There is nothing quite like the magic of traveling America in the fall.

The first thing I noticed upon beginning Phase Three of my Travels with Charley tour of America was the light and temperature of autumn. The summer heat has broken. Now, every morning at about 4 a.m., I have to fire up my Airstream gas heater. It’s heavenly to wake up cold, pull the covers up tight, look out for first light, and want to welcome a guest in the morning who knows how to brew French drip in a travel trailer.

If I were to start this adventure over again, I might begin my journey in autumn, like Steinbeck. He started his Search for America on September 23, 1960. The children are back in school. The RV parks are comparatively empty. The roads are less congested with frantic Americans trying to force-feed a family auto vacation in the 21st century, everyone but the driver working their electronic devices. It gets dark earlier now and stays dark later. Since I refuse to turn on the onboard television system, even during the MLB playoffs, I go to bed earlier than at the height of the summer. The other night, I woke up at 1:30 a.m. thinking it was already morning. I was able to drift off again, but I had already slept almost six hours. I love knowing my linens. And I love my daily onboard shower! The miniature life makes the smallest things satisfying.

On the first day of Phase Three, I stopped for the night at my beloved Devils Tower. It’s a mind-blowing place. It’s the first of our National Monuments, Theodore Roosevelt’s first of the 18 he designated under the 1906 National Monuments and Antiquities Act. A week or so later, I visited Roosevelt’s second National Monument (December 1906), now Petrified Forest National Park.

I was sitting at the picnic table reading under the shadow of Devils Tower when three men walked up to say they had looked up Listening to America (thanks to the Airstream logo) and wanted to learn more. We had a glass or two of wine together in the cool of the evening as we talked about the coming election, the idea of America, and where we seem to be headed. Eventually, they invited me to dinner in their gazillion-dollar bus-sized RV. They assured me that their smoked steaks were the best in the world. The steaks were good, and the wine superb, but their RV was so large, with four big slide-outs, and so luxurious that it didn’t feel like camping at all. There were couches and BarcaLoungers in every direction, a vast entertainment complex, several bathrooms, a complete kitchen, laundry machines, wallpaper, and a front end that looked like the bridge on the Starship Enterprise. I kept looking for the hot tub and the workout room. In short, the sheer splendidness of the RV took the charm of simplicity and roughing it right out of the equation. We could have been anywhere. We certainly weren’t gazing up at Devils Tower.

The second night, I returned to the scene of the crime at the End of Life RV Park in the Cache la Poudre Valley west of Fort Collins, Colorado. After my near-death experience with the two women serial killers six weeks ago, I don’t know what possessed me to return, but I did, and I’m happy to announce that I survived yet again. By the skin of my teeth.

