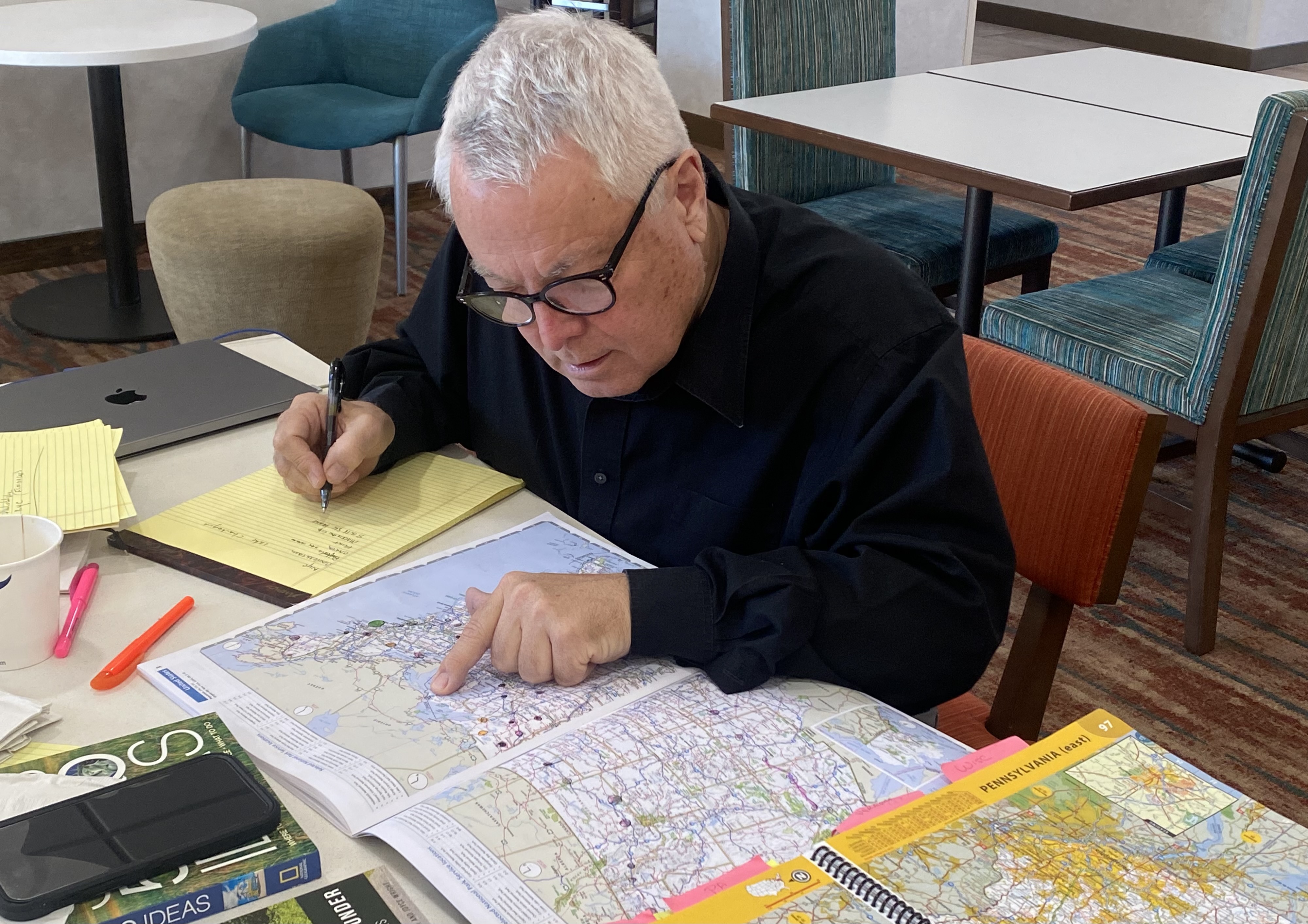

Beginning in April 2024 and concluding just before Thanksgiving, Clay traveled over 21,000 miles and visited 41 states, roughly following John Steinbeck’s route as chronicled in Travels with Charley. Clay notes he undertook the cross-country journey partly to gain his own appraisal of America as it approaches its 250th birthday.

