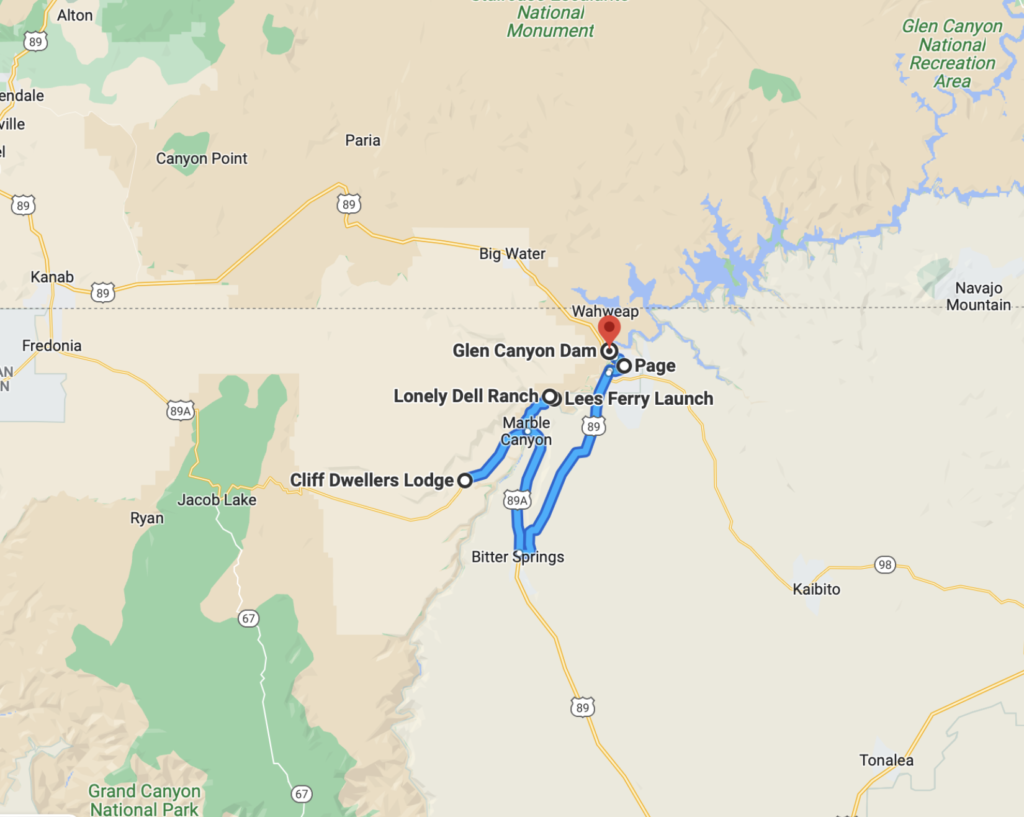

Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Lee’s Ferry and Page, Arizona.

Clay makes a first ever visit to the historic Lee’s Ferry; meets with a long time Page, Ariz. entrepreneur for insights on the region, and encouraged by our intrepid scout, Frank, has dinner at the famous Dam Bar. This is the ninth in a series of dispatches from Clay chronicling his recent journey with two compatriots following the Colorado River and neighboring region exploring the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West.

I’ve read about Lee’s Ferry all my life. Among other things, it is the portal for float trips in the Grand Canyon. Countless stories feature Lee’s Ferry or originate there. I watched several groups tuck their gear into rafts as they embarked on the great adventure. I was filled with envy and a kind of apprehension. Even with the safe, outstanding modern rafts, professional guides, superb life jackets, and helicopters up on the canyon rim waiting for the call, floating the Grand Canyon is not for the faint of heart. A friend of mine’s mother had to be helicoptered out after she suffered from heat stroke. My favorite recent story is narrated superbly by Kevin Fedarko in The Emerald Mile. In 1983, the year of the big water in the Colorado that endangered the integrity of Glen Canyon Dam, three heroic knuckleheads, Kenton Grua, Rudi Petschek, and Steve Reynolds, pushed off illegally from Lee’s Ferry in a wooden dory. They cascaded through the 277-mile Grand Canyon in 36 hours, 38 minutes, and 29 seconds, breaking the previous record of just under 48 hours set in 1980. Some of the other river runners at Lee’s Ferry, grounded by order of the National Park Service, looked on with outrage and admiration as the three wild and crazy adventurers slipped around the corner in moonlight. When they came out at Grand Wash Cliffs, they were promptly arrested.

The ford at Lee’s Ferry was discovered in 1864 by Jacob Hamblin, whom Brigham Young sent to find river crossings in canyon country. The location is named for John Doyle Lee, the adopted son of Brigham Young, one of the participants in the Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7, 1857). Lee was sent in 1871 to operate a ferry at the crossing. Lee had sixty children. He was executed by firing squad in 1877. The ferry operated until June 7, 1928, when it collapsed, drowning three men. The Lonely Dell Ranch and the ferry were operated by a series of LDS families, beginning with the Lees. Now it is maintained by the National Park Service as Lonely Dell Ranch Historic Site. Visitors are encouraged to harvest a modest amount of fruit from the orchards at the site. We spent an hour strolling around the ranch, taking deep breaths amid the fruit trees and trying to get photographs of the whole pastel scene. It is one of the most serene places I have ever been. Anyone who lived there before modern automobile traffic had plenty of time for meditation!

