On his way to Sag Harbor, N.Y., Clay travels through Iowa, home to the famous American painter Grant Wood and journalist William L. Shirer.

Iowa — I drove across Iowa this week to get to Illinois and beyond. I’ve been to Iowa many times over the years, but this journey — straight through — was particularly beautiful. It’s spring and it has been raining. The wide farm fields are a deep rich black usually without a single weed anywhere to be seen. All the grass in Iowa in early May — from Kentucky bluegrass to alfalfa and prairie — is spring green, clean, almost garish green. Although Iowa is one of the most productive farm states in America, employing state-of-the-art equipment, including GPS driven tractors, sprayers, and combines, the whole countryside is still punctuated with the old concrete tile silos we associate with the mid-20th century, not the 21st. Over every rural hill I saw old classical gambrel (English style) barns, some painted red, others white, most needing paint and in some degree of dilapidation. One or two had smiley faces, and of course a few anti-Biden signs, some homemade.

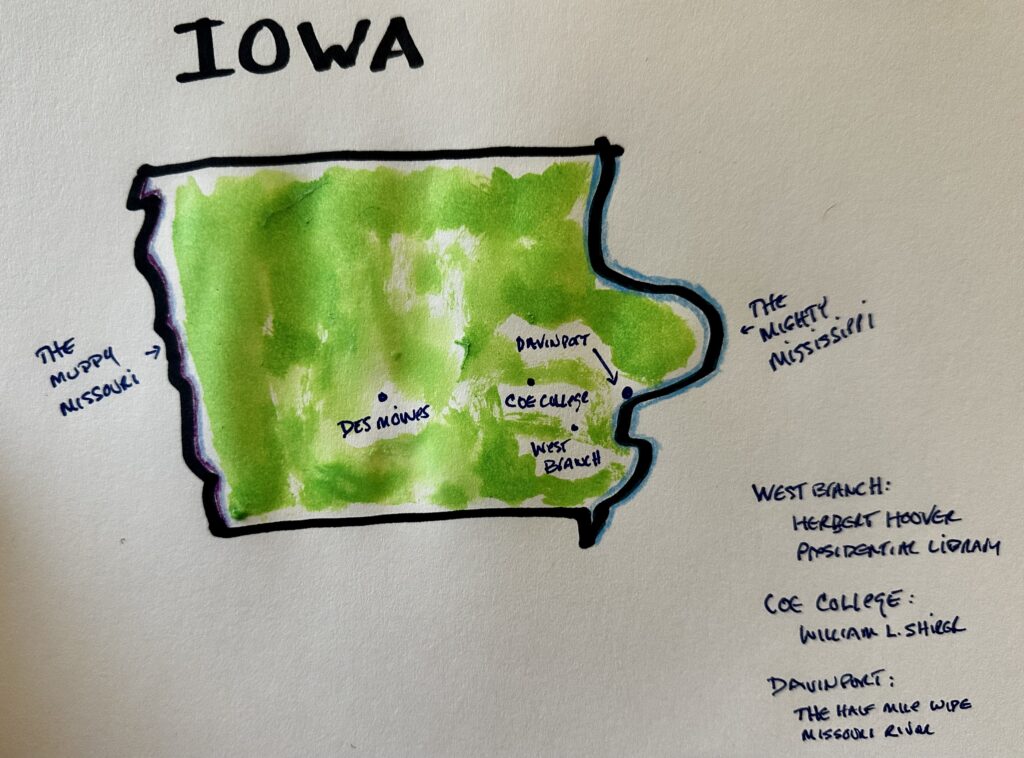

Iowa has the great honor of being bounded on east and west by two of the world’s great rivers. On the west, the Missouri (2,341 miles, beginning at Upper Red Rock Lakes in extreme southwestern Montana; on the east the mighty Mississippi (2,340 miles, beginning at Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota). I know the Missouri River well. I live just two miles from it in Bismarck, North Dakota, and every summer I float the famous White Cliffs section in central Montana on my annual Lewis and Clark cultural tour. (See the Cultural Tours page for details.) But when I came suddenly upon the Mississippi at Davenport, Iowa, yesterday, it took my breath away and I fell into a dreamy Huck Finn meditation. Even this far north the Mississippi is an awesome river, half a mile wide and 30-40 feet deep. If you have not read Twain’s Life on the Mississippi (1883), you owe yourself that pleasure.