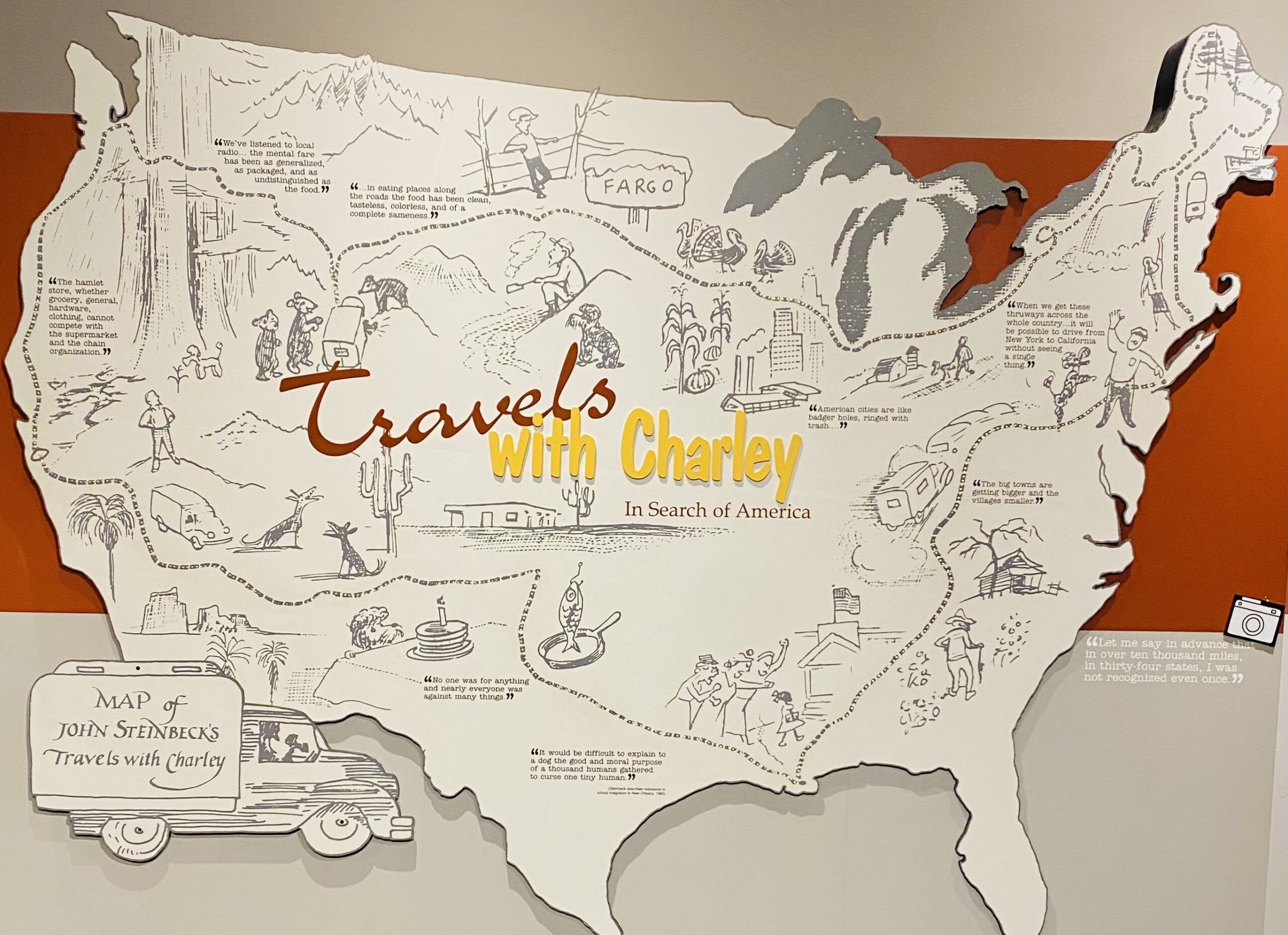

How do I begin to tell the story of my 2024 travels in the tire tracks of John Steinbeck? In 1960, when he was 58, Steinbeck drove a truck camper 11,500 miles around the perimeter of the United States. He was in “search of America” and on a quest to renew his creative juices. Steinbeck took with him his French poodle Charley. His wife Elaine was also with him about a third of the time, though he doesn’t always report that. If the ending of Travels with Charley is any indication, he came home disillusioned, particularly by the racism he observed among southern white people and partly by the growing homogenization of American life. He wrote a beautiful book about his travels, his most personal book, which I regard as John Steinbeck’s confessions.

