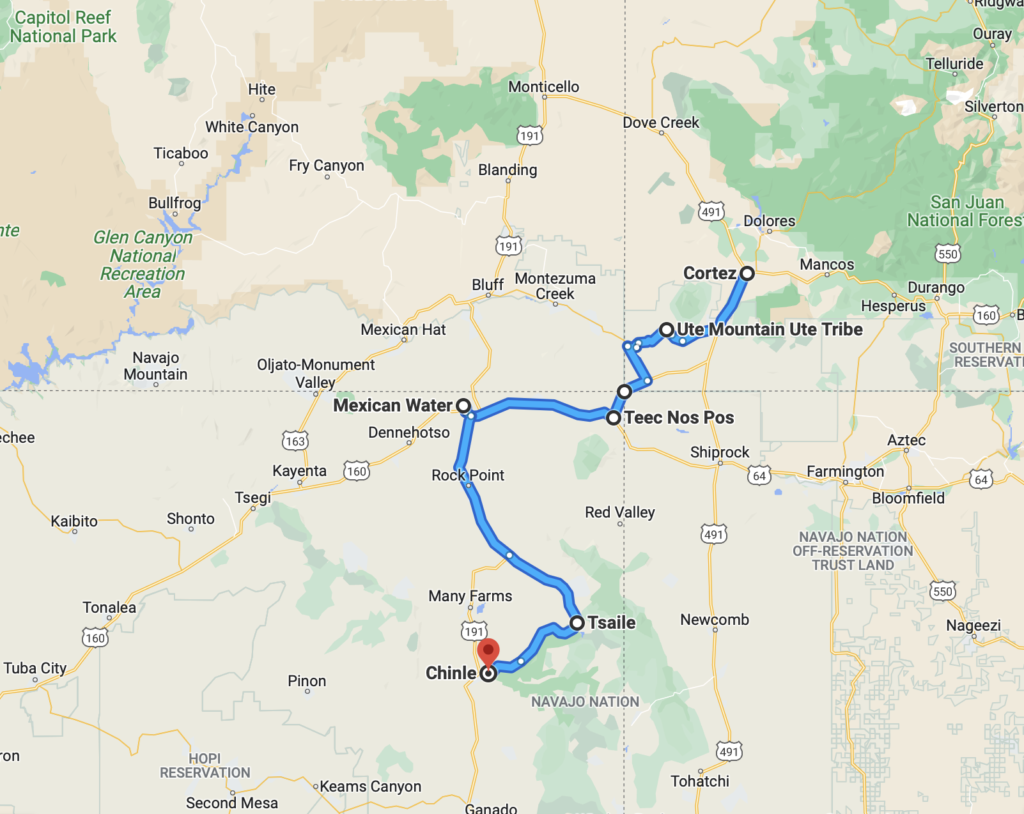

Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

This is six in a series of dispatches from Clay Jenkinson chronicling his recent journey with two compatriots following the Colorado River and neighboring region. Traveling south from Cortez, Colorado the team stopped to visit the 7,700 acre Ute Mountain Ute Farm and Ranch. Later that day they traveled through Four Corners, eventually reaching Chinle, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation, adjacent to Canyon de Chelly. The two-week expedition explored the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm and Ranch Enterprise is nestled up against Ute Mountain and its related peaks, a couple of dozen miles south and west of Cortez, Colorado. It was our first stop on Tuesday. The Ute Mountain Ute tribe manages a non-traditional 7,700 acre farm there. Thanks to a 1988 agreement with the U.S. Government, the Ute Mountain Ute are now entitled to a 24,517 acre-foot allocation of water per annum. That doesn’t mean they always get their full share, especially in recent years when there has not been enough water in McPhee Reservoir to meet all its users’ needs. The tribe has 110 center pivot sprinklers, but only a fraction of them have been used in recent years as the drought in the American West deepens.

Under the 1988 Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement Act, the Bureau of Reclamation agreed to supply municipal, industrial, and irrigation water to the 2,000-member Ute Mountain Ute tribe as part of the Dolores Project. The basis for the agreement was the 1908 Supreme Court case Winters v. United States, in which the court determined that when the U.S. government “reserved” parts of the West as Indian reservations, they were obligated to reserve enough water to supply the reasonable needs of the Native Americans who lived there. Native Americans sometimes counter that it was they who “reserved” a small portion of their ancestral homelands from total appropriation by the white occupiers.