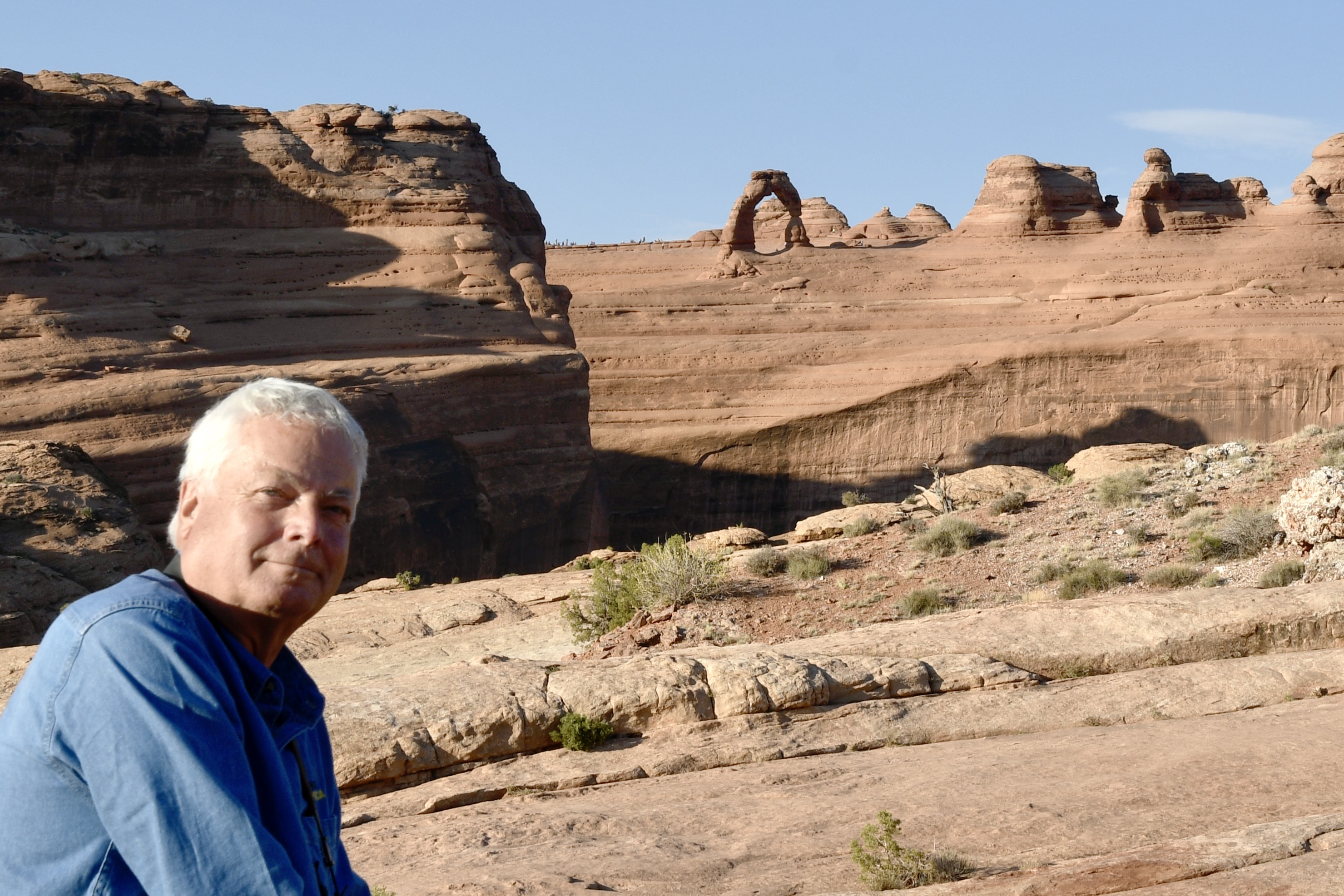

From Vail, where I had the honor of interviewing the great David Gregory, the moderator of Meet the Press from 2008 to 2014, I drove into Utah in tandem with my friend Dennis. We made our way by the enchanted back road Utah 128 from Cisco to Moab, working the s-curves of the Colorado River.

But we could not get to Utah without driving through Glenwood Canyon, 154 miles west of Denver. It’s 12.5 miles long. It was carved millions of years ago by the Colorado River, which begins in Rocky Mountain National Park (La Poudre Pass) and disembogues (at least a trickle) into the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California), some 1,450 miles south and west. In the course of that amazing journey, the Rio Colorado drops about two miles (10,184 feet) and carves out at least 10 canyons (depending on how you count), including, of course, the Grand Canyon, one of the top 10 natural wonders of the world. When you think of the canyons of Colorado, you don’t think of Glenwood Canyon, but it is, in its own way, as spectacular as any in North America, and you can get much closer to the dynamics of the river because the road goes through just a couple of hundred feet above water level. Remember, when Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s soldiers first glimpsed the Colorado River from the South Rim, they reckoned, they reckoned it was no more than six feet across!