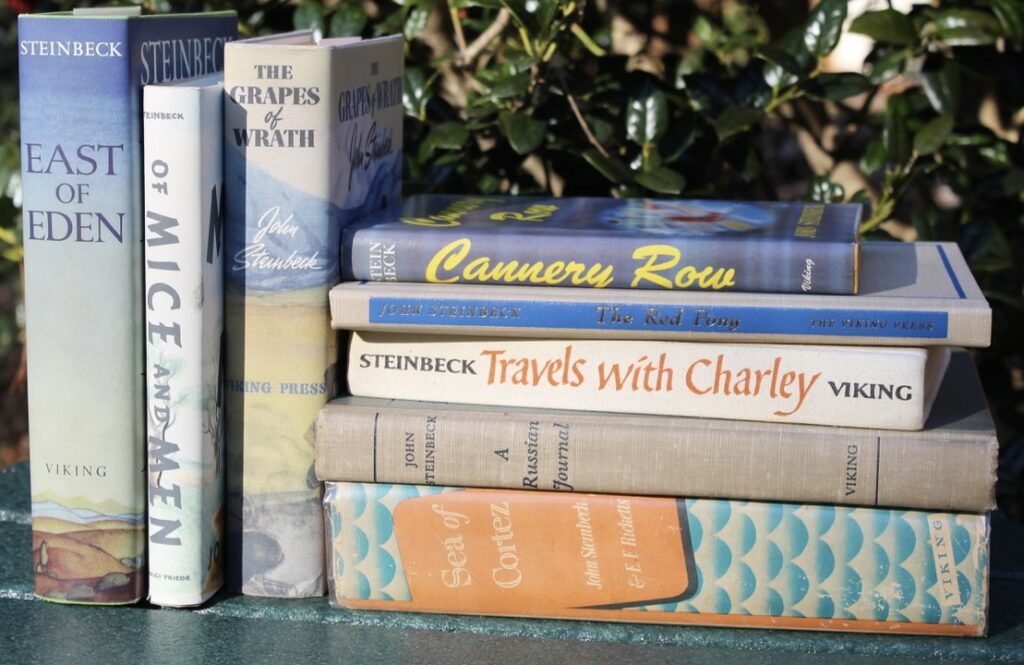

I chose to follow Steinbeck because I admire much of his work; in descending order: The Grapes of Wrath (one of America’s top 10 novels), Of Mice and Men, East of Eden, Cannery Row, The Red Pony, Travels with Charley, The Log from the Sea of Cortez, and A Russian Journal. I wanted to get to know him better, to re-read his books and his excellent letters (he was a prolific correspondent), and to see what I could learn about Travels with Charley by traveling in the footsteps of the journey that was the basis for the 1961 book.

But I confess that I also chose to follow the 1960 Travels with Charley trip because it would provide a useful framework (a baseline itinerary) for my own exploration of America as we approach the 250th birthday of the Republic of the United States, inaugurated by my man Thomas Jefferson on July 4, 1776. Jefferson wrote the mission statement for the American republic. He could not live up to it. The founding generation could not live up to it, and many, perhaps most, didn’t wish to. We don’t yet live up to it. My view is that we must never stop until we get there. In my view, the most distinctive thing about America is that we were invented with a self-conscious set of quasi-utopian documents. Most countries just happened. The U.S. was born of high aspiration. That’s one of the main reasons I continue to cherish Thomas Jefferson despite everything.

I also chose to follow the 1960 Travels with Charley trip because it would provide a useful framework for my own exploration of America as we approach the 250th birthday of the Republic of the United States.

I followed John Steinbeck’s route, but not punctiliously. Almost as soon as I began, I rejected William Least Heat Moon’s fetish about blue highways. I did indeed spend much of my time on secondary and tertiary roads, state highways, and even farm-to-market roads, but I did not shun the Interstate Highway System. Sometimes, I needed to “make tracks” to get to the next destination. I did not want to be confined to the Interstates, but I did not want to avoid them merely to feel virtuous. My pace was much slower than Steinbeck’s. We are unsure when he arrived home in Manhattan in December 1960, but I reckon he was on the road for fewer than 90 days. I spent 210 days out there listening to America, though I gave 10 to my annual Lewis and Clark cultural tour in Montana and Idaho, 12 to the cultural tour I led of Literary England, and I was home for about 20 days between these interruptions. Even so, I felt I rushed too much. As I plan next year’s Lewis and Clark journey from Monticello to Astoria, I plan to slow things down significantly.

