Road-weary and keen to return home to New York, the final leg of Steinbeck’s cross-country journey took him through the troubled South of 1960.

After he reached Monterey and touched base with the Pacific Ocean in 1960, Steinbeck knew he now had to make the return journey to New York. By this time, he was mostly just ready to get home. Steinbeck felt over-stimulated. “My impressionable gelatin plate was getting muddled,” he wrote. I think he was weary of driving America’s highways, and fearful that the journey had not succeeded. He had not found creative renewal and a tuned-up muse. He now realized that his mission “in search of America” was inherently flawed because there is no one America. “Instead of achieving clarity about the essence of America, what I carried in my head and deeper in my perceptions was a barrel of worms,” Steinbeck wrote.

I believe that if Steinbeck could have snapped his fingers and transported himself (and the rig) immediately back to New York without having to face the fact — to himself and his friends — that he had thrown in the towel, he would have done so. But in Huck Finn’s words, “there weren’t nothing to do now” but turn the truck camper around and drive all the way home — with sharply diminished curiosity and enthusiasm.

Because his goal now was to park his truck camper in the driveway of Sag Harbor on Long Island as soon as possible and settle back into his comfortable life with his third wife, Elaine, Steinbeck decided to cross the country rather quickly and narrow his focus. Still, in Monterey, he writes, “I determined to inspect two more sections and then call it a day — Texas and a sampling of the Deep South.”

You can almost hear the fatigue. Therefore, Steinbeck says, “I bucketed Rocinante out of California by the shortest possible route.”

“I bucketed Rocinante out of California by the shortest possible route.”

It turns out he bucketed across Texas, too. We know he stopped in Amarillo to get his poodle Charley to a competent veterinarian. When I was there recently, a local man took me to the probable site of that clinic, where Charley got the professional attention he had needed for hundreds of miles. My Amarillo friends think they have a lead on the family of the long-deceased vet. Steinbeck also replaced his windshield in Amarillo after “a passing car on a gravel road had thrown up pebbles and broken out the large front window of Rocinante.”

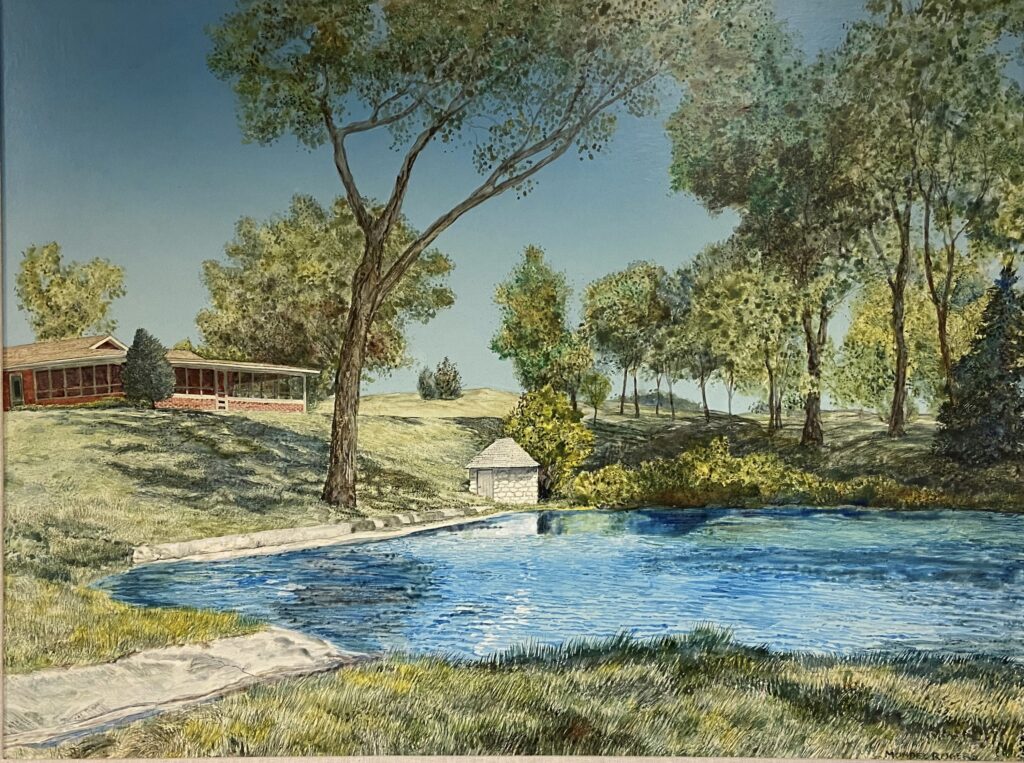

Steinbeck met up with Elaine in Amarillo and drove out to a ranch in the Panhandle that her ex-brother-in-law owned. Steinbeck writes with a bit of faux long-suffering humor, “I am wived in Texas and mother-in-lawed and uncled and aunted and cousined within an inch of my life.” There, they spent Thanksgiving. Steinbeck gave considerable attention to what he called a multi-day “orgy” on the ranch — for the purpose, I think, of using the encounter to exemplify the pride, wealth, confidence, and ostentatiousness of all things Texas.

