If you are a regular reader of Listening to America, you know that for most of 2024, Clay drove some 21,000 miles around the USA, roughly following the route author John Steinbeck traveled for his 1960 classic Travels with Charley. Behind the wheel of his GMC pickup and pulling a 23-foot Airstream, Clay visited 41 states in his own “search for America.” Clay recently sat down with editors at LTA to answer questions and discuss his journey.

What’s the point of driving 21,000-plus miles around America?

I wanted to see America. I’ve been to all 50 states, some of them to dip in and out, sometimes only in airports (which should not count). On July 4, 2026, the United States will observe its 250th birthday. I’m worried about this milestone. If you study the polls, more than two-thirds of Americans say the country is headed in the wrong direction. Of course, they don’t agree on what that wrong direction is. People are disillusioned, cynical, and weary. I heard that sentiment everywhere I went. Some people talked cheerfully enough with me when we were talking about campsites and roads to travel, but they clammed up fast when I tried to start a conversation (even half an hour in) about how America is doing. “We are just so tired of the whole thing. That’s why we are out here, to escape from it all.”

I don’t know if the 250th anniversary will be a celebration, a commemoration, an observance, a culture war cage match, or a wake. I can say honestly that I have never been more concerned about the future of America, and I lived through 1968-1969.

As a humanities scholar who has spent a large portion of his life thinking about the Founding Fathers and particularly my hero, Thomas Jefferson, I have a deep interest in the following questions:

— Where exactly are we?

— How did we arrive at this place?

— Where are we headed as a nation?

— Are things as bad as they sometimes seem?

— What will it take to heal the country, close the breach, and restore a united sense of America?

I read incessantly. In fact, I read every book that pertains to this set of questions in any way. Please let me know if you can think of books I should read. But I wanted to get out and see the country.

I have the capacity to do this. I’m not married. My daughter is grown up and has gone away to fulfill her destiny. I have no 8-5 job. And though I have been enormously privileged — well-educated, well-traveled, well-read, healthy, and blessed with a mobility that virtually no humans have ever enjoyed until now — I take pride that I live in the heartland (North Dakota), away from the centers of power, entertainment, and media. This gives me, I hope, a certain liberation from what we mean by the phrase “American establishment.” I hope that I will discover things worth publishing and sharing and that people will want to know what I see, experience, and learn.

I will keep traveling for the next few years — maybe as many as 10 — and I won’t stop ’til I figure this out, at least for myself.

Where is the United States of America headed?

Why did you choose Steinbeck?

I wanted to tour the country with a purpose rather than just drive around. I was not interested in William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways (though I admire his work). I have a deep romantic attachment to Jack Kerouac, but On the Road is a young person’s book, and I don’t want to hitchhike at my age or at this time in American life.

I’ve loved Steinbeck for decades. It was a simple connect. Steinbeck traveled more than 11,000 miles in a truck camper “in search of America.” I wanted to travel the USA in an Airstream trailer “in search of America” as we approach our national 250th birthday. The Grapes of Wrath is one of our favorite books. I love a road story and I love being a part of my own road story. If I won the lottery (in some respects, I have!) I would drive America about a quarter or half of every year, with no particular destinations, stopping on a dime to take photographs of everything that interests me, turning off into the distance on obscure gravel roads, exploring the country in the loopiest, least focused way.

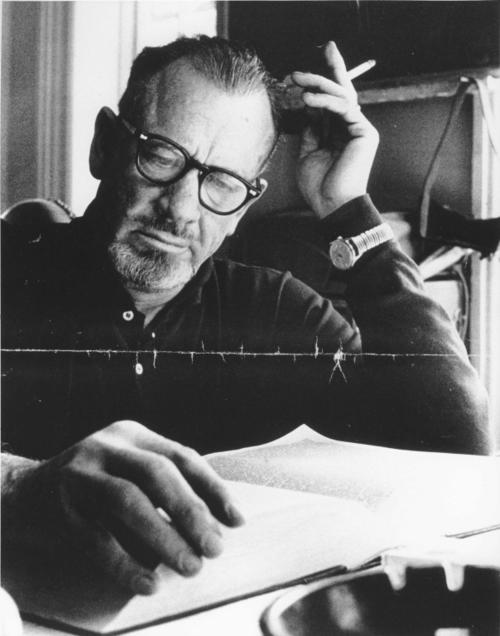

Besides all of that, I have deep respect for the integrity of John Steinbeck. He was much more than a great novelist. He was a thinker, a serious reader, a true intellectual, a man who puzzled over things and told the truth even when it was disagreeable to those around him and even to himself.