Lessons Learned

Lesson One (about Steinbeck and me): you can’t listen to America or search for America if you are pounding the nation’s highways a couple of hundred miles per day. If Steinbeck traveled 11,500 miles in 90 days, that’s 127 miles per day every day. But we know that he lingered with Elaine in Chicago (five days?), lingered with her in Seattle, lingered with her and his family in Monterey Bay, and lingered with Elaine at the Thanksgiving orgy ranch near Amarillo. I’d estimate that he spent 25 days, at least, not making forward progress. It may be closer to 35. If so, when he was driving forward, he was averaging 200 miles per day, at least. We know he crossed North Dakota in a single day: Frazee, Minnesota, to Beach, North Dakota: 408 miles. That’s hard and exhausting driving on the narrow and quite dangerous U.S. 10 through an agricultural state, where farm trucks and other impediments slowed the pace dramatically by today’s standards. Note: one of the glories of the Interstate Highway System is that it shunts most of the commercial traffic, the tractor-trailer traffic, of America to its four broad lanes, thus liberating the secondary roads from all that congestion and making them dramatically more satisfying to the desultory traveler.

My journey took me to 41 states. I didn’t spend exploration time in all 41 and am not out there state-counting. I’ve already been in all 50 states in my lifetime, including Alaska and Hawaii, and in some of the commonwealth outlier places (Guam and the Marianas, for example). At this point, I could not name all 50 state capitals, and I have no interest in visiting every National Park or Monument.

On this journey, I visited six National Parks (Acadia, Theodore Roosevelt, Redwood, Arches, Canyonlands, and Petrified Forest), many state and country parks; two national halls of fame (Baseball, Football); half a dozen graves of individuals I deeply admire; more than a score of museums, galleries, and interpretive centers; and a hundred campsites, mostly RV campsites. Like Steinbeck I avoided the country’s great cities (probably a mistake). I visited as many Steinbeck sites or stops as possible: Sag Harbor on Long Island; potato country in northern Maine (the Canucks incident); Niagara Falls, which he only visited to stave off criticism from his friends; Chicago (one of two great cities I visited), where he and Elaine had an urban luxury reunion, with lodging at the Ambassador East hotel; Libertyville, Illinois, the home of his political hero Adlai Stevenson; Sauk Centre, Minnesota, the boyhood home of Sinclair Lewis; the Maple River in eastern North Dakota (the itinerant Shakespearean incident); the Westgate Motel in Beach, North Dakota, where he stayed (fibbingly) on October 12, 1960; the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, where Charley peed his respect; the (now ruined) guest cabins east of Spokane, Washington, (the closeted gay young man incident); Redwood National Park, where Charley failed to acknowledge the tallest American trees as an ideal peeing opportunity; Monterey and Salinas, his home turf; the Texas Panhandle ranch where he and Elaine spent Thanksgiving; and in New Orleans the William Frantz Elementary School (site of the horrific “cheerleaders” incident), the site of his second wedding (to Gwyndolyn Conger), and the tavern where the wedding was celebrated with Steinbeck’s fellow writers and artists.

With that, I’ve now paid a pilgrimage to most of the major John Steinbeck sites in the United States and several in England, where he attempted to master the geography and the mystery of the Arthurian saga material. That makes me very happy.

Altogether, I traveled 21,114 miles. Gas prices averaged $3.75. The highest price was inevitably in California — in one place just under $6 per gallon. The lowest price was Texas at $2.78 (which is essentially free gasoline). My aging pickup got 15.6 miles per gallon, about eight miles per gallon below what I would like to achieve in year two, if possible, with a newer, more efficient pickup.

Mirabile dictu, I was never stopped by a policeman, highway patrolman, or Texas Ranger, never got a parking or speeding ticket. I was in no hurry. I seldom drove more than 65 mph. My rig broke down twice. My twin RV batteries actually melted somewhere north of Athens, Ohio. The Airstream repairmen who fixed it in Jackson Lake, Ohio, told me I could easily have lost the entire rig or been burned to a crisp if my nearby twin propane tanks had ignited. My friend and host “LP” of the Olympic Peninsula tried to burn out my entire electric system but desisted just in time. I had one minor accident. On my way to visit the outstanding Steinbeck scholar Jay Parini in Middlebury, Vermont, I drove through a narrow covered wooden bridge, which sheared off my Airstream awning. Thus ended my romance with New England’s celebrated covered bridges. The rig now has a couple of dimples where the awning structure pressed into the aluminum.