We spent a couple of hours in the offices of the farm with Simon Martinez, who is the director and manager of the operation. He explained the origins of the farm (and ranch). Simon was in a celebratory mood but also extremely busy when we visited because the tribe has been informed that it should be able to get its full allotment of water this year. The tribe is scrambling to open several fields that have been fallow in recent years.

Simon explained that the farm tries to make sure that 60% of its workforce is Indigenous. In his careful and thoughtful way, he explained that a good portion of his work involves the nurturing of the careers of Indigenous workers. All personnel managers in all enterprises have complicated relations with their work staff, of course, but in Indian Country it takes extraordinary skill, patience, delicacy, and commitment to make sure Native workers have every chance to succeed in their work. The legacy of conquest and the brokenness of many Native American communities in America require extraordinary leadership. When we left at mid-day, all three of us immediately wanted to discuss this. What we had learned is that the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm and Ranch is a social development program and not just a capitalist enterprise.

In addition to the farm, the enterprise operates a milling operation called Bow & Arrow Brand, opened in 2014. The mill sells cornmeal, including non-GMO, gluten-free and kosher products to grocery stores and other niche markets. The cornmeal is used to make chips, polenta, pasta, grits, and cornbread. We toured the mill with the help of the farm’s irrigation manager Michael Vicenti and mill manager David Pettigrew. The noise was deafening but the cornmeal was just beautiful.

The farming methods at Ute Mountain Ute Farm and Ranch are industrial: tractors, planters, cultivators, combines, eighteen-wheel grain trucks, some of them soon to be satellite driven. This is an irrigation farm watering desert lands with imported water and center pivot sprinklers. The farm uses best conservation practices, however, including drop nozzles along the pivots, and several micro hydropower units that turn some of the flow in the feeder canals to electricity, which in turn, offsets some of the power needs of the farm. Michael Vicenti drove us out to one of them and explained its workings. It was not running at the moment, because the fields have not been planted yet.

Our time with Simon Martinez was deeply gratifying. He’s an amazing man with a huge and complicated management portfolio. And yet, he seemed perfectly relaxed in our two hours together, even though he had several Council Zoom meetings before and after our arrival.

It’s not clear how important the proceeds of the farm operation are to the Ute Mountain Ute budget, but the farm is a major employer of Native Americans in the Cortez area, and its psychological benefits are mighty and deeply significant. The unemployment rate in the Ute world is high. During our time on the farm, we met several men in their 30s and 40s who started out, years ago, performing the most basic work of the farm, hauling rocks out of the fields, and now hold important management positions that they earned through hard work and discipline.

After several centuries of colonial oppression and exploitation, and the crushing of Native traditions as a deliberate political strategy of the United States government and its settler communities, Native American communities of the twenty-first century are making a remarkable comeback. There are still a great deal of poverty and poverty-related social challenges in the Ute world, but enterprises like this have a significance far beyond their profit and loss sheets. We came away from our tour feeling good about the future.

We all agreed that we want to return to the farm during harvest, to see all that corn abundance come off the land and make its way into bags ready to ship to retailers around the United States. We made our visit just when the spring operations at Ute Mountain Ute Farm were beginning to heat up.

A Detour and Search for the True Four Corners

Leaving Sleeping Ute Mountain and driving south I had to beg my two colleagues to visit Four Corners. They were snooty about it. As we closed in on the turnoff in mid-afternoon, they both looked into the back seat in the hope that I was asleep. But no. So, we paid our fare and bounced up to the parking lot. I don’t know what I expected, but this celebrated place had a seedy and neglected feel. It was still just March, of course.

We hustled up to the plaza to get to the exact meeting point of four sovereign states: Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. Surely some kind of cosmic vortex was there, I reckoned, waiting to electrify my consciousness. I’ve wanted to visit Four Corners all my adult life, and more so after seeing the new National Lampoon’s Vacation movie a few years ago. I took photographs of tourists figuring out ways to be photographed in all four states simultaneously. It was like a game of Twister on cold concrete. One man in sweats attempted the yoga wheel pose, tummy arched up to heaven, two hands in two states, two feet in two others. On this 45 degree spring day, there were not more than 50 people on the whole site. There was no line at the plaza, but a nearby sign said, “Limit Three Photos Only.”