It was an honor to follow in his footsteps in his GMC tire tracks.

How high do you rank Travels with Charley?

High. It’s a late book among the several dozen Steinbeck wrote between 1929 and 1968. In many ways, it’s his most light-hearted, personal, and even confessional book. Steinbeck was 58 when he made the great journey, not in good health or vitality. He was trying to prove that he was still the great John Steinbeck who had “always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness.” I don’t think he was any longer that man — nor should one be in the late years — and this proved to be the last incredible American journey of his distinguished life. He did go to Vietnam in 1966-67 and performed heroically there, reporting the war to a home audience, but his big American travels ended when he parked the rig at Sag Harbor in December 1960.

In some respects, the journey itself was, to use terms he would have liked, a failed grail quest in search of America and in search of a more vital Steinbeck. By the time he turned the rig around at Monterey in mid-November 1960, he had largely run out of steam. He confessed that he was overstimulated and did not know how to synthesize what he had learned by driving the country. But if the journey was in some sense a failure, the book he wrote about it was splendid, what my friend the scholar Stephen Beckham calls a gem.

Did Steinbeck keep a journal?

Great question because it raises a larger question about the composition of Travels with Charley. He did not keep a journal. In a long chapter about his day in eastern North Dakota (October 12, 1960) at a roadside stop at the Maple River; he wrote, “I made some notes on a sheet of yellow paper on the nature and quality of being alone. In the normal course of events, these notes would have been lost as notes are, but these particular notes turned up long afterward wrapped around a ketchup bottle and secured with a rubber band.” All he got from those notes were: “Relationship Time to Aloneness” and “Reversion to pleasure-pain basis.”

That’s it! Steinbeck wrote Travels with Charley months after his return to New York. In fact, he wrote most of it in the Caribbean, where he and his wife Elaine spent part of the winter of 1960-61. He recollected places, viewsheds, incidents, encounters, and even conversations — long after they occurred. Wordsworth spoke of experiences “recollected in tranquility.” This was certainly how Steinbeck wrote the book at St. James, Barbados, 2,100 miles from Long Island, New York.

Fortunately, he wrote several invaluable letters to Elaine during the course of the journey. These have been of great help to biographers and those trying to figure out the exact movements of Steinbeck during this journey.

If he wrote Travels with Charley without the help of a journal or significant notes (but surely with his letters to Elaine by his side), it is inevitable that Steinbeck had to construct the book from memory; that he almost certainly garbled or enhanced the conversations he had along the way; that he may have been occasionally confused about the exact sequence of events and encounters. In short, he had to use the resources of his great talent as a novelist and reporter to reconstruct the journey. There is a very slight disillusioning effect when you first realize that he employed the tools of creative nonfiction to write what appears to be a faithful account of his travels. But you soon shrug your shoulders, realizing that this is how virtually all such books are constructed and that Steinbeck never intended this book to be some sort of “transcript” of his journey.

Why didn’t you take a dog?

Well, first, I don’t have a dog. I love dogs and I would have enjoyed the companionship. I know, too, that a dog is a great “ambassador” and conversation starter. I would have had scores more encounters with people along the way had I traveled with a giant French poodle, or even a miniature Schnauzer, for that matter.

Why, then?

A dog is a serious responsibility. My Steinbeck journey lasted 210 days. Then what? I travel about 150 days yearly, even when not chasing America in an Airstream. I live alone. It would be unfair to have a dog under such circumstances. This coming year, I will be retracing the Lewis and Clark expedition from Monticello in Virginia to Astoria, Oregon, in the Airstream. I suppose I could have purchased (rented) a Newfoundland that would “pass” on the Steinbeck trip and “star” on the Lewis and Clark trip, but that’s a lot of dog, and then, afterward, I’d have a Newfoundland to place with friends or dog-sitters when I travel on other business.

At least six people gave me stuffed dogs to take with me. It’s not quite the same! No roadside conversation began with, “Hey, good looking stuffed dog on your dashboard.” Two people offered to lend me their dogs, but I have a terrible memory of a cat bursting out of my car long ago on a busy intersection in Denver and making a run for the Yukon. We rescued the damn cat, but not without some frantic dashing across busy traffic lanes. Calling a good friend to say, “Your dog will not be returning with me,” was more than I was willing to risk.

Did you have any rig breakdowns?