In all my time on the road I never went to a movie. And I never once turned on the television in the Airstream and never will, because, of course, it is a very slippery slope. In the pickup, I made the mistake of listening to a fair amount of cable media (MSNBC, FOX, CNN, and POTUS) as the election approached. That is one of my deepest regrets. I will not return to those echo chambers during my subsequent journeys through America. I listened to five or six books on the road (a joy Steinbeck did not have in that low-tech era), including several on the explorer Captain James Cook. Improbably, I fell in love with the instrumental music of the Grateful Dead, whom I saw in concert long ago in Minneapolis with my beloved mentor Mike Jacobs and his extraordinary wife, Suzette. I read two and a half hours per day, much less than I like, but the road kept dragging me forward. Alone (and very occasionally with friends), I drank perhaps eight bottles of wine in 21,000 miles (210 days) and polished off (rarely alone) a couple of bottles of gin (with tonic) in seven months.

I never spent a night in a motel or hotel if I could avoid it. When I did, I felt that I was cheating. The one good thing about the occasional hotel/motel was laundry facilities. I enjoy doing laundry on the road because it is intentional and time-concentrated.

I suppose I recorded 15 Listening to America podcasts from the dining room table in the rig and filed 60-75 articles, essays, and dispatches to the Facebook Listening to America site and to LTAmerica.org. We never missed a week with our newsletter, which is little short of a miracle given the required technology. I could not have made this great journey without Starlink Internet. The internet at most RV sites is crummy and intermittent. Fortunately, my good friend Dale M. of Vail, Colorado, realized this problem early on and generously subsidized our purchase of the Starlink apparatus, which never fails unless you don’t have an open view of the northern sky.

I continue to be impressed by the technologies of communication in our time. Steinbeck was hamstrung by the low-tech world he traveled in. He could not record conversations. He could not send email. He could not look something up on Wikipedia or a thousand other sites. There were few RV parks in America in 1960. He depended on phone booths and expensive collect calls to Sag Harbor, where Elaine waited for him. One of the frequent refrains in Travels with Charley is Steinbeck getting lost. I tried to use “old school” maps and atlases whenever possible, but travel today is dramatically easier with GPS systems, both in our vehicles and phones.

John Steinbeck took no camera (alas). I’m surprised that he refused to do so. We know his third wife, Elaine, was the photographer on their travels. It is not altogether clear that she did not take photos when they were together in Chicago, Seattle, the Bay Area, the Panhandle, and Austin, but if she did, the photographs have been lost, hoarded, or sold at auction by greedy descendants. I suppose I took 7,500 photographs altogether (ca. 35 per day), most with my smartphone (lazy but convenient) and many with my 35 mm Canon Mark IV.

A Team Effort

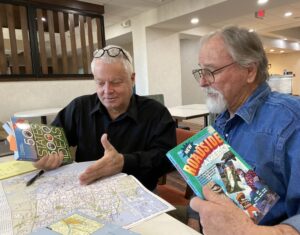

My friend, editor, and videographer Nolan Johnson joined me four times on the journey during the first two of three phases and shot an excellent video of our mutual adventures. Next year, he will play a larger role when I follow the Lewis and Clark Trail across the United States. He (and, on one occasion, his father) brought joy to my otherwise lone journey. Nolan is the editor of the Listening to America podcast. I’d be lost without him.

None of this could have happened without my trusty scout Frank Lister of Escalante, Utah. He knows everyone in the American Southwest (or claims to) and has been indispensable (on short notice) when I needed an RV site. Raina Hall played a key role from Los Angeles. Beth Kaylor of Bismarck played a key role, as did her successor Katherine with a K of Bismarck. Dr. Susan Ryan (Dr. R) of the Crow Creek Archaeological Center joined my LTA partner Dennis McKenna and me at Arches and Canyonlands National Parks if only to humiliate us on the big 11.5-mile hike to the Green and Colorado Rivers confluence. Russ Eagle has been an essential friend, co-adventurer, and podcast host, and the whole thing would have been much less satisfying without him at the other end of a text, an email, or a Zoom call. His wife, Liz, who helps coordinate my cultural tours, is now smug as can be after proving she was right about the world’s greatest gumbo with the help of Ray G. of MeMe’s restaurant in outer New Orleans. And if you have been following my travels, you know that “June” and “Robyn” along the Cache la Poudre River in northern Colorado tried to murder me as just one more incident in their “fake RV host” reign of terror in America. When I visited the Bonnie & Clyde Ambush Museum in Gibsland, Louisiana, a few weeks ago, I thought of them unfondly. Justice will catch up with them at some point — the arc of the universe and all that.

Now I am home, still unpacking, and beginning to try to make sense of it all. This will take some time. This little preliminary report is just designed to help me, and I hope you, make sense of it all.