As I drove slowly through the Glenwood Canyon (for the umpteenth time), at about 50 miles per hour, on one of the most beautiful highway engineering achievements in American history, I remembered driving it back in the 1980s, when the engineers had not yet figured out how to thread interstate highway (I-70) through so narrow and precipitous a canyon. After a two-year absence from the magnificent landscapes of America, I had flown from London to LAX, interviewed for a job at a southern California college, and — wanting to surprise my parents up near the Canadian border — rented a one-way Avis car (at crippling expense) and drove from L.A. to western North Dakota. Two things happened on that improbable journey that I will never forget.

First, on March 12-13, 1989, North America experienced one of the greatest northern lights displays ever. I was driving across Utah after midnight when suddenly the aurora began to dance the sky; beet red columns of light intermingled with green and blue and an eerie white from the dome of the sky almost to the horizon. The fluorescent light occupied just short of all 360 degrees of a treeless desert. It was like being on some imaginary other planet. Apparently, millions of Americans believed it was the apocalypse or a nuclear attack. It was seen in about half the states and as far south as Guatemala. The phone banks of police stations, the FBI, and the Defense Department were overwhelmed with urgent calls. It was one of the great thrills of my life. I stopped and stood on the side of the endless ribbon of black asphalt with the yellow center stripes just barely glimmering for miles in both directions. My sense of wonder got a vital transfusion that night somewhere near Vernal, Utah.

Later, no longer able to keep my eyes open, I stopped to sleep at an unofficial wayside on the old, narrow, two-lane highway, U.S. 6. The Colorado River was raging just 100 feet away. A railroad line followed the curvature of the river, and freighters sauntered through at careful speeds, thrumming their way west. It would be nearly impossible to be more hemmed in by the great canyon. You never sleep well in such situations, of course. It was a big 80s gas-guzzling car, four-door, brown, with a Mafia-sized trunk. I climbed over into the back seat and used my jacket for a pillow. Fitful sleep, mostly dozing and abruptly waking up in a cold sweat, thinking I had fallen asleep at the wheel. I remember waking up at first light in this magical canyon, feeling all the immensity and romance of America as the light returned to the Earth. I got out and stretched. I drove a few dozen miles and found a diner where other bleary people were hunched over the counter sipping harsh black coffee. No conversation. Everyone looking straight ahead.

“Whither Goest Thou, America, in Thy Shiny Car in the Night?”

My parents were pleased when I finally reached North Dakota, but they did not fall off the couch.

Since 1992, I-70 through Glenwood Canyon is a secular miracle of engineering. I never drive through without appreciating how America sometimes gets things exactly right. The latticework of the lanes performing s-curves in elegant terraces, one on top of the other, letting what Jefferson called “Nature and nature’s God” determine the course of the highway, gives me hope. Even gross things like interstate highways can be poetry if the will is there. There is a bicycle path down along the river that I very much want to explore.

This time, I found myself acknowledging the engineering, of course, but giving most of my attention (aside from not veering out of my lane and ending my adventures!) to the canyon itself. It’s astonishing. The Colorado River is only about 125 miles old by the time it carves Glenwood Canyon. How? How did a river cut 2,000 feet through solid rock? I suppose the answer is a few cubic centimeters at a time for 3 million years. Talk about great engineering feats!

Question. Who was this Glenwood, after whom both Glenwood Springs and Glenwood Canyon are named? How is it that one of the most beautiful canyons of North America is named for some guy we have never heard of? I looked it up. Glenwood Springs, Colorado (at the west end of the canyon) is named for Glenwood Springs, Iowa, which was named (1852) for a Presbyterian minister named Glenn Wood, about whom nothing much is known. So, a white man who never visited Colorado gets a canyon? I hoped that some man named Peter or Biff Glenwood had discovered the nearby hot springs and envisioned a great national highway negotiating its way through someday. But no. Just a faraway Midwestern corn-planting Calvinist named Glenn Wood! If we are going to do some renaming in the American West, this would be a good nominee. I mean no disrespect to the living descendants of the Reverend Wood. But come on — what do even you know about him?

“A Society To Match the Scenery.”

