“Whither goest thou America in thy shiny car in the night?” — Jack Kerouac

Not long ago, I was sitting at my dining room desk in my Airstream, reading a book about Jack Kerouac. After a long week in Vail, I was weary and camped in an RV park on Colorado’s Cache la Poudre River. I sat sipping red wine (a fine Bordeaux left over from a reception in Vail) and listening to the Grateful Dead, the Beatles, and Joe Cocker. I don’t know what has gotten into me, frankly. Music is usually a small part of my life.

I just read a sentence where the words “Route 6” appear. Immediately, my mind reverted to U.S. 6 through the Vail Valley, where it has been appropriated and diminished by luxury ski condos, edgy restaurants where “presentation” and “locally sourced protein” are important, strip malls, and up-market subdivisions. But seeing the word in a book about Jack Kerouac took me — Route 6 took me — out into Utah, where U.S. 6 becomes one of America’s starkest and most beautiful highways.

On his first (legendary) trip into the American West, Jack Kerouac thought he would take Route 6 all the way to Denver — and beyond.

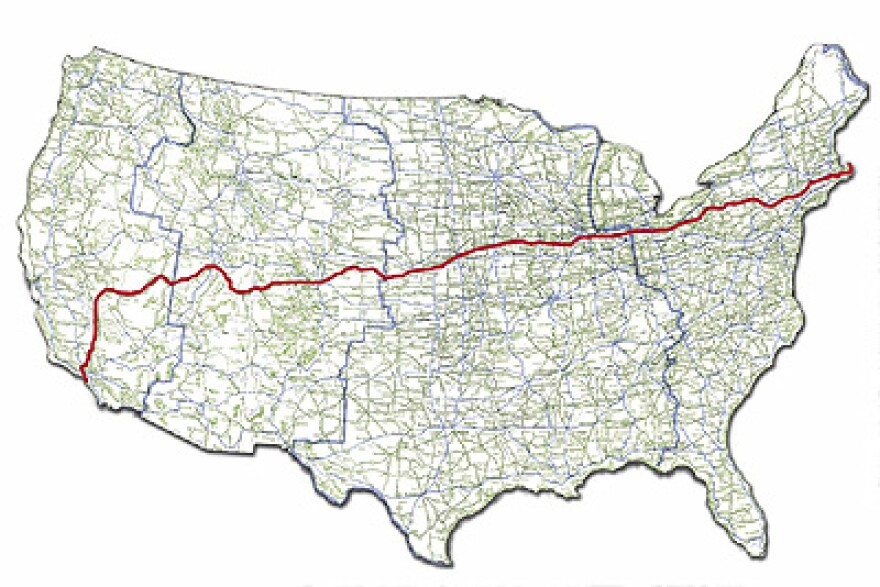

“I’d been poring over maps of the United States in Paterson for months, even reading books about the pioneers and savoring names like Platte and Cimarron and so on, and on the roadmap was one long red line called Route 6 that led from the tip of Cape Cod clear to Ely, Nevada, and there dipped down to Los Angeles. I’ll just stay on 6 all the way to Ely, I said to myself and confidently started.”

The Best-Laid Plans of Mice and Men Go Oft Awry

Kerouac soon learned that Route 6 (at least in the East) was not a good hitchhiker road, and he wound up taking a bus to Chicago to get started.

I admit to being drawn to the “single ribbon of transcontinental highway” idea. For a long time, I have wanted to drive one of the great north-south highways, exclusively from the Canadian border to the Mexican border. Perhaps I’d choose U.S. 85, the first highway that transects the American West, if you regard the Great Plains as the American West. That takes you through butte country, the Black Hills, and the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains. I’d like to affix a GoPro to the front of my vehicle and have it take one photograph every 30 seconds from border to border.

Just as Rivers Serve as an Automatic and Compelling Metaphor for Our Life Journeys, so Roads Invite Us to Muse About the Trajectory of Our Lives

It’s one thing to zig-zag from Chicago to Santa Monica on a wide variety of roads: interstate highways, U.S. highways, state and local roads, farm-to-market roads, etc. That’s generally how I travel. However, it is quite different to follow a single road to the extent that it is still possible. That road might be the legendary Route 66, the highway Steinbeck’s Joads took from Sallisaw, Oklahoma, to the Promised Land. Many of the old national highways have been partly absorbed or obliterated by the interstate highway system — most notably Route 66, which was officially decommissioned in 1985. It seems to me that following a single highway all the way, “acrost,” as Ma Joad says, would be especially enlightening, an intriguing window on America, a semi-latitudinal snapshot. A single highway would be a lovely organizing principle for a long journey, just as following Steinbeck’s 1960 Travels with Charley trek around the perimeter of America has been a valuable organizing principle for my 2024 journey.

When I was in the Pacific Northwest not long ago, on Phase Two of my Steinbeck trip, I found myself out on the Olympic Peninsula. I had to get to Salinas, California, on a specific date, so I mostly drove U.S. 101, a highway I love. It brings back memories of my first trip down the West Coast decades ago, in the first car I ever owned, on my way to a new and exciting phase of my life. I like the fact that, at times, U.S. 101 is an appalling eight-lane traffic corridor near California’s great cities, and at other times, it quiets down and becomes surprisingly narrow and funky. If I hadn’t been in a hurry by then, I would have driven up to the top of the Olympic Peninsula to touch base at or near its northern terminus before plunging south through some of the most beautiful landscapes in America, including the redwoods and of course the Golden Gate Bridge at San Francisco.

