Day One: Bismarck to Sioux Falls

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.

This June I had a speaking engagement in Sioux Falls, South Dakota and another in Vail, Colorado. In the spirit of Listening to America, I decided to drive rather than fly. There were several places I wanted to visit along the way. So, I packed my car with camping equipment, cameras, books aplenty, camp chairs, and my favorite blue Yeti cooler, one of the miracles of modern chemistry and engineering. On Monday, June 12, I drove out of Bismarck and into the American heartland.

My first stop was Whitestone Hill, where a mostly forgotten battle took place between the U.S. Army and a village of Lakota Indians.

Whitestone Hill is a grass hill in south central, North Dakota, near the South Dakota border. It is the site of the bloodiest battle in North Dakota history. On September 3, 1863, U.S. General Albert Sully attacked a large peaceful Lakota encampment here. He killed more than 200 Lakota and took another 156 as prisoners of war.

Why the attack at Whitestone Hill? As this story unfolds, 99% of the population of what is now North Dakota was Indigenous. Nomadic Natives, the “Sioux,” the Assiniboine, the Ojibwe, moved across an infinity of grass prairie with no fixed permanent home. Sedentary Natives, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, had semi-permanent towns along the Missouri River and lived in domed earth lodges, grew corn and other crops, and sent out hunting parties for fresh supplies of meat. The white population in 1863 was no more than a few hundred. Significant white settlement of North Dakota would not commence for another 20 years.

The people we used to call the “Sioux,” called themselves the Dakotah, which translates as “the people.” They spoke a roughly common language with distinct regional dialects. The Dakota lived more towards the east, in Minnesota and Wisconsin and northeastern North Dakota. The Lakota were the classical “western Sioux,” and they lived mostly west and south of the Missouri River. They never came together in one immense encampment. The Minnesota “Sioux” consisted of several subgroups. For the purposes of this story, it makes sense to think of the Dakota Indians as living mostly in Minnesota and the Lakota as living in central and western North Dakota. They were related and there was considerable interchange, but they were clearly distinct.

Backstory: Why Was the United States Army Carrying War Across the Red River Into North Dakota in 1863?

If you squeeze a people ruthlessly enough, and treat them as subhuman, when they can no longer find a way to eat, they are going to burst into a spasm of desperation violence. That’s what happened to the Santee Dakota of Minnesota. By the time of the Minnesota Uprising of 1862, the Santee Nation had been coerced or pressured into signing away the great majority of their territory and were confined in a very narrow reservation along the St. Peter’s or Minnesota River near today’s New Ulm or Redwood Falls. The full reservation was just 20 miles wide, 10 on either side of the river.

The white invasion of Minnesota had been sudden and profound with the white population of the Minnesota Territory growing from 6,077 in 1850 to 172,072 in 1860.

By this point most of the Santee were dependent on the U.S. government for their basic subsistence. In exchange for their homelands, they had been promised regular rations. Those rations were often late, sometimes ruinously late, and the traders and agents were overall a corrupt lot.

The late Stephen Ambrose wrote about this in Crazy Horse and Custer, my favorite of all his books. He said the pattern was set early and it never wavered. Push them. Press them. Surround them. Bully them. Insult them. Until finally some little incident touches off a brief fierce spasm of grief, rage, resentment, and longing. Then the government tells the American people that the “Indians have committed border depredations that must not go unpunished.” And then there is war, after which the U.S. wrings even more concessions and cessions out of the Native Americans. Here’s Ambrose:

“From the time of the first landings at Jamestown, the game went something like this: you push them, you shove them, you ruin their hunting grounds, you demand more of their territory, until finally they strike back, often without an immediate provocation so that you can say ‘they started it.’ Then you send in the Army to beat a few of them down as an example to the rest. It was regrettable that blood had to be shed, but what could you do with a bunch of savages?”

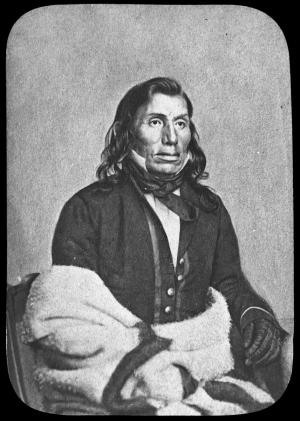

Informed of the Natives’ suffering, the Minnesota trader, Andrew Jackson Myrick channeled his inner Marie Antoinette. “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung.” Whether Myrick voiced those exact words is disputed, but his statement went viral. On August 17, 1862, five young Santee men killed five white settlers in Acton, Minnesota. Now the Santee leadership decided that because the whites were going to respond to the killings with violent reprisals, maybe the best course of action would be to strike the white invaders with a spasm of violence. The warring faction was led by a man named Little Crow. His hope was to drive the white settlers out of the Minnesota River Valley altogether. The Santee struck hard. They killed hundreds of white settlers (some say over 750), burned down homesteads, barns and mounds of hay. The settlers and the Minnesota militia killed many Natives. Eventually 2,000 Santee surrendered or were taken into custody. Of these, at least 1,658 were noncombatants.