A Few Initial Discoveries

And now, in a tiny nutshell (much more later), what did I learn? First, per Steinbeck and Travels with Charley. Steinbeck wrote a lovely and entertaining account based on, but not identical to, a journey he took in 1960. The book is great — most people’s favorite Steinbeck book — but the journey was, in my view, largely a failure, in that he a) rushed around the country too much and too fast and didn’t slow down enough to drink it in; b) was by now so dependent upon his third wife Elaine that he was, as he freely admits, “desolate” when he was out there alone; and c) his heart wasn’t really in it. Steinbeck finished the journey because he had started the journey, and it would have been disastrous to throw in the towel, sell the rig in Monterey, and bus or fly home. And yet, the book he produced is important in Steinbeck studies because it is his most personal, revealing, and honest book about his life as a novelist. He is both relaxed in Travels with Charley and willing to lower the protective shield for the only time in his life in a book. We get a serious and poignant portrait of a great American creative artist in Travels with Charley as he senses his declining literary, physical, and psychological vitality. There is some sadness in this, but it gives Travels with Charley an importance it would not have, had he been less frail and fretful in the fall of 1960. We also get Charley, the poodle, who steals the show. Take Charley out of Travels and there is not much of a book. Steinbeck realized this early on. I wish we had a letter in which he came to that revelation. I love Steinbeck more for his vulnerabilities at this ebbing moment of his outstanding career.

I fell in love with America again. In fact, again and again.

Second, what did I learn about myself? This could take thousands of words, but I’ll cut to the quick. I fell in love with America again. In fact, again and again. I love this country. I believe I am the best kind of patriot because I truly love America with my whole being and feel blessed to be an American and no other; and yet I am not afraid to notice what is not just, equal, or finished in the American experiment. I’m deeply disturbed by where we are as a people and a nation — never more so in my life. But the crap that is unfolding in our national politics is no more America — I am indebted to Steinbeck for this insight — than is NASCAR. Both are part of America—both matter. But America is so much more than our national politics, political paralysis, or vicious partisanship; our slow-motion ongoing constitutional crisis. I only had two bad encounters of the hundreds on my journey. I’m sorry to report that they were both with angry MAGA males, who somehow sensed that I was not on board with the populist revolution without ever asking me a single question. I had dozens of good and fruitful conversations with Trump supporters and learned from them. But these two — one in northern California and the other in Wyoming — were purely toxic. Beyond that, I met only good and decent Americans (except for “June” and “Robyn,” of course).

I learned, too, that it is difficult to generate conversations about where America is and where it is headed by traveling from RV site to RV park. My best conversations occurred in National Parks and various interpretive centers, and with old friends I encountered along the way. Steinbeck had the same experience in 1960 — people clammed up when he wanted to inquire about America, particularly politics. That was an election year, too.

Finally, and most of all, I learned this about myself. I thrived out there. I was happiest at 3 p.m. when I pulled into an RV park and got my slot, hooked up to water and electricity, tidied up my Airstream, pulled a camp chair out of my pickup bed, sat in the shade, read a book for a couple of hours, eventually poured myself an adult beverage of some sort, and walked the perimeter of the campground. At night, when I ventured out in the dark, felt the clean air, and looked up at the stars or the moon, I often said out loud, “I am so happy doing this. I am so glad I am here. I love this country. I love America. I am in love with America. More more more more more more more.” I loved sleeping in my own sheets in my own bed in my own rig, with the refrigerator just four feet away and everything I needed close at hand. Despite the disquieting carbon footprint, I felt Thoreauvian and minimalist. After dark, I’d slip under the crisp sheets with a good book and read it for three minutes or three hours, depending on the time. I never once felt unsafe out there. I did not take a gun despite the recommendations of some friends. I slept well, woke early, wrote and read more, poured myself a glass of orange juice, and ate a little yogurt with walnuts and honey. And then got back on the open road. There is nothing quite so exhilarating as ambling along an asphalt highway with a yellow stripe in the middle and something amazing (Monument Valley, the Sierra Nevada, the Yellowstone River, the Pacific Ocean) looming on the horizon. Driving America when it is the driving (not the arriving) that is the purpose — is heaven on Earth for me. The Rubaiyat says, “a jug of wine, a loaf of bread, and thou.” But it could be “a stretch of open road and time.”

Paradise.

There is more to come, at least two more seasons. I’ve got miles to go before I sleep and big promises to keep.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures and subscribe to our newsletter.