Three. First, near Athens, Ohio, my twin batteries caught fire and melted down 100%. At that point, the Airstream was as stricken as Apollo XIII. And I had no Houston to radio in the problem. Fortunately, I was only a handful of miles from the national Airstream Repair Center at Jackson Lake, Ohio! It was Memorial Day weekend, and they were swamped, but they found a way to work me in as quickly as possible, honored a warranty that had just lapsed, repaired a few other things as long as they were at it, and got me back on the road with splendid new batteries. That fire could easily have ended the journey.

Second, my friend Loren P. burned out some systems when he plugged them into the wrong power box at his farm on the Olympic Peninsula. It was an entirely innocent incident, the damage was slight, and he had the skill set and the tools to fix the problem while I was away on my annual summer Lewis and Clark tour in Montana. While examining the trailer’s undercarriage, he noticed that several of my tires were badly worn. To assuage his pyromaniacal guilt, he made an appointment for me to get four new tires when I returned. I paid for them, of course, but I was immensely grateful that he saw the problem before I had a flat or blown tire by the side of the road. Steinbeck had to replace a pickup tire somewhere in Oregon. He prided himself (as I do not) for his capacity with tools and repair projects, but he was soaked through by the time he succeeded, after which he hastened to a tire shop to get the kind of heavy-duty tires that could bear the considerable load he was carrying — books, tools, firearms, clothing, writing materials, and enough alcohol to host a tailgate party.

Third, a quaint, covered wooden bridge in Vermont sheared off my Airstream awning structure. See “low point” below.

Is Steinbeck your favorite author?

No. These lists are inherently problematic, but I’d say my favorite authors are Charles Dickens, Shakespeare, John Donne, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain, James Boswell, and George Orwell — something like that. But Steinbeck ranks very high in my mind.

I do believe The Grapes of Wrath is one of America’s top 10 novels, maybe even the top five. I read it at least once every couple of years. I love Of Mice and Men and Cannery Row, and once every five or six years, I make a run at East of Eden. I also greatly admire Steinbeck’s book about visiting the U.S.S.R. with his photographer friend Robert Capa.

Does Steinbeck’s truck camper still exist?

Yes, amazingly. It’s now the great treasure of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California. When Steinbeck returned to New York after his long 1960 journey, he promptly sold the truck and the specially manufactured “cabin” he had commissioned to sit in its bed.

It was purchased by a local farmer who used the pickup for a while but stored the camper unit in his barn. There is sat for a very long time. We are fortunate that it was not taken to a landfill. The farmer brought it to the attention of the Steinbeck community. It was purchased, along with the pickup, and transported to Steinbeck’s old stomping grounds in Monterey Bay, California.

It arrived in Salinas in 1990. A local body shop owner named Gene Cochetti restored it inside and out.

The Steinbeck Center has excellent interpretive exhibits and a perfect gift shop and bookstore. But when I go there, I get myself to the Plexiglas-protected display of the pickup and camper cabin as quickly as possible. You can peer in to see the walnut walls, the chemical toilet, the table at the front end that can be turned down to make a bed, the miniature kitchen, and a replica of the lantern he bought in Stonington, Massachusetts.

Because of the work I do, my association with the excellent staff of the Steinbeck Center, and having begged 42,000 times to get into the camper “someday in the future,” when I gave a speech there two years ago, the staff surprised me — no doubt their judgment was impaired by the splendid meal and its … er, accoutrements, that they pulled down the Plexiglas barrier and gave me a few minutes inside. It was one of the great joys of my life.

What was the high point of the journey?

There are too many to count. At least two dozen times, when I had settled in at a campsite for the night, tidied up inside (hard to keep things battened down on some of America’s roads), and then took a stroll to check out my surroundings, I found myself saying, out loud, to nobody — to the universe — “I am the luckiest man alive, I am so very fortunate, I am so very glad to be alive this evening.” The journey was much more satisfying than I had imagined, and my imagination had been big.

To name a few. … Walking in the immense silence of the redwoods in Northern California. Sitting in the borrow ditch on Route 66 in Arizona, reading a key passage from The Grapes of Wrath. Crossing the Mississippi River (below Minnesota) for the first time in many years. Hiking to the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers with my friends Dennis McKenna and Dr. Susan Ryan in Canyonlands National Park. Letting gigantic Texas have its way with me for a whole week.