Wallace Stegner called for “a society to match the scenery.” Surely, there is still time in our weird national nomenclature (North Dakota towns are named for mid-level Northern Pacific Railroad executives) and in our social and economic habits to do better, to live the full potential of the world’s only America. Indeed, the West is not merely for extraction.

But these meditations were interrupted by something that appeared in my peripheral vision. I turned my head and saw out of the driver-side window a majestic bird flying along right in tandem down the river canyon. Actually, it was flapping like a much more sleek and elegant duck. I recognized it as a bald eagle — a juvenile bald eagle — and it was flying 250 feet to my left at no higher than the roof of my pickup.

I turned off the air conditioner and opened my window. Philosophical question: if you view the West through the windows of your car, can you say you have experienced the West? I’m not presuming the answer. One drive across the Mojave Desert in August or through Death Valley, I confess to revering the air conditioner.

I fantasized that it was a juvenile making its first great journey down the Colorado River into unknown territory, that — inexperienced at these things — it was having a little difficulty bucking the wind. I slowed down as much as I dared and tried not to get ahead of the eagle. To my utter amazement, it kept pace with my pickup for five full minutes. I’ve seen plenty of bald eagles over the years, but nothing so beautiful and moving as this. If it had been soaring in the full calm majesty of the mature eagle, working the thermals, it would not have been so powerfully compelling, or if I had seen it for 20 seconds and then passed on ahead with the hurrying interstate traffic.

This moment, this vignette, jumped right over my left brain and my consciousness and went straight to my heart and soul — pure wonder. I was graced by a sustained observation of one of the world’s prime creatures, exalted at the top of the chain of avian species all over the Earth. Grace comes when we don’t expect it: that’s how it’s grace.

I do not want to be a bird. I don’t have fantasies of flying over telephone poles like Dean Moriarty in On the Road, working the thermals, and looking for an under-cautious ground shrew or some roadkill. But I would gladly have spent the rest of that day with that young eagle, wondering when it would veer off, when it would find a perch to take some needed rest, whether in a hunting or mere traveling mood.

And then the traffic pushed me down the canyon on the upper road deck, and I lost sight of that majestic being — forever.

There are moments you know will stay with you to the end of your life. Dallas 1963. The Challenger Disaster. September 11. January 6. The aurora borealis of 1989 is one of them (and all that followed in southern California), and my snooze in the heart of the pre-interstate canyon is another (in part because I was a young man feeling his independence with all of his life before him). Remember when you asked yourself what am I going to be? And now the Flight of the Juvenile Eagle. Notice that I have not for a moment “gone Utah litterateur” and said I had an encounter with that eagle, or a relationship with that eagle, or even a “moment” with that eagle. After all, I was driving a V-8 gas-powered pickup and hauling a 23-foot high-end trailer behind me.

I was a mere observer. Even then, I couldn’t give it my full attention because I was thrusting thousands of pounds of metal and plastic over the narrow surface of a busy national highway. On a curvy road. With tunnels! And convoys of 18-wheelers glared at me as they roared past.

When Dennis and I stopped 90 minutes later, we each blurted out “Flight of the Eagle” at the same time. We were giggling and half-huggy with happiness.

And then there was Moab, where it was decidedly not autumn. Ninety-degree days, little or no wind, Lawrence of Arabia sun. The only way we could see autumn was in the reddening of the grass and other foliage and a tiny cluster of yellow cottonwood leaves now and then. Utah in early October 2024 was almost all still summer.

And yet, when I stepped out of my Airstream on my Edward Abbey reconnaissance adventure to meet the day at about 8:30 a.m., I could sense (almost smell) autumn in the air. The first whiff of autumn is one of my favorite moments of the year. The poet John Keats called it a “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, close bosom friend of the maturing sun, conspiring with him how to load and bless …”

We live in a blessed country, and we need to have a rebirth of the right kind of protection and patriotism because no other country has the public lands we take for granted in the United States.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.