We drove to Page and spent the usual amount of time trying to decide where to lodge. Frank wanted us to stay in some historic clapboard barracks thrown up when the dam was built in the late 50s: musty, spare, stick furniture, weak internet, old pipes. Long on atmosphere, short on amenities. Perfect! Fortunately, the inn had no room, and I vetoed the manger down the street. We wound up on chain motel row, not far from church row, but we wouldn’t be spending much time in our rooms.

Frank knows a Page entrepreneur named Brady Budd. They had a chance encounter five years ago; as Frank put it, they’d “clicked.” Frank assured us that Brady would be a perfect person to interview, and for once, he was right. He was always right, but you know how annoying that can be. Brady came to the hotel. He had a wild and crazy look, like a character from a Hunter S. Thompson book. He was one of the single most energetic men I have ever met. He had big hair and a world-class smile. He was incredibly articulate and forthcoming. He was also extremely knowledgeable and upbeat. We spent more than an hour listening to his views of Page (which he loves), of the dam, which he sees as a done deal (ain’t no turning back now), the prolonged drought (that’s why there’s a dam and a huge reservoir), the local economy (not solely dependent on the lake), the future (bright). He acknowledged that that dramatic drop in Lake Powell was a concern. Still, he reminded us that there had been previous periods of too much water and too little water in the Colorado basin and that things had a way of evening out over the long run. He was by no means naïve about this. He accepted the two big facts: that the waters of the Colorado have been over-allocated (too many users, too little water) and that global climate change has complicated the situation. He said there is plenty to be gained by way of thoughtful conservation. He did not believe that a continued drought cycle or a permanent diminution of the flow would lead to such drastic results as depopulation of parts of Phoenix or Tucson or parched throats in LA. So much of the basin’s water feeds alfalfa fields in the high country and the row crops of Imperial Valley down near El Centro, California, that if things get desperate, the farmers will inevitably have to yield to municipal uses of water. He said, too, that while Lake Powell may be the jewel of the region, it was by no means the sole attraction. The Grand Canyon, Utah’s five National Parks, and other scenic wonders meant that Page would always be just fine, even if things get worse on the Colorado.

I asked him if his views were skewed by the big winter just ending, with 150 to 200% snowpack throughout the American West. Yes, probably, he said, but he was equally concerned that the wet winter and the subsequent rise in Lake Powell (50-80 feet) would “just put everyone to sleep again” and lower the urgency to adopt more significant water conservation measures in the Southwest.

Brady and his friend Randy Reed changed our narrative. They both criticized the national media for exaggerating the crisis. They acknowledged cause for some concern, but to fixate on the precipitous drop in the levels of Lake Powell and Lake Mead is to observe the system in too foreshortened a time frame. If the drought reasserts itself after this wet year and the lake drops another hundred or more feet in the next few years, then it will be time to get deeply concerned. They both said they had been around long enough to know that cycle follows cycle and that any confident predictions of where things are headed will likely be shattered by experience. They urged us not to make too much or too little of this single wet year. This year could mark the end of the drought. On the other hand, this could merely be a blip and after one or two years of good water, the drought will reassert itself. Nor should we make too much of the likely rise in the lakes this year. Even 70 feet is about a third of what is needed to refill the reservoirs and that, if history is any indication, is very unlikely to happen.

When we asked all our questions and Brady Budd answered them with joy and thoughtfulness, he took us to his private museum across town. He’s had many lives. He rode motocross. He competed internationally in sidecar competitions. Brady’s been injured in all sorts of ways. He also lived on Santa Catalina Island off the coast of California. His museum houses several dozen motorcycles, some of them famous. He has a large collection of historic Glen Canyon Dam photographs and other materials. There is a loft apartment above the museum. There are photographs of famous racing figures posing with gorgeous blondes. He has concrete core samples from back when the dam was built. On the wall was a plywood-incised map of Lake Powell that he had dremeled years ago, attempting to get every side canyon just right.

The Dam Bar

Frank assured us it would be a mistake and a loss not to eat dinner at the Dam Bar. He said we could expect to find one whole wall painted to look like the face of Glen Canyon Dam. That’s usually my criterion for fine dining. It’s tucked away in a strip mall along with several more promising restaurants, but we were on a water quest, and we were, truth told, a little excited to see the hydro dam accouterments inside. The place was so popular that we had to wait 20 minutes to get a table. Even seats at the huge horseshoe bar were reserved for special guests — nothing special about us. The whole restaurant evoked the dam. A full-size aluminum boat was poised near the entrance, and some electric transmission coil was 10 feet high blinking neon. All the walls had framed photographs of the construction of the dam. Between sections, there were hanging glass dividers with dam scenes gracefully etched onto the surface.

Fortunately, we had a superb server who engaged us, rather than the other way around, about the purposes of our travels. She told us of her adventures on Lake Powell, where she spends nearly every summer weekend. She urged us to look at several photographs of the dam when we made our way to the men’s room, including one of two workers gazing up into one of the giant diversion tunnels.

The whole experience was like an industrial version of Pulp Fiction. I was hoping that the menu would sport the “Floyd Dominy” slab steak and the “David Brower” tofu bowl, a drink called “the High Scaler,” and another called the “Coffer Dam Cosmopolitan.” For the young, the “Tailrace.” It would have taken Uma Thurman to make things right.

But no.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.