But maybe the highlight of highlights was when I took the time to visit Acoma Pueblo about 60 miles west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Sky City Pueblo there was established in the 11th century (more than a thousand years ago). The Pueblo sits on a 365-foot mesa. Today, it is lightly inhabited but remains an important cultural center. I had heard about it and read about it, but when our trusty scout Frank Lister suggested that I not pass it without taking the time to visit, I felt it was almost an act of grace calling me there. Individuals of the Acoma Pueblo tribe guide the tours. It was a stunning, unforgettable, humbling, and even spiritual experience. I have a close friend, an archaeologist, who has a relationship with the people and the community. She has invited me to visit Acoma during their annual St. Stephen festival.

So when I go out looking for America, it is essential to remember that I mean “the United States of America,” that upstart nation born more than 750 years after Acoma was a thriving hightop community in the Southwest. One of the primary impulses of my life now is to try to see America through the lens of Indigenous people, their communities, their landscapes, their history, their continuing struggles, and for what they have to teach us bewildered Anglos.

I’ll be back.

What was the lowest moment of the journey?

It came early. I was in Middlebury, Vermont, to interview the eminent Steinbeck biographer Jay Parini. He carefully directed me to the restored farmhouse they live in a few miles from Middlebury University. I was only one week into my five-month journey, and the Airstream was brand new. Jay did not warn me about the romantic covered bridge I would have to drive through to get to his home. About two-thirds of the way through the bridge, the lane narrowed. I slowed to a crawl. As I inched forward, one of the bridge struts clipped the awning on the right side of the trailer and wrenched it entirely off. My heart sank. I stopped when I could, walked back to pick up the pieces, and fell into a deep gloom. For a while I thought I might be able to fix it, but that proved illusory. Eventually, I had it replaced at the cost of $1,775.

It was a minor accident. But you know how you feel when you get some sparkling new vehicle, and you are paranoid about dinging it in any way. But you know, too, that once the first ding or dimple has happened, you learn to relax and then everything gets smoother.

Were you ever lonely?

No. Not once. I missed a few people, at times acutely, but I never felt lonely in any place at any time. I know this sounds nerdy, but a person with a book (or an iPad), a notebook, a smartphone, and a laptop must work hard to be lonely. My iPad has approximately 250 books on it, from Milton’s Paradise Lost to the essays of Christopher Hitchens to Dickens’ Bleak House. I camped in some of the most beautiful places in America. How can you be lonely if you wake up under the shadow of Devils Tower?

What would you do differently if you could start the journey over again?

Really, not much. It would be quite a bit different to start in the autumn rather than the spring. Steinbeck’s journey had a lovely autumnal feel to it. To have begun as the first frost was imminent, when all the children were back in school when the leaves were turning, might have brought its own delights. But that is a small matter.

Mostly, I would just slow things down. I traveled twice as slowly as Steinbeck, but it was still too fast. I averaged about 200 miles a day. I seldom stayed in one campsite for more than one night. It’s hard to meet people when you move that fast. I needed more time to read and more time to write. More time to sit in a camp chair gazing at the landscape.

Did you have any encounters with the law?

Amazingly, not once. I fully expected to get a few parking tickets, hauling a 23-foot trailer, and even anticipated a few moving violations or California encounters with stop signs. But not once in 21,000 miles did I trip that sometimes sensitive wire. Because I was hauling a trailer, I never drove more than 65 miles per hour, often less. I ambled America. I tried to be a very responsible driver in that I pulled over, often under challenging circumstances, to let the cars and trucks behind me continue their journey at their own preferred pace. I do believe that I owe the New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois Departments of Transportation for some toll road violations because today, the kiosks are often uninhabited, and my rig was not equipped with an ETC device. I fully expect to be swarmed by SWAT teams as I pass through greater Chicago next summer!

Where’s your Airstream now?

It’s in storage near Salisbury, North Carolina, at an RV and boat storage facility. I saw no reason to haul it back to North Dakota for the winter since I will begin the 2025 journey at Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia. My friend Russ Eagle found a facility. I parked it there just before Thanksgiving and then high-tailed it with my GMC pickup to Bismarck, where I entertained two good friends for my favorite national holiday.

I nearly destroyed the Airstream before I backed into its narrow and torturous storage bay. As I was trying to figure out just where to turn into the storage facility, a cement truck came hurtling over the hill right in front of me, and it must be regarded as some secular miracle that a: I was not killed right there b: the Airstream was not crumpled like a piece of generic tin foil, and c: my friend Russ, who was in the passenger seat, did not file a restraining order to avoid ever getting in a vehicle with me again.

I take full responsibility for what happened, and yet — in some sense — it was just one of those things. The cement truck was going way too fast. It was a blind hill and a very narrow road. I’m no physicist, but I know that the cement truck wins every time in the game rock, paper, scissors, or Russ, Airstream, and cement truck.