Little Crow and 150-250 followers fled to the plains of what would become North and South Dakota, and parts of Canada. This western migration was one source of all the sorrow that was to follow. A military commission composed of officers from the Minnesota militia, spent just under six weeks trying the Natives, who usually did not have counsel, did not know the charges that were leveled against them, could not speak English, and may have had nothing to do with the uprising — the records show that in at least a few of these cases a completely innocent man was condemned to death. The commission sentenced 303 Dakota men to death. Fortunately, President Lincoln took an interest in the case, reviewed the files carefully, and reduced the number of men to be executed to 39.

On December 26, 1862, 38 Santee men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in a specially constructed mass scaffold. What happened in Mankato that day remains the largest mass execution in American history. The rage of the white settler population is understandable. The rage of the Santee Dakota is understandable. The war was not inevitable. It was brought on by white indifference and malfeasance. The reprisals in 1863 and 1864 which carried the “Indian wars” out onto the plains of Dakota for the first time, were unnecessary. They did more damage than good. Instead of ending warfare between whites and representatives of the great Lakota-Dakota world, they brought on 30 years of bloody struggle.

In the wake of the uprising, Congress passed legislation authorizing severe reprisal and punishment. The eastern Dakota reservation in Minnesota was abolished. Congress declared any previous treaties with the Santee null and void. The government rounded up all the Dakota individuals it could find and placed them on riverboats bound for what’s now South Dakota.

That’s the necessary background to better understand what happed at Whitestone Hill. In 1863 and again in 1864 the government of the United States and Minnesota sent out punitive military expeditions to drive all Sioux-related Natives farther west on the plains of the Dakotas, and to attack Native encampments. The idea was to hit the Dakota-Lakota with such force that they would never wage war against white America again.

September 3, 1863

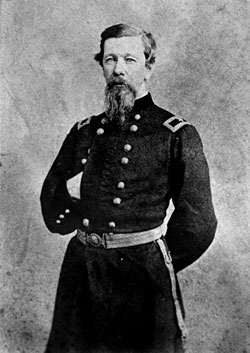

It was on September 3, 1863, that Brigadier General Alfred Sully attacked a village at a grass knoll known as Whitestone Hill. It’s located near today’s Kulm, North Dakota. Sully’s force of 1,200 soldiers, about half of which engaged in the battle, attacked the Dakota-Lakota village. Sully and his men killed more than 200 Natives, including women and children. He took 156 prisoners and destroyed every bit of Native baggage, food, and shelter — according to historians — 500,000 pounds of material. It may be that several Santee who had played active roles in the Minnesota Uprising were mingled among the Lakota at Whitestone Hill. But the great majority of the people Sully attacked were entirely innocent of the events of Minnesota. They were aware that the U.S. Army was stirred up and likely to lash out indiscriminately, but they believed they were beyond harm’s way, and they were minding their own business on a grassland hundreds of miles from the Minnesota River Valley.

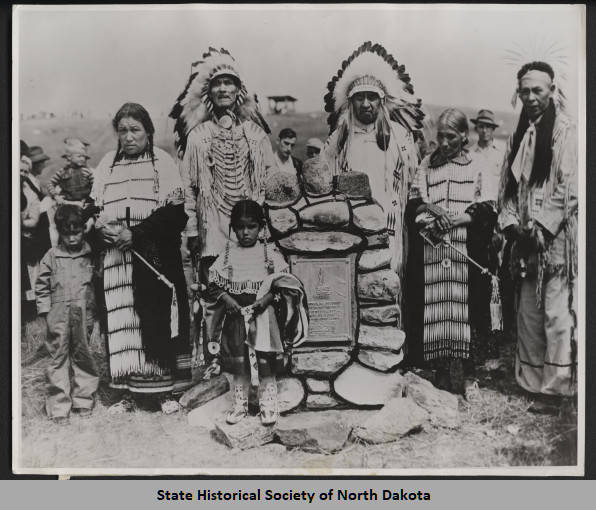

I spent about an hour at the Whitestone battle site. A close friend on staff at the State Historical Society of North Dakota informed me that the agency has new signage ready to go up at Whitestone Hill. That is good news. Because if a person who knew nothing of American history landed there, s/he would have to conclude that a glorious battle had occurred there and that the victors had chosen to monumentalize their great victory. S/he would see an impressive stone monument to the white soldiers who participated in the battle at Whitestone Hill, some of whom are buried there. At the apex of the hill is an obelisk lifting a trumpeter high into the sky, surrounded by 20 white lozenge gravestones in a square just below the pedestal. No Native graves are discernible at the site.