“We Do Not Take a Trip; A Trip Takes Us.” — John Steinbeck

But I had promises to keep. And many miles to go.

Kerouac soon realized that the romance of the road works in unexpected ways. Or, as Steinbeck would put it in 1961: “We do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” First, there is the idea of the romance of the open road. How we imagine it as we pore over maps, make lists of places we want to visit or revisit, read books of the road, and imagine the encounters we will have.

Second, there is the actual trip we take. The actual journey challenges the fantasy we concocted back home at the kitchen table. For example, Steinbeck was underwhelmed by Fargo, North Dakota, which he had envisioned as a magical-mythical place, something out of a Kit Carson dime novel of the frontier. “I must admit,” he writes, “the town was as traffic-troubled, as neon-plastered, as cluttered and milling with activity as any other up-and-coming town of forty-six thousand souls.” Kerouac wanted to hitchhike straight from New York to Denver — and beyond. This was in 1947. He was about to inaugurate the Beat Generation. Nobody stopped on Route 6 to pick him up and he got soaked from a rainstorm. He took the bus. Somehow, Kerouac manages to make a Greyhound bus seem romantic. I remember them before smoking was banned. Not even Simon and Garfunkel could make a long Greyhound ride (back then) seem heroic.

I understand why Kerouac wanted to follow U.S. 6 to Denver. I spend much time devising whimsical journeys — cross the nation eating only at Pizza Hut. Cross the nation listening only to the complete works of Charles Dickens. Cross the nation without ever checking into a motel. Cross the nation, stopping at every private museum. Cross the nation solely on gravel roads. Cross the nation without ever looking at a map (or Google).

Thanks to some highway gerrymandering in California in 1964, Route 6 now terminates in Bishop, California, right at the base of the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Too bad for Route 6, but ok by me, because Bishop is the home of the famous Schat’s Bakkery, where I have purchased some of the finest bread of my life. Before 1964, Route 6 terminated at Long Beach, California, and then it was the longest continuous highway in America: Provincetown, Massachusetts, to southern California.

These musings, at the lovely modest RV park on the Cache la Poudre in northern Colorado, made me think about Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) and John Steinbeck (1902-1968) at my assigned picnic table. Did they ever meet? I’ve checked biographies and asked my friends who are experts. The answer appears to be no. Did Kerouac read Steinbeck’s novels? Almost certainly. Did Steinbeck read On the Road? Probably, but not certainly. What would Steinbeck have thought of Kerouac? My guess is that he would have agreed with Truman Capote, who said of On the Road, “That’s not writing, that’s typing.” But we can’t be sure. Steinbeck was a generous reader. What would Kerouac have thought about Steinbeck’s books? I don’t see how you can dedicate your life to adventures on America’s open roads without admiring The Grapes of Wrath, but Steinbeck may have seemed “square” to Kerouac.

Everything I wrote in the preceding paragraph is speculation. We don’t know. Steinbeck was 20 years older than Kerouac. The generational difference could not be more pronounced.

It’s hard to imagine Kerouac driving in a truck camper around the country. And it’s equally hard to imagine Steinbeck hitchhiking the continent.

They may have never met and probably could not find much to enjoy in each other, but they share some important characteristics. They both published their great works in the heart of the 20th century. They both wrote their most famous books fast. Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath in 100 days, in a single tall ledger book. Kerouac wrote the first draft of On the Road in three weeks on a continuous sheet of paper. He said he was hepped up on bennies (methamphetamines), but it was probably just caffeine. They both listened hard to the sounds of actual Americans who did not travel in the same circles as Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson. Steinbeck famously said he did not want his characters to talk like junior college professors. They both used some words the people of America (or their publishers) were not quite ready to see in print and fought to keep their books raw. They both found a way to evoke the romance of the road in America. Kerouac specializes in it. Even the Joads, refugees desperately seeking a better life in California, evoke the freedom of the open road as they scrounge gas, food, and spare tires on Route 66, camping along the side of the route with other Okies. The best chapters in The Grapes of Wrath are road chapters.

Kerouac and Steinbeck both admit that the pot of gold at the end of the road — the fantasy with which we begin our great journeys — usually fails to bring true satisfaction. They both came to feel like literary underdogs, insufficiently appreciated by the critics but beloved by American readers. They both died far too young, Kerouac because he couldn’t stop drinking and Steinbeck because the American medical system was still pretty primitive when he had his health issues in the 50s and 60s. They are both more often read today by young people than by geezers at picnic tables in northern Colorado.

I want to drive the entire length of U.S. 85 or U.S. 101 or Route 66 (what’s left of it) for the same reason I want to ride the trans-Canada railroad or the trans-Siberian railroad or the Orient Express. It is the same reason I want to drive with my anarchist friend Wayne from Denver to Mexico City to recreate the last great journey of Sal and Dean in On the Road. For the same reason I want to run three times around the walls of ancient Troy (northwestern Turkey) on my 70th birthday.

Mostly, I want to get back out on the open road. Kerouac’s sentence is best: “Whither goest thou America in thy shiny car in the night?”

Editor’s Note: Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.