You couldn’t do this alone. Who helped you along the way?

In addition to the kindness of strangers, I am just the public face of a great team. My friend and partner Dennis McKenna is the Producer, Director, and Editor in Chief. Raina Hall of Los Angeles copy edits, formats, handles the podcast logistics, keeps the videos in the queue, and manages the website LTAmerica.org. Frank Lister of Escalante, Utah, is my intrepid scout. Nolan Johnson of Bismarck, North Dakota, is my young friend, videographer, and editor of the weekly podcast. Russ and Liz Eagle manage the workflow logistics, and Russ — as a significant Steinbeck scholar — was essential to my journey and satisfaction.

What did you learn?

— I learned that Steinbeck is right: this is a “monster country” in the sense of its monstrous size. I drove 21,400 miles, visited 41 states, and spent more than 200 days on the road. America is immense. It is also very lightly populated. According to the 2020 census, 80% of Americans live in cities and just 19% in rural areas. As Gertrude Stein wrote, “In the United States, there is more space where nobody is than where anybody is. This is what makes America what it is.” I love the open road. I love driving America, especially the American West, more than just about anything I do.

— I learned that America is an astonishingly beautiful country. From the forests of Maine and the quaint, tidy, “English-derived” villages of New England to the wide open endlessness of Montana; from the immense privilege of Long Island to the windswept marginality of Great Plains towns; from the immensity of the Great Lakes to the tiny prairie potholes of North Dakota; from the appalling corn monoculture of Indiana and Iowa to the sparse, stark red sandstone deserts of the Four Corners area; from the burbling mountain streams of Idaho to the burst-into-tears magnitude of the great Mississippi River; from the gray East Coast Atlantic to the sparkling Pacific at Point Lobos on the Monterey Peninsula. … Unlike Steinbeck, I visited as many National Parks as presented themselves along my route, but he is right that they are outliers. I’m extolling the magnificence and often the sublimity of the regular old landscapes of America. No day passed without a moment when America took my breath away.

— I think of myself as an American patriot. Always have. And I hate that the Far Right sometimes claims patriotism as its own patent. But on this trip, I fell in love with America again … and again … and again.

— I learned that most Americans, at least most of the Americans I met on my journey, are just good and decent people going about the business of life. Civil, generous, friendly, law-abiding, modest. I met hundreds of people along the way. Only two were angry Americans who wanted to shout down any view of the country that does not precisely conform to their own.

— Perhaps most of all, I learned that our national cable news and commentary channels do us no service. They hype and distort the situation, ratchet it up rather than ratchet it down. These partisan echo chambers essentially urge us to demonize the opposition, whatever it is, to “other” people who do not share our traditions, our heritage, our language, and our political outlook. I’m old enough to remember the golden age of CBS News, of Walter Cronkite and my hero Eric Sevareid, and NBC’s John Chancellor and ABC’s Peter Jennings. Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite would be embarrassed by the wholesale abandonment of any pretense of objectivity and fairness in today’s cable media.

My Airstream has a modest television monitor and a DVD player over the bed. I never turned it on, even during presidential debates or the World Series. I knew that if I ever turned it on, even once, it would be a slippery slope and I would soon be binge-watching episodes of Green Acres.

What next?

In four months, I will fetch my Airstream out of its winter storage, get it road-ready, and head from North Carolina to Charlottesville, Virginia, to begin my great Lewis and Clark journey at the home of America’s Da Vinci, Thomas Jefferson. I cannot wait. I know much more about Lewis and Clark than about Steinbeck. I edit the Lewis and Clark quarterly, We Proceeded On, which will feature reports of my travels. I have written three books and two chapbooks on Lewis and Clark, including what I take to be my major work of scholarship, The Character of Meriwether Lewis: Explorer in the Wilderness. I’ve canoed sections of the trail, flown in Cessna planes over the Montana and North Dakota segments, flown in a helicopter over the White Cliffs in Montana, ridden horseback in the Bitterroot Mountains on the Lolo (Nez Perce) Trail, and drove the trail three times between St. Louis and Astoria, Oregon. But I have never driven the entire trail, as Stephen Ambrose liked to put it, “from Sea to Shining Sea.”

I’m tan, rested, and ready. Well, actually, I’m pale, too sedentary, and only partly rested. But I am so ready. I plan to depart from Monticello on or about May 5, 2025. Stay tuned!

Editors Note: You can read all of Clay’s dispatches and reports and watch videos from his 2024 Travels with Charley adventure here.