, he could instantly make doors open for him should he wish.

Still, I am having the time of my life. I am not homesick. My little private aluminum domicile is working admirably. The only errors are human. I’m seeing the vastness of America and appreciating American landscapes in the East and Midwest that I did not know very well, having always been a denizen of America west of the Mississippi River. Even at the University of Minnesota long ago, I lived on the west bank and only walked over the Mississippi River bridge to study Latin at 8 a.m. five days a week. I’ve had the opportunity to interview (on audio and video) three of the great John Steinbeck scholars in America — so far. I’ve listened to everyone I have met with an open ear and, I hope, an open mind. I’m struck by the friendliness of the people I’ve encountered, at least until the conversation strayed to “you know what.” Gasoline is not exactly cheap (except by European standards), but it is affordable. America has a very welcoming infrastructure for the wandering class. As I sit at a metal picnic table in central Ohio, the giant Denali rig next to me (currently uninhabited) has an above-ground sewer line with a series of slightly shorter plastic supports worthy of the Roman aqueducts. This keeps things moving to their ultimate destination. Most of the rigs I see have at least two bathrooms and three large-screen televisions, one deployed outside the rig for alfresco viewing.

I’m keeping in mind that Steinbeck’s journey was much more strenuous and difficult than mine, more romantic in essential ways, and perhaps more authentic. Having pounded the pavements of America for a month now, I have increased respect for the near-elderly man who undertook the big journey back in 1960. He was more truly out of contact for most of the adventure than I could possibly be in this America. No wonder he was sometimes lonely and desolate. If you are squatting on someone’s dairy farm in Connecticut, with no neighbor 20 feet away in either direction, without any immediate way of connecting with the broader world, you will feel profoundly alone at times. The fear that you will be awakened in the middle of the night by a curious or enraged property owner changes the equation dramatically. And, finally, I believe strongly that by 1960, Steinbeck had become so dependent on the unfailing love and solicitude of his third wife, in his most successful marriage, that his heart and often his mind were back at Sag Harbor, not in the “monster country” he was ostensibly attempting to explore.

I have two-and-a-half more weeks of Phase One of my great adventure. I miss my big library back home but little else, and because I am a moving target, my Amazon.com purchases have declined to a trickle. So something good comes of everything.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures and subscribe to our newsletter.