The Battle of Whitestone Hill (called a massacre by many), was just the beginning. A year later Sully returned with an even larger force, built a fort near the mouth of the Cannonball River and carried punitive war deeper into western North Dakota and eastern Montana, a world away from the events in Minnesota in 1862. The Battle of Killdeer Mountain (July 27-28, 1864) and the Battle of the Badlands (August 7-9) must be seen as quasi-genocidal. As far as General Sully was concerned, and no doubt his superiors back east agreed, a “Sioux Indian is a Sioux Indian,” which meant that the Lakota, distant cousins of the Santee, were effectively just as guilty as the men who attacked white settlers in Minnesota

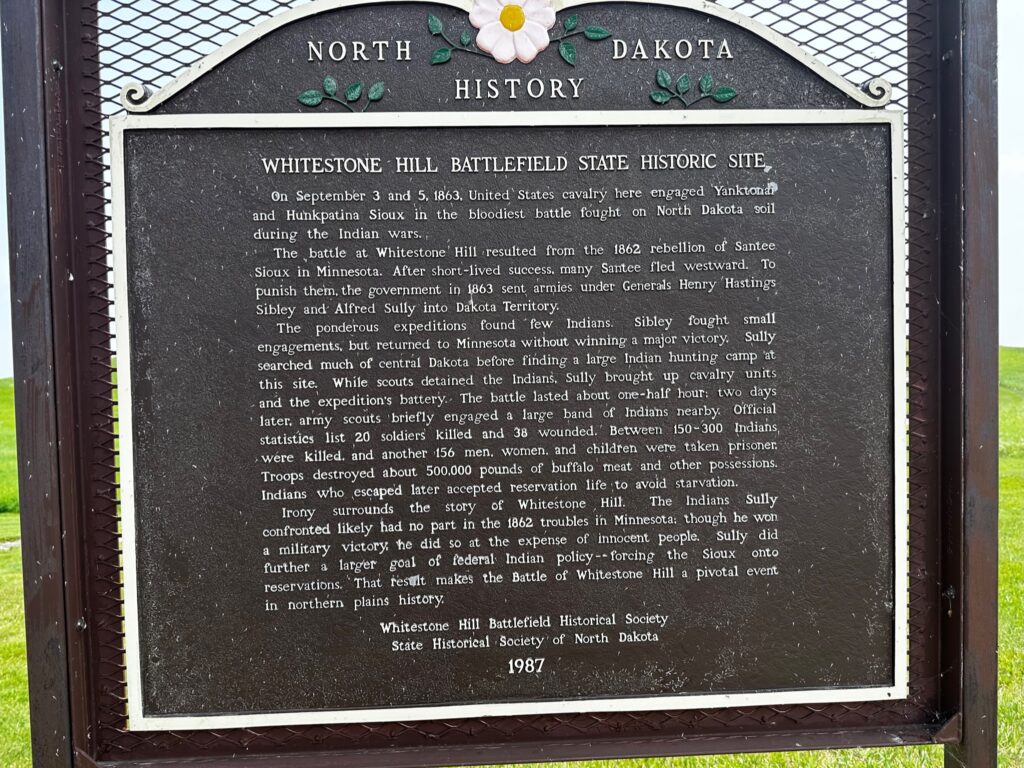

The existing State Historical Society sign is quite good. It was erected in 1987. It starts by acknowledging that this was the “bloodiest battle fought on North Dakota soil during the Indian wars.” It rightly characterizes the reprisal campaigns as “ponderous expeditions.” It notes that after the battle, the U.S. troops “destroyed about 500,000 pounds of buffalo meat and other possessions.”

Most importantly, the sign acknowledges that General Sully was attacking the wrong “Indians.” “Irony surrounds the story of Whitestone Hill. The Indians Sully confronted likely had no part in the 1862 troubles in Minnesota: though he won a military victory, he did so at the expense of innocent people.”

That’s good signage, fair, generous, slightly revisionist, but it is one poster-sized feature of what seems like a monumental tribute to the white soldiers who participated in the ironic attack. The obelisk went up in 1909, when there were no ironies about Native American resistance.

Fortunately, there is one more interpretive panel at Whitestone Hill. On a rock near the parking lot a small metal plaque has been affixed. It was erected “In memory of the Sioux Indians who died on this battlefield September 3-5, 1863, in defense of their homes and hunting grounds.” It went up on July 4, 1942. Strangely, it gives nearly equal space at the bottom to a list of members of the Whitestone Hill Park Board who erected the sign, all white.

Most North Dakotans have never been to the site and are unaware of the battle of Whitestone Hill. Nobody would erect the white monument today. We are discovering in the 21st century that monument-making and erecting is inherently problematic. What one generation or sliver of the larger American community wishes to commemorate may become an embarrassment to future generations. I’m not for taking down the obelisk and the trumpeter or removing the existing signage.

When the new interpretive panels go up, they will be the latest layer that reveals a great deal about the evolution of American memory and our national understanding of the “Indian wars.” When people visit the site, they will see the “phases” of historical interpretation. By leaving everything in place, we invite visitors to reflect on the inadequacy of any single interpretation of complex historical events. History is a series of negotiations about the past. The people who come after, in 2123, may have a perspective on the events of the 1860s on the Great Plains that we cannot now envisage. And that is good.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.