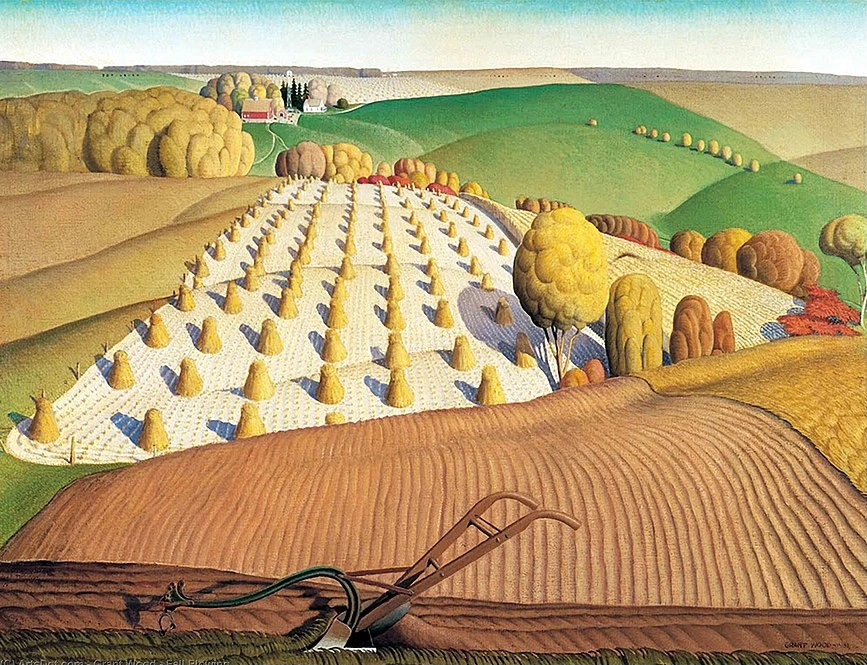

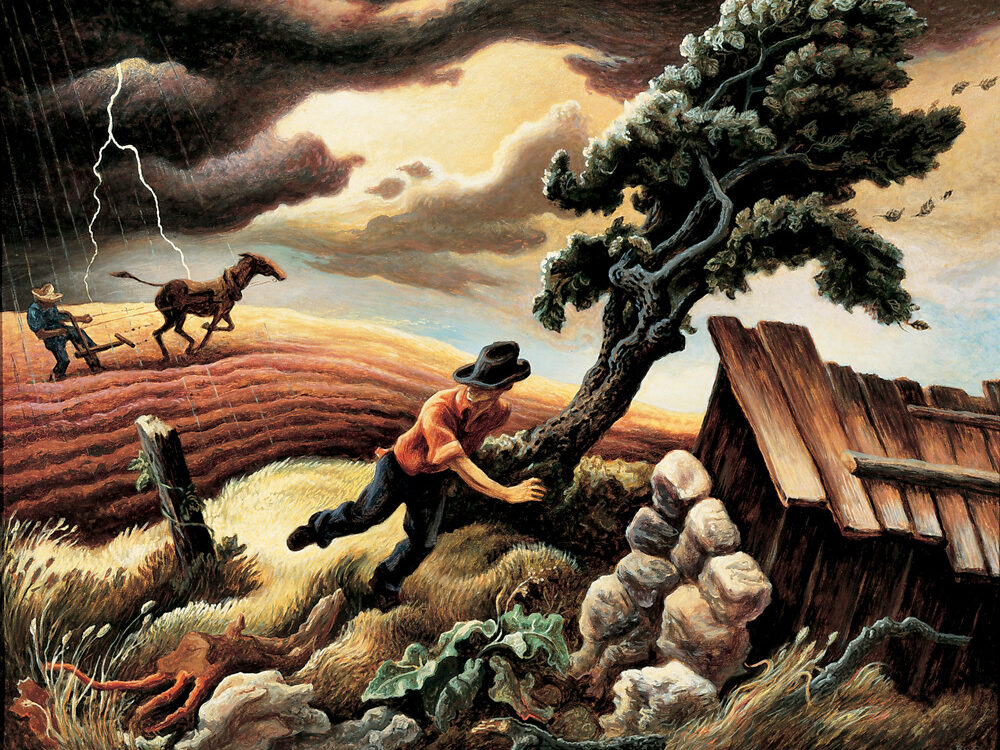

Iowa is not at all flat. Its rolling hills look like they were painted by Missouri’s Thomas Hart Benton or Iowa’s Grant Wood. This gives great character to Iowa’s family farms. Many of the fields embrace hills and gentle ridges, and the farmer has to perform some sinuous plowing on the sides of surprisingly angular hillsides.

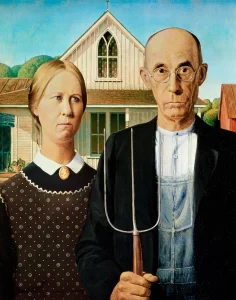

Grant Wood (1891-1942), by the way, grew up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, also the boyhood home of the journalist and historian William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1962), a copy of which John Steinbeck was carrying in his truck camper on the Travels with Charley journey. Everyone knows Wood’s American Gothic (1930). The farm couple were modeled on Wood’s sister Nan Wood Graham and his dentist Dr. Byron McKeeby, neither of whom was pleased with how he depicted them.

But it is Wood’s farm scenes that I was reminded of as I drove Iowa. The state still looks that way.

I’ve been reading about Grant Wood in Shirer’s memoir, American Journey: The Start. Most of his paintings are admiring of rural life and the rural countryside, with a slight edge of irony about what Sinclair Lewis regarded as the psychic claustrophobia of the rural Midwest. The couple in American Gothic do not look happy with their lot.

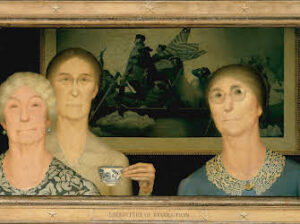

Wood’s most satirical painting is titled Daughters of Revolution (1932). He was commissioned to create a stained glass window at the Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Cedar Rapids. Because he did not regard U.S.-manufactured glass as high enough in quality for his art, he used glass manufactured in Germany for the project. The local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) criticized Wood for using German glass for a World War I memorial. Wood dismissed his critics as “those Tory gals,” and decried “people who are trying to set up an aristocracy of birth in a Republic.” (This, by the way, was Thomas Jefferson’s criticism of the Society of the Cincinnati, which was planned as a hereditary organization for veterans of the Revolution and their descendants. Jefferson saw organizations like this as attempting to create a hereditary aristocracy in an equalitarian republic.) Wood got his revenge five years later. His Daughters of Revolution depicts pretentious and soulless church ladies sipping tea before a framed print of Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 Washington Crossing the Delaware.

I can tell you from personal experience that members of the DAR are still miffed by Wood’s painting to this day!

I’ve chosen a Grant Wood landscape to give you an accurate sense of what I saw on my travels, and two by Thomas Hart Benton.

Over the next few months, Clay will shadow Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and make a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures and subscribe to our newsletter.