My Amarillo friend Joe Lovell drove me to that ranch one day in mid-November — with a cracked windshield on the passenger side, so my drive-by photos bear his watermark. (Apparently, he had not taken windshield replacement inspiration from Travels with Charley.) The family that now owns the Thanksgiving ranch is pretty quiet about the John Steinbeck question, essentially near the ho-hum end of the spectrum. But I am glad I saw the ranch headquarters, which Steinbeck described admirably with his usual attention to detail. I’ve spent several years imagining it, and now I can “place” it on an actual Panhandle landscape.

The rest of Texas then becomes a blur. We know he stopped in Austin.

Perhaps because he did not stop and observe the Lone Star State as a real place where 9.6 million people lived, Steinbeck spends a whole chapter writing about Texas as “a state of mind” and “a mystique closely approximating a religion.” It’s as if, when he came to write the book, he needed something to say for all that geography (and road). He needed to write something about the largest state in the lower 48 and the one — along with New York and California — with the most outsized sense of itself. To fill the gap, he reverted to abstractions and what he called “generalities.”

He says Texas is a nation unto itself, with a proud history not limited to the facts. “Texas has a tight cohesiveness perhaps stronger than any other section of America.”

There is no physical or geographical unity in Texas. Its unity lies in the mind. … The word “Texas” becomes a symbol to everyone in the world. There’s no question that this Texas-of-the-mind fable is often synthetic, sometimes untruthful, and frequently romantic, but that in no way diminishes its strength as a symbol.

He was running out of the energy he would have needed to slow down and explore Texas rather than just drive through it.

On to New Orleans and Trouble

By the time he reached the Louisiana border, Steinbeck had narrowed his focus on the “Deep South” to an ugly incident he had read about in the newspapers unfolding in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. Six years after Brown v. Board of Education, New Orleans was just beginning to integrate its public schools. It’s hard for us today to fathom the gargantuan resistance that white Southerners ginned up to maintain apartheid. Governor George Wallace, inaugural address, 1963: “Let us rise to the call of freedom-loving blood that is in us and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South. In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny … and I say … segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

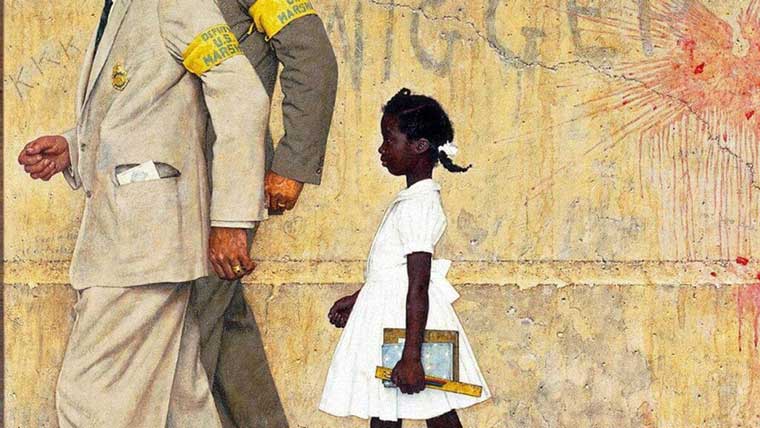

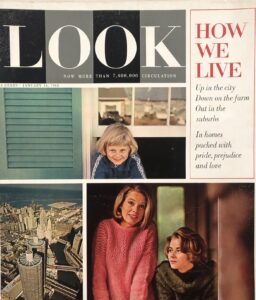

Since mid-November 1960, a racist mob of angry whites had gathered twice a day outside the William Franz Elementary School to shout and spit and stamp their feet and wave homemade signs and throw overripe fruit and jeer and fling the vilest epithets at the U.S. marshals who were escorting the first Black child into the school. Her name was Ruby Bridges. Four years later, the American painter Norman Rockwell placed his painting of Ruby Bridges flanked by federal security in Look Magazine. The painting is entitled The Problem We All Live With. It depicts 6-year-old Ruby walking between the marshals wearing an immaculate white dress, socks, and shoes. We see the security team only from the neck down. Steinbeck called her “a mite.” She is carrying a book, a notebook, and a ruler in her left hand. She faces straight ahead. All five individuals are walking quickly. On the wall of the school behind them are spattered tomato stains and the N-word scrawled in large capital letters.