Perhaps six or seven vendor windows were open in the huge ring of kiosk slots that circle the square, with a range of t-shirts, Four Corners trinkets, and some Navajo jewelry. My spirits were elevated. I was thanking Thomas Jefferson for insisting on rectangular states in the Ohio country and beyond. In his landmark 1784 Plan for the Government of the Western Territories, Jefferson laid out two rows of square states west of the Appalachians and gave them cool names like Polypotamia and Sylvania and Cherronesus. His vision was that every western state would be square and identical in size until we reached California with its sad irrational coastline. You can see Jefferson’s sameness-of-size template in the tier of Great Plains states: North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, each embracing two degrees of latitude. And you can see true rectangles in Colorado and Wyoming and approximations of rectangles in Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. It can be argued, therefore, that Four Corners is the “most Jeffersonian place in America,” as well as the most purely rational place in America. Put it this way — remove the signage and the concrete map and who would ever recognize the boundaries of these states? These are merely artificial lines in a sinuous and undifferentiated landscape that sweeps off to the horizon in every direction. At least if you place your border at the Rio Grande or Lake Michigan or the Red River of the North, you recognize it when you get there. In Jefferson’s fantasyland, every line is straight even if it bisects a lake or mountain or gulch. As I looked on in a daze of admiration for Jefferson, I was also wishing we would adopt the European metric system — finally.

But just then, in the middle of my revery, Frank, with a twinkle of malice in his eye, informed us that the monument is approximately at the true intersection of four states, but not precisely. The actual intersection, he said with authority, is approximately 1,800 feet west of the plaza. I suppose because Frank could not talk me out of the Four Corners detour, he reveled instead in shattering my illusions about the place. So much for the spiritual vortex.

Things like the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England, Four Corners in the southwest, and the Geographic Center of North America in North Dakota matter to me. The Enlightenment replaced the old metes and bounds system of land surveying (the rock where the creek comes in, or the giant apple tree on the corner of the lot) with pure geometry. Latitude (easy) and longitude (very difficult). America’s adoption of the rectangular survey grid system (thank you, Mr. Jefferson) was a triumph of the Enlightenment and maybe the most influential thing Jefferson ever did. Townships, square miles, quarter sections, section lines. So what good does it do to put up a monument approximately where pure mathematics says it needs to be? You can put up an interpretive center near Thoreau’s Walden cabin and nobody suffers. But if you fudge the exact this or the exact that, you have defeated the whole purpose. I’m quite serious. One chapter of my most recent book, the Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is about this issue. Get it right or get out of the arena! For fifty years the Geographic Center of North America, Rugby, N.D., where hundreds of thousands of people have had their photo taken, was a fraud. The actual center of the continent was approximately fourteen miles to the south and west of Rugby, in the middle of a pond (a slough as we say in Dakota). Rugby (population 2,509) is merely the nearest town of any size to the geographic center of North America. And now, the reigning champion of the geographic center competition has been shown to be scores of miles west and south of Rugby or the slough. When I discovered this a couple of years ago I was both crestfallen and a little angry.

And that’s how I feel about Four Corners — now, thanks to Frank (aka Beelzebub). The view in every direction is essentially infinite sagebrush country. It wasn’t as if the exact site was unavailable for the erection of a monument. But the exact site would have required some moderate landscaping. And the exact site would have been a little farther from U.S. 160. I wanted to find a picnic table and create a counter sign with a magic marker and a survey stick, and plant it by the gate, warning people: “DON’T BE FOOLED!” “ACTUAL FOUR CORNERS FIVE MINUTES AWAY, EASY HIKE.”

As I studied this question, I found a website belonging to the National Geodetic Survey. One whole page of single-spaced type strains in every possible way to justify the approximate siting of the monument. Listen to this incomprehensible argument:

“Finally, we cannot overemphasize the fact that the aforementioned technical geodetic details are absolutely moot when considering any question of the correctness or validity of the Four Corners monument in marking the intersection of the four states.”

Which is to say, science doesn’t matter — approximate is sufficient? This in a publication by the National Geodetic Survey. But the author goes on:

“Indeed, the monument marks the exact spot where the four states meet.”

It decidedly does not, as the writer admits elsewhere in the essay:

“A basic tenet of boundary surveying is that once a monument has been established and accepted by the parties involved … the location of the physical monument is the ultimate authority in delineating a boundary. Issues of legality trump scientific details [say what???], and the intended location of the point becomes secondary information.”

Did Frank write this essay?

Frank and I bought Navajo frybread with powdered sugar at one of two food kiosks open at the site so early in the season. To lighten the blow of his geographic revisionism he bought me a two-inch hand-painted magnet with each state presented in a different color. $1.50. He presented it to me with great ceremony. But I cannot be bought off so easily. We drove on. As I sat in the back seat contemplating the utter absurdity of human existence, Frank whistled and chortled up front.

Towards sundown we wound up at Thunderbird Lodge at Chinle, Arizona on the Navajo Nation.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.