Steinbeck parked Rocinante somewhere else and took a taxi to the site. The parking lot attendant saw Steinbeck drive up with Charley in the passenger seat. Four times during his time in the Deep South, some local person glancing into the pickup cab and seeing Charley sitting up said some version of, “Man, oh man, I thought you had a n … in there. Man, oh man, it’s a dog. I see that big old black face and I think it’s a big old …” This kind of casual racism sickened Steinbeck to the core.

On this occasion, he worked harder than usual to avoid recognition. He edged his way to the front of the protest rally, jostling with a mob of others who were there to cheer on the worst hecklers.

The leaders of the pack were called the “Cheerleaders.” Steinbeck’s account of what he witnessed that day is some of the best writing in Travels with Charley:

“A shrill, grating voice rang out. The yelling was not in chorus. Each [Cheerleader] took a turn and at the end of each the crowd broke into howls and roars and whistles of applause. This is what they had come to see and hear. No newspaper had printed the words these women shouted. It was indicated that they were indelicate, some even said obscene. On television the sound track was made to blur or had crowd noises cut in to cover. But now I heard the words, bestial and filthy and degenerate.”

Steinbeck’s Paradigmatic Four

It was in New Orleans that Steinbeck met the first of four Louisianans who provided a kind of southern chorus about the emerging Civil Rights Movement, school integration, and the race relations crisis unfolding in the old Confederacy. He met two white men, two Black men; two older Americans, two young men.

The first was an older, neatly dressed white man. They exchanged pleasantries about New Orleans — which Steinbeck knew well — and then discussed the situation. The man took a weary philosophical position. What was happening needed to happen, but it would be agony all around. The man said he knew the South’s “aching past and some of its stinking future.” He wondered if Black people would push too hard and too fast for the white community to absorb. He made what we regard as a racially insensitive comparison between African Americans and domestic dogs. It wasn’t as bad as that sounds, but it was plenty bad. The man said both the North (slave traffic, cotton exporting) and the South were complicit. The resolution was quite likely to involve violence. They said goodbye, and the older man walked home to read, attended by an older Black couple whom he sometimes regarded as family.

The second individual was an older Black man, apparently a field worker in the cotton industry. He was trudging home after a day in the field. Steinbeck offered him a ride. The man was very reluctant, but Steinbeck was insistent. “He wore the battered clothes of a field hand and an ancient broadcloth coat highly polished by age and wear.” It was clear from the start that the man was uncomfortable. “All of him seemed to shrink in the seat as though he sucked in his outline to make it smaller.” After a few minutes Steinbeck asked, “How do you feel about what’s going on?” This was a mistake. The man clammed up and edged as far into the passenger side door as possible. “I don’t know nothing about that, captain, sir,” he said — one of the African American communities’ best survival strategies even as late as 1960. Then Steinbeck said what he was thinking out loud, making his unwilling passenger extremely nervous. “After all, why should you trust me? A question is a trap and an answer is your foot in it.” The old man could only reply, “Would you let me down here, please, captain?” This man had lived his whole life in the American South. He was not going to let himself get drawn into a candid discussion with a stranger, a complete white stranger.

The third encounter was with a young white racist who sat next to Steinbeck at a diner the next morning. He “begged a ride with me,” Steinbeck wrote. After some small talk, the young man asked Steinbeck if he saw “the doings.” As soon as Steinbeck confirmed that he had witnessed the Cheerleaders, the man began to spew his hate. He was enthusiastic with admiration for one of the women who led the protest, a certain Nellie.” Steinbeck took the bait. “I should have grunted and let him read what he wanted in it.” But no. With barely disguised Socratic scorn, Steinbeck challenged his rider. Soon, the passenger was saying things like “somebody got to keep the goddamn n … s out of our schools,” and if the schools are integrated “I’ll sell my life first but I aim to kill me a whole goddamn flock of n … s before I go.” And “you sound to me like a n-lover. I might of known it. Trouble makers — come down here and tell us how to live. Well, you won’t get away with it, mister. We got an eye on you, Commie n-lovers.”

Steinbeck lurched to a stop and told the bigot to get the hell out of his truck. The man slammed the door violently and, as Steinbeck sped away, screamed hatred at him at the very top of his lungs.

Later, between Jackson, Mississippi, and Montgomery, Alabama, Steinbeck picked up his fourth passenger. It was a young Black man, a college student with three fountain pens in his breast pocket.” Instead of raising the issue of the incident at William Franz Elementary, Steinbeck asked his guest about the sit-ins beginning to proliferate throughout the South. The man said “It’s too slow. It will take too long.” And though he admired Dr. Martin Luther King, he felt that nonviolence might not get the job done or not soon enough. Steinbeck said the young man had “a sharp face and the look and feel of impatient fierceness.” When he finally dropped the young man off at his destination, the rider said, “I’m ashamed … It’s just selfishness. But I want to see it — me — not dead. Here! Me! I want so see it — soon.”

And with that, Steinbeck called it a day — in fact, he called it a trip.

Now he rushed back to New York City at the fastest possible pace, stopping only on the side of the highways from time to time to get a nap. His travels with Charley were finished — and yet he had miles to go before he could park the rig and embrace his wife.

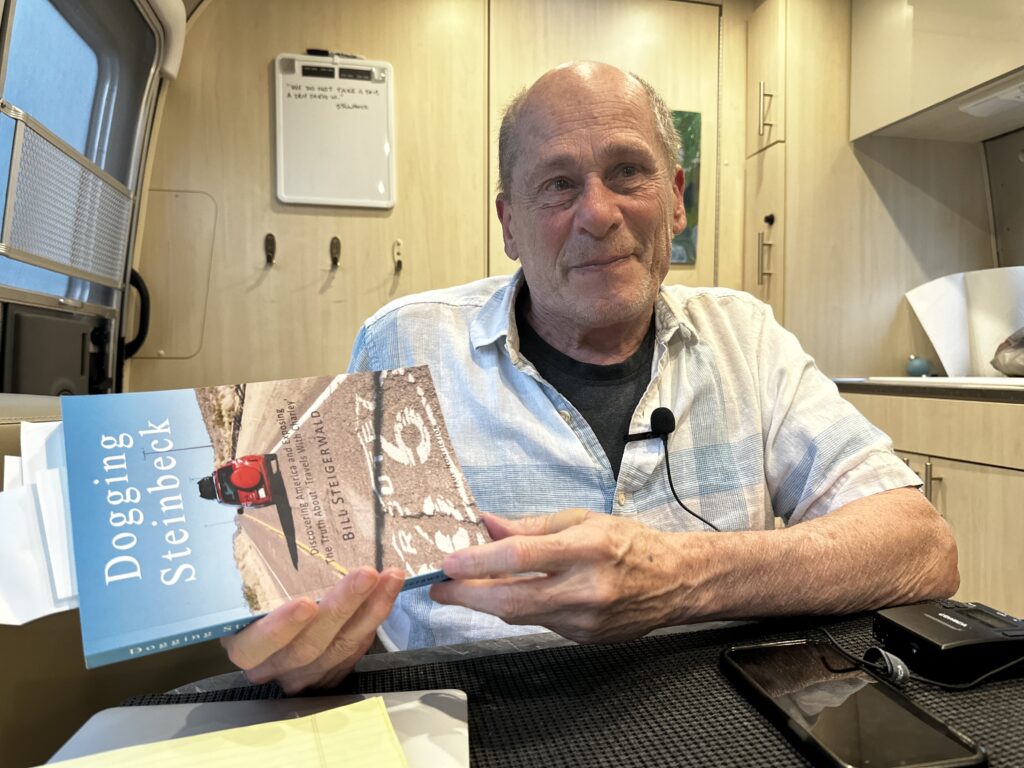

Some critics have questioned Steinbeck’s account of his encounters with the four men of Louisiana. They find the quadruple roster a little too pat, a bit too convenient — essentially two Black men of different generations, one impatient and the other infinitely patient, and two white men of different generations, one an unreconstructed Southern white racist (what is sometimes called a “cracker”), the other a resigned older man who freely acknowledged the necessity of full social and legal integration, but felt apprehension for all the social angst that would be inevitable along the way. The critics are skeptical of such a tidy and tightly patterned narrative, and one — my cranky friend Bill Steigerwald — insists that Steinbeck probably made the whole thing up.

Steigerwald is wrong, I believe.

Did these four Louisiana encounters actually occur? Nobody can know for sure. I come at the famous incidents in Travels with Charley with a default position of trust and belief. I don’t believe Steinbeck made things up, invented encounters, larded his travel memoir with fictional elements and incidents. I believe the encounters actually occurred. Of course, Steinbeck shaped his narrative — the way all storytellers, no matter how punctilious about the data, shape their narratives. It’s certain that he was reconstructing the four incidents months after they occurred. He tells us in Travels with Charley that he did not take notes along the way. As he wrote the book over the winter (mostly in the Caribbean), he “remembered” these conversations with the help of a lifetime of observing and listening to the world around him and putting his observations on paper. He was a novelist. It may be that he streamlined the post-New Orleans conversations to focus only on race relations, and it is possible he embellished each argument, each “position,” to epitomize perspectives along what he thought was the spectrum of opinion about the coming of the Civil Rights Movement to the South.

If the Steigerwald question is, would the account Steinbeck published stand up to a Rocinante camera (a Charlie cam) that recorded every encounter exactly as it occurred, the answer is almost certainly, of course not. But Steigerwald’s demand is unreasonable, naïve, simplistic. I’m glad he raised hard questions about the 1960 journey, the book, and Steinbeck’s precise veracity. Steigerwald has been a net positive contributor to our understanding of John Steinbeck. The questions he has raised have forced everyone who loves Travels with Charley to reread and rethink. Once you get over being annoyed by Steigerwald and wrestle with the arguments he is making, you immediately realize that Travels with Charley is a work of creative nonfiction. The conversation about Travels with Charley is richer for Steigerwald’s insistence that we not take the book as unimpeachable reportage.

I don’t think Steinbeck made things up. I’m arguing that there is no purely fictional encounter in the book and no purely fictional dialogue. I have known for several decades that Steinbeck did not travel America in the role of a talented reporter for a newspaper that employs fact checkers who track down every individual featured in the story and verify that the reporter characterized their views (and their exact words) with 100% accuracy. Steigerwald should have known this going in.

I salute John Steinbeck for taking on some very serious issues in Travels with Charley even if he handled them with considerable grace and — often enough — a lightness of tone. At the top of Maine he returned to the issue of migratory field laborers in America. This time it was a much more positive story. In eastern North Dakota, he raised the question of the marginal status of most performers, actors, and elocutionists in America. In Idaho he explored the burden of being gay in a homophobic society, indeed a homophobic family. In California he wondered if you can ever go home again after living the best years of your life somewhere else. And then, in Louisiana, he wrestled with the central problem of American life: race and the tragic legacy of slavery.

If in getting to the heart of these issues Steinbeck used his great talent as a storyteller and a creative artist to tell truths about America that don’t lend themselves to an exact transcription of on-the-fly conversations, I see nothing to decry. If he had said, in a preface to Travels with Charley, that he guaranteed that every incident, every encounter, every dialogue, every observation on his 1960 journey played out precisely as he wrote it up, with no embellishment of any sort; that every incident occurred precisely when and where he places it in the book; that Travels with Charley was a raw and unvarnished, unenhanced account of his trip; and that he would swear on a Bible that he invented absolutely nothing — then we’d have reason to criticize him and perhaps turn away in disgust.

It saddens me that the great journey ended this way, with Steinbeck horrified, disgusted, depressed, disillusioned, and terribly weary, with hundreds of miles to go, that he saw some of the ugliest energies in America on display, with hundreds and hundreds of southerners gathering to cheer on the self-appointed spokesmen and women of vicious racial bigotry. But in this, he was certainly true to the grim experience that marked the end of his search for America. There is in the book no compensatory incident to restore the balance of the narrative.

That would have been fiction!

With my friends Russ and Liz, and a very delightful African American Uber driver, who gave us several hours of her day to take us through the Ninth Ward, to the William Franz school, and to several places in New Orleans associated with Steinbeck, I attempted to imagine what it would have been like to have witnessed the “white resistance” to social justice at its most intense and the shame Steinbeck felt in acknowledging that this, too, was America.

But I did not want to end my own journey on that note. This is 2024, not 1960. With a very long way to go, we have come a very long way since the end of the Eisenhower administration. In the course of my journey through the American South, I saw plenty of Black poverty. I witnessed what remains of social segregation and race hierarchy. But I also saw white and Black people harmoniously sharing the same restaurants, bars, shops, and civic spaces in communities of various sizes. I saw a range of interracial relationships, some romantic, some not. I hope the hard-won social progress will not stall or go into retrograde motion as the nation veers towards the right and the past.

So, I determined to give my last 10 days of the 2024 journey to a Civil Rights tour of Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. For this, I needed Russ, my compatriot from North Carolina. I’ll have more to say about that soon.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.